Search Wild Foods Home Garden & Nature's Restaurant Websites:

Viburnums: Nannyberry, Highbush Cranberries & Others

Contents On This Page:

- Highbush Cranberry

- Nannyberry

- Hobblebush

- Squashberry

- Possumhaw

- Northern Wild Raisin

- Blackhaw

- Rusty Blackhaw

Highbush Cranberry (Viburnum trilobum) I found on the edge of a woods in the city.

(NOTE: If you are not interested in growing Viburnums, but just finding the fruit and using it, try going to the Nature's Restaurant Online site Viburnums page.)

Viburnum. This is a very interesting group of shrubs and small trees. The fruit can range from absolutely awful to very good depending on which one. They can be difficult to distinguish one from another. Sometimes, it is impossible to know (in my opinion) until you try the fruit. Even taxonomists can't agree in some cases if there are two distinct species or there are just variations of one.

There are some characteristics that all Viburnums share. The leaves are opposite on the twigs, and the twigs are opposite on the branches. The flowers come in clusters, and are usually white, off-white to pinkish. The fruit comes in clusters. The fruit are a drupe and have a pit with a single seed. Often that pit is oval shaped and flattened. Very often there is a scent to the flowers - sometimes nice, sometimes not. There is one other common characteristic that most of them share - they are generally a very beautiful shrub or tree any time of the year with the flowers in the spring, colorful fruit and rich fall colors. Even in winter the branching they take is more often than not very interesting and nice looking.

Many varieties are available at nurseries, but be careful - it sadly is the case they are often mislabelled - a side effect of them being hard to tell one from the other, and since most people don't eat the fruit, it doesn't matter to them. Very often the horrid tasting Viburnum opulus is sold as the nice tasting, identical looking Viburnum trilobum, and this is made even more complicated by the fact those two can hybridize. When you plant Viburnums, plant more than one to help with pollination to give a good crop - if you plant just one, you may get very little fruit.

Seeds: If you start by seed, they usually take two years for the seed to germinate after planting.

Cuttings: Most of them take very well from cuttings made in the spring or summer stuck in the ground, just keep them wet until the root system takes. If you take cuttings from one tree, remember that the trees the cuttings turn into are genetically identical clones of the tree you took the cuttings from, so they won't cross pollinate - they are the same tree in two or more places. Therefore, try to get cuttings from different trees spread apart a good distance. If they are really close, they could be clonal colony trees that spread by root, so again, they would be clones.

To grow from cuttings, there are three basic methods that are workable for the home grower. The first and simplest is to literally just push a cutting into the ground. Second is to start the cuttings in pots with soil. Third is to put them in water until they root and transplant. I'll cover all three, but the first thing you need is to get the cuttings.

- Get your cuttings in the Spring after the buds have opened.

- Take about 15 cm (6 inches) of the end of a branch. Should be woody where you cut.

- Cut just below where a pair of leaves come out so that there is about 6 mm (1/4 inch) below the lowest leaf pair.

- After cutting, immediately put in a plastic container with room temperature water that is clean and not too high in chlorine.

- Take about double the number of cuttings you will want to plant - some won't root.

- Just moments before you are going to plant or put in water, pull off the leaves from the lower part of the twig - you want to plant about 2/3 of the twig and leave about 1/3 above the soil, so pull off whatever will be below the soil. You must leave at least one set of leaves at the top end.

- Put some rooting hormone (helps the process but not absolutely necessary) on the part of the twig that will be under the soil or water. If dabbing on the rooting hormone, the part you want it on is where the leaves were that you pulled off. Follow the instructions on the label for the rooting hormone. There are powders and liquids. When you go to buy the hormone, if you buy at a garden center, you can ask for which one by telling them it is for hardwood. If at a hardware store and they don't have expert gardeners there, read the labels, and buy the one for hardwood cuttings.

If you are going to put in a glass of water to sprout the roots, slowly lower the cutting into the water trying not to wash off the hormone. Change the water every few days so it doesn't go off. Put in a very light, but not direct sun spot. If you live where the air is dry, you can put a small plastic bag over it all held with an elastic, and a couple of pencil sized holes in the plastic. Try not to let the plastic touch the twig or leaves. If the air is humid, you don't need to cover. It can take a while, but most should root. When roots are about 2.5-5 cm (1-2 inches) carefully transplant into a pot, or into the garden and keep moist.

If you are going to start the cuttings in soil in pots, 10 cm (4 inch) pots should be about right. Fill with sterilized soil, peat moss and sand or peat moss, sand and Perlite (1/3 of each). I have started many, many plants by cuttings over the years, and find the Perlite does help. It is available at garden stores in small to large bags. Make sure before you place the cuttings in the soil medium that it is full wetted and drained. If there is peat moss, this can take a few minutes. Where the cutting is to go, poke a hole in the center of the soil in the pot, this stops the soil from rubbing the rooting hormone off the twig when you push it into the soil. Put a pencil beside the cutting, put you finger nail on the pencil to measure the length of the part of the cutting that is to be planted, and make the hole in the soil the same depth. After the twig has the hormone on it, put it into the hole, touching the bottom of the hole, and work the soil firmly to make full contact with the sides of the base of the twig. Put a plastic bag over the whole thing, secured with a rubber band around the pot. There should be one or two pencil sized holes in the bag. Put in bright light, but not direct sun. If you can work it, have it so the sun gets on the pot, or the pot stays warm - this can make the twig root faster. Make sure the soil stays damp all the time. When you see little white roots coming outside the bottom holes of the pot, transplant into the ground.

The final way of doing this is to do basically the same thing as with the pot of soil, but just in the ground. If the ground is very damp, and there isn't direct sunlight, you can just poke a hole in the ground, put in the twig and firm the soil around the twig base. I've done this with and without rooting hormone, and find both work, but with hormone is a little more reliable. If the area is sunny, put something over it like a chair to stop it from getting the direct sun. You could also put clear plastic containers over it to keep the humidity in. I've found in some conditions it helps, in others it just promotes rot - it's a judgement call. There are plastic domes you can buy that are make to protect young plants from frost, but I've always just used clear empty bulk food nut containers. Once you see the twig starting to grow new growth, you know it took and can uncover and slowly get it used to more sun, by first exposing it morning and evenings and all day on cloudy days. A couple of weeks of doing this, and it should be fine left uncovered. Keep damp for at least the first season.

Soil & Site: These are one of the best shrubs/trees for gardens if you have the right conditions, and there is a Viburnum for just about anywhere. Most like damp, well drained soils and partial shade, but check the habitats and soil pH in the descriptions for the different Viburnums. If you buy one at a nursery, they will tell you what conditions it will need.

Maintenance: They tend to keep a nice shape without a lot of pruning. Mulch and some fertilizer each year will help, but they don't need a lot. For the more acidic soil loving varieties, leaf and conifer needle compost is perfect. For the couple that like neutral to slightly alkaline conditions, deciduous tree leaf compost, or composted manure spread around under the tree with some mulch over top is adequate.

Harvesting: When ripe in the fall, gather the clusters of fruit by gently cutting off the whole cluster and placing in a cardboard box to take home. On many, the fruit is best when it starts to shrivel up a little first.

Using: Most sources that provide recipes for any Viburnum fruit for making jams or jellies, or the paste for adding to meals talk about cooking the fruit, then separating the seeds and skin by putting the cooked fruit through a food mill or pushing through a sieve. You might find the odd source saying to remove the seeds first, before cooking. I don't know if it really matters, but since the seeds are bitter, I personally remove the seeds first. Yes, it is a bit more work, but not a lot. There are three ways I've tried, choose one you like: One way is to put all you have collected in the freezer and leave for a day, then take them out and let them thaw. They go mushy after that, and just run them though a food mill, take the seeds that are left over, put them in a container with some water, rub them around with clean hands, and put that through a sieve. After that, cook. Another way is put the fresh fruit in a pot, mash with a potato masher, then put it through a food mill, put the seeds in a container with water, rub around and sieve. There is a third way. Boil them in just enough water to cover them for 5 minutes, run though a food mill, put the seeds left over in a container with some water, rub around, sieve, put it all together, and cook for remaining 15 minutes or so, or until it has boiled down to the thickness you want. It will thicken more when fully cooled. Two more notes: if they are the type of Viburnum fruit that is best collected when shrivelled up a bit, soak in water to rehydrate before any of the above procedures & make sure all bits of stem are removed.

Below are the most commonly found Viburnums in Eastern North America:

Highbush Cranberry

Highbush Cranberry (Viburnum trilobum), sometimes the name is listed as "Viburnum opulus var. americanum". Also known as Kalyna and American Cranberrybush, Cranberry Tree, Crampbark Tree, Guelder-Rose, Wild Gueldes-Rose, Gueldres-Rose, Cherry-Wood, Rose Elder, Red Elder, Marsh Elder, Water Elder, White Elder, Gadrise, Gaiter Tree, Gatten, Love Rose, May Rose, Pincushion Tree, Dog Rowan Tree, Whitten Tree, Squaw Bush, Witch-Hobble, Witchhopple.

Although not related to other Cranberry species - it is a Cranberry in name only - the Highbush Cranberry is good in its own right, and can be used and eaten the same way as true Cranberries. It is a shrub that in no way resembles the other Cranberries which are in the Vaccinium genus. The Highbush Cranberry can grow over 3 meters (10 feet) tall (although usually found shorter), has leaves that are similar in appearance to Maple leaves (but with three lobes) and has clusters of white, five petalled flowers. Look for it in damp, shady areas that do not dry out, but have a good loamy soil. Unusual for a Viburnum, it does not like acid soils, so if you live where there are alkaline soils and limestone outcroppings, this bush should be around along creeks and low areas near rivers and would be a good choice to grow at home. By the way, there is the native Viburnum trilobum and the common Viburnum opulus that has naturalized in North America. Hard to tell apart from looking at them, but if you compare the leaves carefully in the pictures below, you can see how each leaf on the native (and edible) Highbush Cranberry (Viburnum trilobum) has more exaggerated lobes. The fruit is virtually identical.

The native Highbush Cranberry (Viburnum trilobum) is the good one - tart to mild tasting, like a Cranberry overall, but not as sharp. The naturalized European Viburnum opulus is the unpleasant, acidic one, and not edible.

A good tree for the fruit and a very nice ornamental. Just make sure you plant the Viburnum trilobum and not the Viburnum opulus. Seems from my experience, nurseries sell the wrong one, and often mislabelled. If you go this route, question them whether they have tasted the fruit. Tell them it is important this is not the Viburnum opulus or a hybrid with it. Otherwise, best to either transplant a little one near a bigger one where you have confirmed the berries taste good, take cuttings from a good tasting one, or plant a seed and be patient - they will take over a year to sprout, but will then take quickly if the conditions are good for it.

This one can also easily be mistaken for the Viburnum edule. So, how do you tell the difference? The most reliable way is by where you find it. If you are in a northern boreal forest, and find one in a damp area, it is most likely the Squashberry - the Viburnum edule. If you are where the dominant forests around are not boreal, and the soil is more likely alkaline and the ground where it is growing is not wet/damp (but could be near water), then most likely it is the Viburnum trilobum. Either one is good for growing at home, just get the one that matches the conditions you have.

Smaller branches come off larger ones in opposite pairs like the leaves. The branches are long and thin with little taper, and bend over in an arch with the weight of the leaves. There are a lot of branches creating a very thick mass of branches and leaves.

The red berry (technically a drupe) is round/oblong with one flat seed. The berries are on clusters, and if you look closely, you will see that the stems also divide in opposite pairs. Fruit is green when unripe. The fruit can be eaten raw, but it is best cooked into jams, jellies, etc. - it doesn't smell very good raw. When cooking, add some orange or lemon peel, and this will help get rid of the unusual smell of the berry. Pick in fall (September to October) after it turns red, but still a bit hard for jams and jellies. It has a fairly high natural pectin content, so take that into account when preparing. After a frost or freezing, it goes mushy.

Description:

- USDA Plant Hardiness Zone: 2-7 (More information on hardiness zones).

- Soil pH: 6.6-7.5

- Plant Size: Up to 3 meters (10 feet) tall or more on occasion

- Duration: Perennial Shrub or small tree

- Leaf Shape: Variable from Maple leaf like with three lobes to Ovate

- Leaf Phyllotaxis (Arrangement) on branch: Opposite pairs of leaves on branch - at the end of a branch is a terminating pair

- Leaf Size: 6-12 cm (2 1/3 to 4 3/4 inches) long 5-10 cm (2 to 4 inches) wide.

- Leaf Margin: Variable from Serrated (saw toothed edge) on some leaves, some appear fairly smooth with the occasional sawtooth

- Leaf Notes: Leaf stems are red to brownish red, except right near the base of the leaf where they are green. The leaves are dark green to a yellowish tone to the green color. In the fall they turn a maroon red, purplish red and one variety turns yellow to red.

- Flowers: Clusters of white, five petalled flowers

- Fruit: 12-15 mm (1/2 to 5/8 inch) diameter, bright red, green when unripe

- Bark: The bark on mature trunks or branches is grey with hints of red here and there with spots, bumps and scales. New growth twigs are the same red (brownish red) as the leaf stems.

- Habitat: Where there is good, moist but well drained soil by creeks and rivers with some shading in soils that are neutral to alkaline - does not like acidic soils like true Cranberries.

Web Resources:

- Recipe search on the web here (Google search) and here (Bing search).

- Pictures on the web here (Google images) and here (Bing images).

- Interactive USDA distribution map and plant profile here.

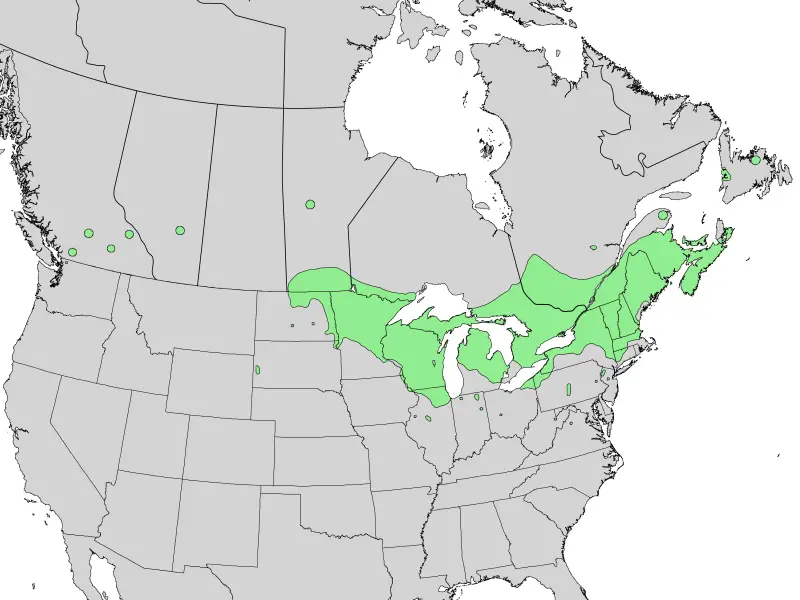

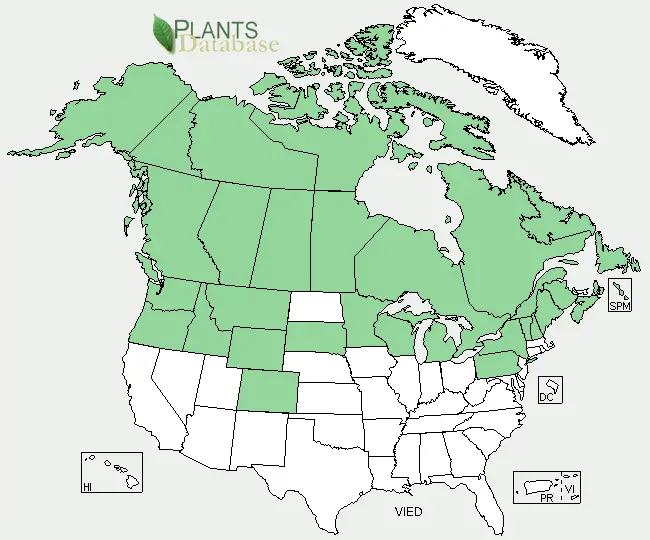

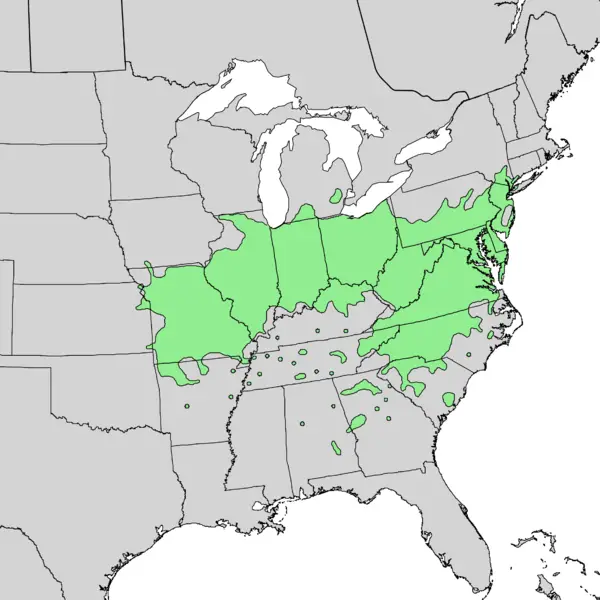

Highbush Cranberry (Viburnum trilobum) range. Distribution map courtesy of the USGS Geosciences and Environmental Change Science Center, originally from "Atlas of United States Trees" by Elbert L. Little, Jr. .

Highbush Cranberry (Viburnum trilobum) seeds. (Steve Hurst, hosted by the USDA-NRCS PLANTS Database)

Highbush Cranberry (Viburnum trilobum) leaf. Compare to the Viburnum opulus leaves in the pictures below.

Highbush Cranberry (Viburnum trilobum) flowers and leaves. (USDA-NRCS PLANTS Database / Herman, D.E., et al. 1996. North Dakota tree handbook. USDA NRCS ND State Soil Conservation Committee; NDSU Extension and Western Area Power Administration, Bismarck)

Highbush Cranberry (Viburnum trilobum) leaf stem attachement and next year's buds forming. Picture taken in late September.

This is the not edible Viburnum opulus - compare to the edible Viburnum trilobum above. Leaves are opposite on the Viburnum trilobum and Viburnum opulus. At the end of branches there are two leaves.

Though these are not edible Viburnum opulus berries, the Viburnum trilobum look identical. Taken in early November.

Nannyberry

Nannyberry (Viburnum lentago). Known also as the Sheepberry and Sweet Viburnum. This is a bush to a small tree found in damp areas on the edges of woods, or in woods that are not too dark.

Although often seen as bush sized with many little trunks coming from the same spot, it can be a single tree with a truck up to 25 cm (10 inches) diameter. This is one of those plants that can form what are known as clonal colonies, that is, a single tree will send up shoots from the roots and there will be many trees genetically identical in a single area. Often, this forms what looks like a dome of trees. Twigs are opposite on branches, and leaves opposite on twigs. In the fall, when looking for the berries, one distinguishing feature of this tree is that next years flower buds, which are on the ends of the branches, look like a bird's head with a long beak. The twigs produce an odd, not pleasant smell when crushed.

A very good choice to grow. A very beautiful tree/shrub at any time of year, the flowers are very nice, the fall leaf color is excellent, the shape of it is nice, and it is compact overall. It will spread by the roots, but if planted in a grass area that is mowed, it is not a problem. You can buy cultivars of this, and plant by seed. Keep in mind Viburnum's seeds sit dormant for a year, so don't be disappointed if it doesn't sprout the year after you plant the seed. If you find one in the wild, there should a few young ones around it. Transplant in the fall after the leaves have fallen, or the spring after the ground thaws. Keep the soil around it wet the next summer where you planted it, it should take well. Cuttings will work too.

There is a single seed in each berry that takes up most of the berry. It is watermelon seed shaped - flat and oval to almost round. The seed can be tan-brown to black. The berries hang in clusters on the ends of branches. The berry is ready to eat in the fall when the leaves start to turn color - usually red, but sometimes with a purple hue. The berry has a thick raisin like texture that tastes a little like raisins as well. It is at the perfect ripeness when slightly shrivelled - again, similar to a raisin. It is a very sweet, tasty berry, though there isn't much to eat in each one due to the seed size. One feature is the stems of the berry clusters are bright red.

The berry can be eaten fresh off the tree, or cooked to make a paste like jam that is good on toast and crackers. To make the paste, gather a lot of berries, simmer for a about 45 minutes with water. Then you need to separate the jam from the seeds. A food mill is perfect, but you can work the jam through a sieve leaving the seeds behind. If you do it this way, use more water to cook with, so the mix you push through the sieve is thinner, then when the seeds are separated, you can simmer it down thicker again. It will thicken more when cooled, so take that into account. Keep in fridge.

Description:

- USDA Plant Hardiness Zone: 3-7 (More information on hardiness zones).

- Soil pH: 5.0-7.5 (ideal is 6.0-6.5)

- Plant Size: Up to 9 meters (30 feet) high

- Duration: Perennial Shrub to small tree

- Leaf Shape: Simple (not compound), Ovate to round

- Leaf Phyllotaxis (Arrangement) on branch: Opposite

- Leaf Size: The leaf can be 5-12.5 cm (2 to 5 inches) long, but 7.5 cm (3 inches) is most common.

- Leaf Margin: Very small, sharp Serrated (saw toothed edge) and a pointed tip.

- Leaf Notes: The color of the leaf is a yellowish green on the topside, and little brown dots on the underside. The stem of the leaf has edges on each side giving it a trough shape.

- Flowers: The flowers come out in the spring, they form white clusters of very small flowers at the ends of the branches. Sweet smelling. This distinguishes it from the unpleasant smelling flowers of the Northern Wild Raisin (Viburnum cassinoides) which is otherwise very similar.

- Fruit: The berry is between 8-13 mm (1/3 to 1/2 inch) long, blue-black or purple black in color, and oval shaped - longer than the diameter. Berries hang in clusters on the ends of the branches. The stems the berries hang off of are bright red

- Bark: Bark on younger branches is grey with little dots. As the bark is older, it is sometimes grey with a reddish tint, sometimes a brownish-grey that breaks up vertically and horizontally into scales.

- Habitat: Damp areas, such as the edge of wetlands, along creeks and beside rivers, edges of woodlands, in not too shaded areas of woods. Does well in alkaline to neutral soils.

Web Resources:

- Recipe search on the web here (Google search) and here (Bing search).

- Pictures on the web here (Google images) and here (Bing images).

- Pictures of the fruit on the web here (Google images) and here (Bing images).

- Interactive USDA distribution map and plant profile here.

- The Biota of North America Program (BONAP) distribution map here. BONAP map color key here.

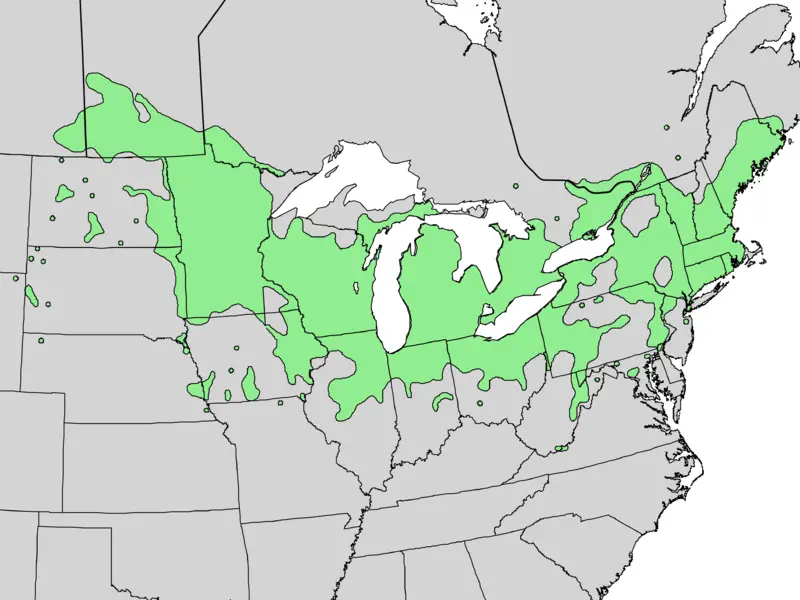

Nannyberry (Viburnum lentago) range. Distribution map courtesy of the USGS Geosciences and Environmental Change Science Center, originally from "Atlas of United States Trees" by Elbert L. Little, Jr. .

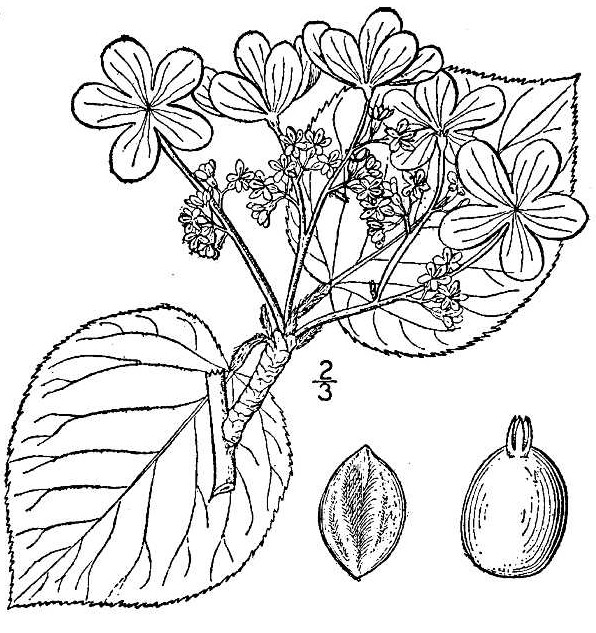

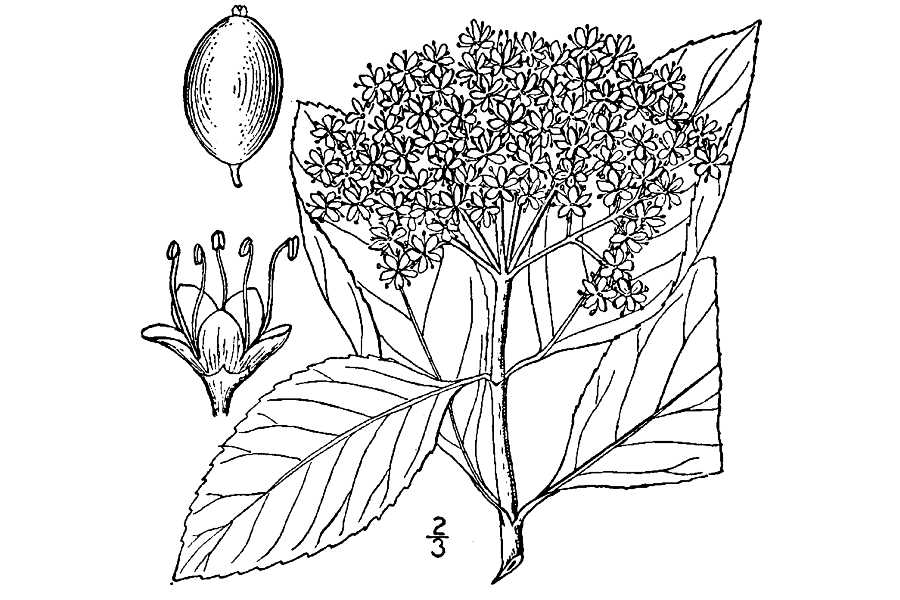

Nannyberry (Viburnum lentago) drawing. (USDA-NRCS PLANTS Database / Britton, N.L., and A. Brown. 1913. An illustrated flora of the northern United States, Canada and the British Possessions. 3 vols. Charles Scribner's Sons, New York. Vol. 3: 273.)

Nannyberry (Viburnum lentago) leaves. (USDA-NRCS PLANTS Database / Herman, D.E., et al. 1996. North Dakota tree handbook. USDA NRCS ND State Soil Conservation Committee; NDSU Extension and Western Area Power Administration, Bismarck.)

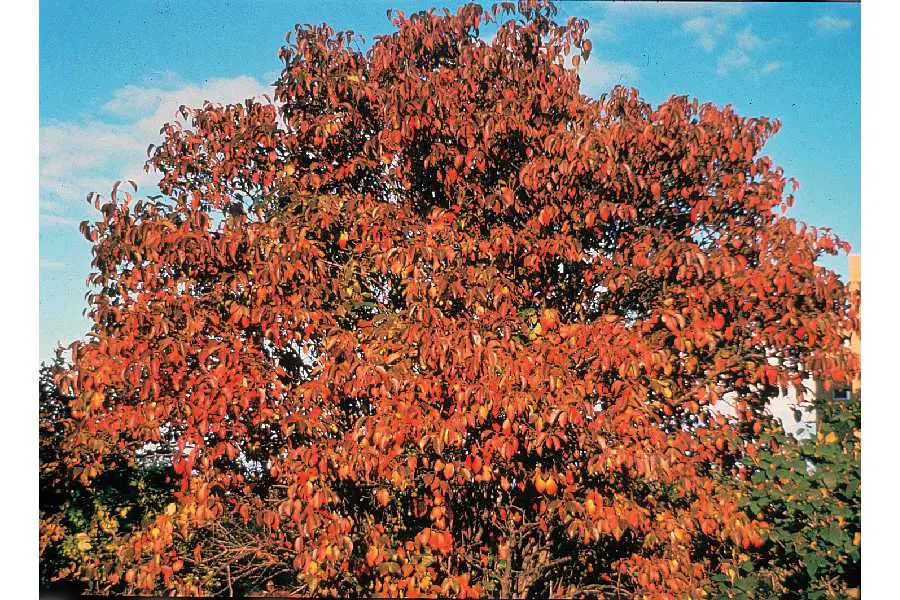

Nannyberry (Viburnum lentago) fall colors. (USDA-NRCS PLANTS Database / Herman, D.E., et al. 1996. North Dakota tree handbook. USDA NRCS ND State Soil Conservation Committee; NDSU Extension and Western Area Power Administration, Bismarck.)

Nannyberry (Viburnum lentago) in flower. (Douglas Ladd, hosted by the USDA-NRCS PLANTS Database / USDA SCS. 1989. Midwest wetland flora: Field office illustrated guide to plant species. Midwest National Technical Center, Lincoln.)

Nannyberry (Viburnum lentago) unripe fruit. (By: Vojtěch Zavadil CC BY-SA 3.0)

Nannyberry (Viburnum lentago) Trunk and bark. (By: Vojtěch Zavadil CC BY-SA 3.0)

Nannyberry (Viburnum lentago) ripe fruit and fall colors. (Herman, D.E., et al. 1996. North Dakota tree handbook. USDA NRCS ND State Soil Conservation Committee; NDSU Extension and Western Area Power Administration, Bismarck. Courtesy of ND State Soil Conservation Committee. Provided by USDA NRCS ND State Office. United States, ND

Nannyberry (Viburnum lentago) ripe fruit up close. (By: R. A. Nonenmacher Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license)

Hobblebush

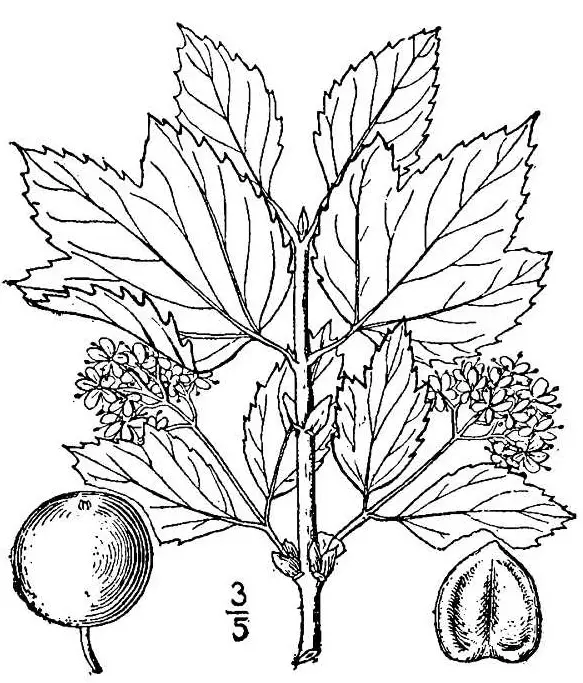

Hobblebush (Viburnum lantanoides or Viburnum alnifolium). Also known as the Alder-leaved Viburnum, Moosewood and Witch-hobble. The plant has a habit of the branches leaning over and the tips of the branches touching the ground and taking root. This makes a hoop of branch attached at both ends to the ground making it easy to trip over - hence the name Hobblebush. This bush is more common in acidic soils, so expect to find it in the same general areas as Blueberries and other acidic soil loving plants. This is a plant that can tolerate a good amount of shade. When fully ripe the fruit is blue to purple-black, but before it is fully ripe it is first green, then pink, then red. Early fall is best time to find them.

If you have a place on your property that is shaded, acidic and wet to damp, this would be a great choice. Nice looking and food producing. If you plant from seed, plant a few after the flesh has been removed and be prepared to wait two years before it sprouts - this is normal for a Viburnum. Since it takes root from the branch tips, you could find one, cut the hooped branch in the center, dig up one rooted side, take home and plant. Or, take a cutting and push it into the ground where it is damp and shaded. You could also take cuttings the other ways mentioned in the introduction to Viburnums as well.

The fruit is raisin or date like, and can be eaten raw, but there is little flesh as the seed takes up most of the space in the fruit. If you gather enough, cook them with water, strain out the seeds, and use the remaining pulp or liquid. You can make jams and jellies, but you can also use this in baked goods for a raisin/date like taste, and even drinks. The pulp/juice goes well with many foods, just use some as flavoring in stir fry's or baked dishes. Seems to work well with curried dishes. Adds a different angle to the flavor without overpowering other flavors. You can store extra by putting the pulp in baggies and freezing and use when needed.

Description:

- USDA Plant Hardiness Zone: 2-9 (More information on hardiness zones).

- Soil pH: 5.5-6.5

- Plant Size: Up to 3-4.5 meters (10-15 feet) tall, but very often found much shorter

- Duration: Perennial Shrub

- Leaf Shape: Round to Ovate to heart shaped with pointed tip

- Leaf Phyllotaxis (Arrangement) on branch: Opposite, at end of branch there are also two opposite leaves, not a single terminating leaf

- Leaf Size: 10-20 cm (4 to 8 inches) long

- Leaf Margin: finely Serrated (saw toothed edge)

- Leaf Notes: The color of the leaves is variable - sometimes light shiny green, sometimes medium green. Leaf veins are obvious, and very obvious when looking though the leaf while holding it up to light. Very often, but not always, the leaves have a very fine wrinkly quality where the wrinkle creases are perpendicular to the leaf veins. Can take a purplish-red, red, orange, yellow-green or mottled with more than one color in fall

- Flowers: Small white (sometimes light pink) flowers in clusters 15-20 cm (6 to 8 inches) diameter

- Fruit: Blue to purple-black when fully ripe, first green, then pink, then red when unripe

- Bark: Older branches can be grey and fissured finely, younger branches have a reddish hue. Nothing particularly distinguishing about the bark

- Habitat: Associated with shaded areas in woods, prefers acidic damp soils so it is often by water of any kind. Due to its habit of rooting from where the branches touch the ground, there can be areas full of it.

Web Resources:

- Recipe search on the web here (Google search) and here (Bing search).

- Pictures on the web here (Google images) and here (Bing images).

- Interactive USDA distribution map and plant profile here.

- The Biota of North America Program (BONAP) distribution map here. BONAP map color key here.

Hobblebush (Viburnum lantanoides or Viburnum alnifolium) range. Distribution map courtesy of U. S. Department of Agriculture (USDA Natural Resources Service) and used in accordance with their policies.

Hobblebush (Viburnum lantanoides or Viburnum alnifolium) drawing. (USDA-NRCS PLANTS Database / Britton, N.L., and A. Brown. 1913. An illustrated flora of the northern United States, Canada and the British Possessions. 3 vols. Charles Scribner's Sons, New York. Vol. 3: 269.)

Hobblebush (Viburnum lantanoides or Viburnum alnifolium) in woods. (By: Richtid GNU Free Documentation License, Version 1.2)

Hobblebush (Viburnum lantanoides or Viburnum alnifolium) leaf and flowers. (By: Wladyslaw GNU Free Documentation License, Version 1.2)

Squashberry

Squashberry (Viburnum edule). Also known as the Highbush Cranberry, Lowbush Cranberry, Mooseberry, Pembina, Pimbina. The Viburnum trilobum is usually the species referred to as the Highbush Cranberry, but this shows why it is a good idea to use the Latin names for double checking, even if you don't know how to pronounce them. Neither is related to the true Cranberries which are in the Vaccinium genus, not the Viburnum.

Nice choice overall if you have a place where the soil stays cool and moist with sun to part shade. Nice looking all year, and the red leaves in fall are beautiful. You can start by seed (I think some nurseries carry this one), and cuttings. If you do start by seed, remember, Viburnum seeds don't sprout until the second year planted.

This one can easily be mistaken for the Viburnum trilobum. So, how do you tell the difference? The most reliable way is by where you find it. If you are in a northern boreal forest, and find one in a damp area, it is most likely the Squashberry - the Viburnum edule. If you are where the dominant forests around are not boreal, and the soil is more likely alkaline and the ground where it is growing is not wet/damp (but could be near water), then most likely it is the Viburnum trilobum. Just don't mistake for the naturalized Viburnum opulus, which can look very similar (identical, if you ask me). See the section on the Viburnum trilobum here to how to know when you have a Viburnum opulus. As long as you don't have the Viburnum opulus, treat them the same in how you cook and eat, though this one is actually better tasting - especially fresh.

The red to orange fruit from this Viburnum is a refreshing tart/sweet. Because of a shallow dimple where the stems attach to the fruit, they look like sour Cherries to me, but with a more translucent quality. Very good for jams and jellies, and a refreshing snack while walking. Since the flat pit is large, best to scrape the flesh off the pit with your front teeth. It is the tart quality, that when cooked, makes the jams and jellies made from it, have a bright, clear taste. Very good spread on toast. Should be a commercially grown crop for jams and jellies, but as far as I know, is not. You can cook it like Cranberries and use the same way as well, and that is where the two common names with Cranberry in them come from. Don't be distressed when cooking them, there is a smell in the air that is not pleasant - this is normal, and will not be there in the finished product. It is a dirty clothes to musky smell.

Since the pit has to be removed before cooking (to prevent any bitterness), the easiest way is to freeze what you have picked, then crush and sieve, then cook. You can just squash them fresh and mix with water and sieve, and cook down the water.

Description:

- USDA Plant Hardiness Zone: 3-10 (More information on hardiness zones).

- Soil pH: no data, but most commonly found in soils of pH 6.5

- Plant Size: Up to 2-3.7 meters (6 to 12 feet) high

- Duration: Perennial

- Leaf Shape: Three lobes Maple leaf like to Ovate. Variable with the middle lobe much higher up than the side lobes, to all three lobes terminating at the same height giving a three point crown look.

- Leaf Phyllotaxis (Arrangement) on branch: Opposite, at end of branch there are also two opposite leaves, not a single terminating leaf

- Leaf Size: Up to 10 cm (4 inches) long and wide.

- Leaf Margin: Serrated (saw toothed edge) - irregular pattern

- Leaf Notes: Leaves turn a bright red in the fall. Terminal pair of leaves are sometimes not lobed, while the rest are. Undersides of leaves can be sparsely hairy.

- Flowers: Small clusters of all white five petalled flowers, buds have a dull pink-maroon tone

- Fruit: 6-12 mm long, red, cherry shaped fruit with an almost translucent quality. Clusters of fruit can be horizontal, hanging or upright. Fruit stems are a soft, light red. One flat seed in the pit. There is a shallow dimple where the fruit attaches to the fruit stem. The fruit is first green, then yellow, the yellow and red, then when ripe, bright red, often with a very slight orange quality to the red.

- Bark: Younger branches have a blotchy brown and tan coloration often with occasional lenticels (checking).

- Habitat: Sunny to part shade, moist, cool soils. Associated with boreal forests in damp areas, very often near water. Generally like neutral to slightly acidic soils.

Web Resources:

- Recipe search on the web here (Google search) and here (Bing search).

- Pictures on the web here (Google images) and here (Bing images).

- Interactive USDA distribution map and plant profile here.

- The Biota of North America Program (BONAP) distribution map here. BONAP map color key here.

Squashberry (Viburnum edule) range. Distribution map courtesy of U. S. Department of Agriculture (USDA Natural Resources Service) and used in accordance with their policies.

Squashberry (Viburnum edule) drawing. (USDA-NRCS PLANTS Database / Britton, N.L., and A. Brown. 1913. An illustrated flora of the northern United States, Canada and the British Possessions. 3 vols. Charles Scribner's Sons, New York. Vol. 3: 270.)

Squashberry (Viburnum edule) leaf and flowers. (By: Dave Powell, USDA Forest Service CC BY-SA 3.0)

Squashberry (Viburnum edule) ripe fruit and leaves. (By: Dave Powell, USDA Forest Service CC BY-SA 3.0)

Squashberry (Viburnum edule) in woods. (By: Dave Powell, USDA Forest Service CC BY-SA 3.0)

Possumhaw

Possumhaw (Viburnum nudum or Viburnum nudum var. nudum). Known also as the Naked Viburnum, Smooth Witherod, Wild Raisin. Some sources include the Viburnum cassinoides as one and the same as the Viburnum nudum. In fact, some sources say that the names Viburnum nudum and Viburnum cassinoides are synonyms. The Viburnum cassinoides is often named the Viburnum nudum var. cassinoides and both can be called the Wild Raisin (Though the Viburnum cassinoides is also called the Northern Wild Raisin). Comparing the USDA range maps, shows they have two separate ranges, and some taxonomists do say they are one and the same - but variations of the same plant displaying different characteristics in different climate zones. So, here we have two very similar species that might be variations of one, but do have some distinguishing characteristics. The description below is specific to the one you will find in the very Southeast and up along the Eastern shore of the USA - the one in the USGS map below the USDA map.

Like most Viburnums, takes well from cuttings done in spring and should start from seed without issue. Wet to well drained moist soils. Best in full sun, will handle some shade though providing fewer flowers and fruit. Does fine in acidic to neutral soils. But, considering the questions regarding taste, I recommend the Northern Wild Raisin instead.

A serious caution: This shrub has opposite, glossy, sometimes wavy edged leaves that are often Elliptic in shape. If you are not absolutely clear on the difference between compound and simple leaves, you could very easily mistake this bush for the Poison Sumac. The Poison Sumac has leaflets (NOT leaves) that are similar in size to the leaves of the Possumhaw. The Poison Sumac leaflets are opposite on the leaf, glossy, sometimes wavy edged and are often Elliptic. Look here if you are not 100% sure of the difference between simple and compound leaves. The Poison Sumac and this Viburnum can be right in the same places, and confusing them could be a very serious mistake. The leaves are alternate on the Poison Sumac, so if you are very clear on the difference, you will not mistake them.

Most people say this one tastes like raisins to a bit like prunes, but there are reports of it being bitter, or raisin like with a bitter aftertaste, to being highly acidic to the point of being barely edible, or even reports of it being sweet. I'm not sure if that is variation in the species, picking them at different stages, the climate/soil they are in or what, but I have a guess. It seems most of the reports of it being sweet and good come from Canada or the Northeastern USA, while the reports of it being either good or not good come more from the Southeastern USA. So, I think the Northern Wild Raisin (Viburnum cassinoides) is the good tasting one - which can also be found in a lot of the Southeast as well, and the Viburnum nudum is the poor tasting one. I have no way of proving this, it is just a theory on my part, however if that can be proved to be the case, it does give strength to the idea they should be regarded as two separate species. Considering all the above, I would avoid eating the fruit from this one, and stick to the Northern Wild Raisin, but if you identify it as this one, and like the taste, you will have to make your own decisions.

Description:

- USDA Plant Hardiness Zone: 5-9 (More information on hardiness zones).

- Soil pH: 5.6-6.0

- Plant Size: 3-6 meters (10 to 20 feet) tall

- Duration: Perennial Shrub to small tree

- Leaf Shape:Simple, Elliptic to sometimes Obovate

- Leaf Phyllotaxis (Arrangement) on branch: Opposite

- Leaf Size: 7.5-12.5 cm (3 to 5 inches) long

- Leaf Margin: Entire (smooth edged) and very often wavy at the edges. Sometimes there is a bumpy edge that could be thought of as shallow, irregular, rounded serrations, though technically not.

- Leaf Notes: Very glossy upper surface

- Flowers: Small creamy while flowers in flat to slightly domes clusters on long stems

- Fruit: Oval, approx. 8 mm (1/3 inch) long. First green, then pink the blue to purple-blue when ripe in large clusters. Each fruit has a single hard, round, flattened seed

- Bark: Brown-grey, smooth with raised bumps or lenticels (checking). Twigs are reddish-brown and glossy

- Habitat: Does tend to be more common in wet to mucky soils, however, can do fine in moist, well drained soils. Sun to partial shade. In the wild generally found in damp areas by marshland, streams and rivers. From acidic to neutral soils.

Web Resources:

- Recipe search on the web here (Google search) and here (Bing search).

- Pictures on the web here (Google images) and here (Bing images).

- Interactive USDA distribution map and plant profile here.

- The Biota of North America Program (BONAP) distribution map here. BONAP map color key here.

Possumhaw (Viburnum nudum) range. Distribution map courtesy of the USGS Geosciences and Environmental Change Science Center, originally from "Atlas of United States Trees" by Elbert L. Little, Jr. .

Northern Wild Raisin

Northern Wild Raisin (Viburnum cassinoides or Viburnum nudum var. cassinoides). Also known as the Swamphaw, Wild raisin, Witherod Viburnum, Withe-rod. I have a name suggestion: the Stink Tree. There are times when you walk past one of these, and there is a bad smell coming from it. If you live in the Southeast or Eastern Shore of the USA, make sure you read the entry on the Possumhaw (Viburnum nudum) as there is confusion with these two.

Nice looking shrub any time of the year - the fruit is amazing looking when unripe and bright pink, the fruit is good tasting, will grow in a wide range of soils, and will tolerate partial shade. Like most Viburnums, cuttings should take without too much trouble. Keep in mind, it does smell like dirty laundry when in flower.

A serious caution: This shrub has opposite, glossy, sometimes wavy edged leaves that are often Elliptic in shape. If you are not absolutely clear on the difference between compound and simple leaves, you could very easily mistake this bush for the Poison Sumac. The Poison Sumac has leaflets (NOT leaves) that are similar in size to the leaves of the Northern Wild Raisin. The Poison Sumac leaflets are opposite on the leaf, glossy, sometimes wavy edged and are often Elliptic. Also the Northern Wild Raisin has a pair of leaves at the end of each twig, while the Poison Sumac has a single leaflet at the end of each leaf. Read here if you are not 100% sure of the difference between simple and compound leaves. The Poison Sumac and this Viburnum can be right in the same places, and confusing them could be a very serious mistake. The leaves are alternate on the Poison Sumac, so if you are very clear on the difference, you will not mistake them. Go to the Poison Sumac section, and get to know it very well.

Despite the smell of the tree and flowers, the fruit is very good - sweet and raisin to prune like - it's a shame there is so little flesh on each one, but it does have quality if not quantity. This one is very similar to the Nannyberry (Viburnum lentago), and you can refer to that entry here for instructions on how to use the fruit.

Description:

- USDA Plant Hardiness Zone: 3-8 (More information on hardiness zones).

- Soil pH: 5.6-6.0

- Plant Size: Up to 4 meters (13 feet) tall

- Duration: Perennial Shrub

- Leaf Shape: Quite variable, from Lanceolate to Elliptical to Obovate

- Leaf Phyllotaxis (Arrangement) on branch: Opposite

- Leaf Size: 2.5–15 cm (1 to 6 inches) long, 1.5–6 cm (2/3 to 2 1/3 inches) wide

- Leaf Margin: Quite variable, Entire (smooth edged) to Serrated (saw toothed edge) to wavy

- Leaf Notes: Glossy on the upper side, though sometimes with a dull waxy bloom that will rub off.

- Flowers: 3-10 cm ( to inches) diameter clusters of flat topped to slightly domes white flower with an unpleasant scent. The very similar Nannyberry (Viburnum lentago) has sweet smelling flowers.

- Fruit: Sweet, tasty, oval shaped berry (drupe technically) that is about 6-9 mm (1/4 to 1/3 inch) long with a 1 seeded pit. First white, then bright pink, then blueish-black with bloom. Starts to turn wrinkly when ripe in the middle to late summer. The stems that hold the fruit are a pink-red

- Bark: Brown-grey, smooth with raised bumps or lenticels (checking). Twigs are reddish-brown and glossy

- Habitat: Seems to have a very broad range of habitats from wet to moist land in open woods, swampy area, along shores of rivers and streams in boreal to mixed forest regions. Acidic to neutral soils, sun to part shade.

Web Resources:

- Recipe search on the web here (Google search) and here (Bing search).

- Pictures on the web here (Google images) and here (Bing images).

- Interactive USDA distribution map and plant profile here.

Wild Raisin (Viburnum cassinoides or Viburnum nudum var. cassinoides) range. Distribution map courtesy of U. S. Department of Agriculture (USDA Natural Resources Service) and used in accordance with their policies.

Wild Raisin (Viburnum cassinoides or Viburnum nudum var. cassinoides) drawing. (USDA-NRCS PLANTS Database / Britton, N.L., and A. Brown. 1913. An illustrated flora of the northern United States, Canada and the British Possessions. 3 vols. Charles Scribner's Sons, New York. Vol. 3: 272.)

Wild Raisin (Viburnum cassinoides or Viburnum nudum var. cassinoides) seeds. (Carole Ritchie, hosted by the USDA-NRCS PLANTS Database)

Wild Raisin (Viburnum cassinoides or Viburnum nudum var. cassinoides) leaves and flower buds. Please note how similar these leaves look compared to Poison Sumac leaflets. Also be aware the margins of the leaves can be smooth (entire) to sawtooth to wavy. (By: Brett Marshall CC BY-SA 3.0)

Wild Raisin (Viburnum cassinoides or Viburnum nudum var. cassinoides) flowers. (By: Dcrjsr )

Wild Raisin (Viburnum cassinoides or Viburnum nudum var. cassinoides) twig end. Note how there is a pair of opposite leaves at the end - not a single leaf like the Poison Sumac. (By: Rob Routledge CC BY-SA 3.0)

Wild Raisin (Viburnum cassinoides or Viburnum nudum var. cassinoides) not quite mature (white/pink) and mature (blue) fruit. Again, be careful - the Poison Sumac can have whitish/green fruit clusters. (By: Rob Routledge CC BY-SA 3.0)

Blackhaw

Blackhaw (Viburnum prunifolium). Also called the Black Haw, Blackhaw Viburnum, Sweet Haw, and Stag Bush. I don't have these where I live, but have included a description of them for those that live where they grow.

Nice looking, slow growing, takes well from cuttings, transplanting of root suckers and from seed.

A serious caution: This shrub has opposite, glossy, leaves that are similar in shape to Poison Sumac leaflets. If you are not absolutely clear on the difference between compound and simple leaves, you could very easily mistake this bush for the Poison Sumac. Read here if you are not 100% sure of the difference between simple and compound leaves. The Poison Sumac and this Viburnum can occur in the same places, and confusing them could be a very serious mistake. The leaves are alternate on the Poison Sumac, and do not have serrations on the leaflet edges like the Blackhaw leaves do, so if you are very clear on the difference, you will not mistake them.

Second Caution: The fruit contains Salicin, which is a natural form of Aspirin, so if you are allergic to Aspirin (ASA), don't eat these. Because of this, this plant more of a medicinal than food, and recommend you only eat small amounts. Also, if you take Aspirin each day in specific amounts by recommendation of a doctor, I would not eat these. Also, because of Reye's syndrome, children under 12 and teenagers should probably not eat these.

Description:

- USDA Plant Hardiness Zone: 3-9 (More information on hardiness zones).

- Soil pH: 6.0-6.5

- Plant Size: Up to about 6 meters (20 feet) tall

- Duration: Perennial Shrub to small tree

- Leaf Shape: Ovate

- Leaf Phyllotaxis (Arrangement) on branch: Opposite

- Leaf Size: Up to 7.5 cm (3 inches) long

- Leaf Margin: Serrated (saw toothed edge)

- Leaf Notes: Very glossy upper surface

- Flowers: Up to 10 cm (4 inches) wide clusters of white petalled flowers

- Fruit: Immature fruit can be green, yellow or pinkish-red turning to a pink-blue to black-blue when mature, often with a bloom on fruit surface

- Bark: Dense branching, twigs are grey and smooth, younger trunks are a brown-grey and smooth, while older trunks bark breaks into plates and is grey-black.

- Habitat: Sun to shade. Can grow in wide variety of soils, moisture conditions and acidity.

Web Resources:

- Recipe search on the web here (Google search) and here (Bing search).

- Pictures on the web here (Google images) and here (Bing images).

- Interactive USDA distribution map and plant profile here.

- The Biota of North America Program (BONAP) distribution map here. BONAP map color key here.

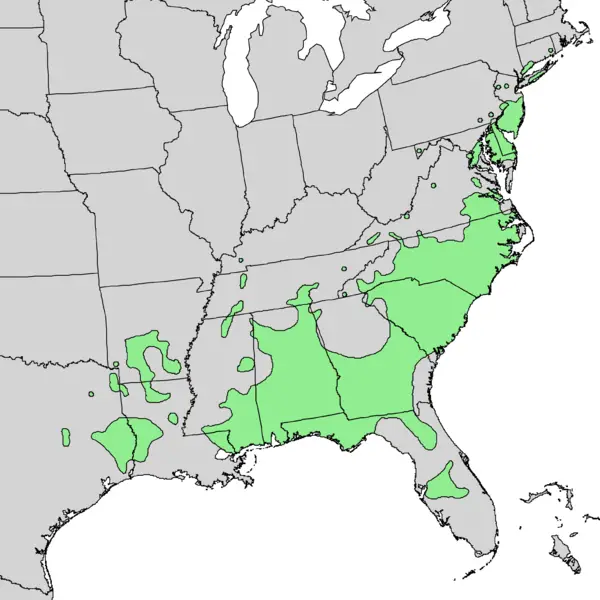

Blackhaw (Viburnum prunifolium) range. Distribution map courtesy of the USGS Geosciences and Environmental Change Science Center, originally from "Atlas of United States Trees" by Elbert L. Little, Jr. .

Rusty Blackhaw

Rusty Blackhaw (Viburnum rufidulum). This does not occur where I live, but I include a description for those that live where it grows. I understand the fruit tastes like raisins, which is not surprising, as a few of the Viburnums have raisin like fruit.

Nice looking tree/shrub, but will spread aggressively by the roots.

Description:

- USDA Plant Hardiness Zone: 4-8 (More information on hardiness zones).

- Soil pH: 5.6-6.0

- Plant Size: Up to 6 meters (20 feet) tall

- Duration: Perennial Shrub to small tree that forms clonal colonies

- Leaf Shape: Ovate to Obovate

- Leaf Phyllotaxis (Arrangement) on branch: Opposite

- Leaf Size: Up to 7.5 cm (3 inches) long and 3.75 cm(1.5 inches) wide

- Leaf Margin: Serrated (saw toothed edge)

- Leaf Notes: Glossy upper surface. With rust colored hairs on the leaf stem, leaf underside

- Flowers: Up to 12.5 cm (5 inches) diameter clusters of small white flowers

- Fruit: Purple to dark blue when ripe

- Bark: Young twigs have the rust colored hairs. Mature trunks bark is broken into deep plates that can be grey to charcoal grey.

- Habitat: Likes well drained soils, and tends to be found in dryer locations in full sun to part shade

Web Resources:

- Recipe search on the web here (Google search) and here (Bing search).

- Pictures on the web here (Google images) and here (Bing images).

- Interactive USDA distribution map and plant profile here.

- The Biota of North America Program (BONAP) distribution map here. BONAP map color key here.

Rusty Blackhaw (Viburnum rufidulum) range. Distribution map courtesy of the USGS Geosciences and Environmental Change Science Center, originally from "Atlas of United States Trees" by Elbert L. Little, Jr. .

Search Wild Foods Home Garden & Nature's Restaurant Websites:

Share:

Why does this site have ads?

Originally the content in this site was a book that was sold through Amazon worldwide. However, I wanted the information to available to everyone free of charge, so I made this website. The ads on the site help cover the cost of maintaining the site and keeping it available.

Google + profile