Search Wild Foods Home Garden & Nature's Restaurant Websites:

Oak Trees

(NOTE: If you are not interested in growing Oak Trees, but just finding the acorns and using them, try going to the Nature's Restaurant Online site Acorns page.)

With Oaks, there are three basic groups: The White Oaks, The Chestnut Oaks and the Red or Black Oaks. Some sources say there are only two groups, and the Chestnut Oak group is considered part of the White Oak group.

In the east, there are two "White Oaks" with one season acorns and irregular, deep, rounded lobe leaves:

- The White Oak (Quercus alba)

- The Bur Oak (Quercus macrocarpa)

There are three "Chestnut Oaks" also with one season acorns:

- The Swamp White Oak (Quercus bicolor)

- The Chinquapin or Chinkapin Oak (Quercus muehlenbergii)

- The Chestnut Oak (Quercus prinus or Quercus montana)

The third group is the "Red or Black Oaks" with two season acorns and sharply pointed leaves:

- The Red Oak (Quercus rubra)

- The Black Oak (Quercus velutina)

- The Pin Oak or Swamp Spanish Oak (Quercus palustris)

There are many other smaller oaks in Eastern North America, and there are at least two more that are large tree size and planted that are not native to North America. They are the English Oak (Quercus robur) and Durmast Oak (Quercus petraea or Quercus sessiliflora). I cannot speak for the Durmast Oak, but I would not eat the English Oak acorns again - too bitter, and why bother when there are better ones around is my reasoning.

Only use acorns from either the White Oak group or the Chestnut Oak group. NEVER use the Acorns from the Red, Black or Pin Oak. The acorns from the Black Oak contain phenolics - a poison. It is hard for the beginner to tell the Red from Black Oak. Also, Red Oaks and Black Oaks can interbreed, giving a tree that looks like a Red Oak that makes acorns with the Black Oak toxin. Also, the Red and Pin Oak acorns require much more processing to make them edible than either the Bur or White Oaks due to very high tannin levels in them. Make sure before you gather any White or Chestnut Oak acorns, that there are not Red, Black or Pin Oak trees very close, as the acorns on the ground could be a mix of the two. If not absolutely sure, don't bother gathering at that spot. The "bad" three - Red, Black and Pin Oak are easy to spot, they all have leaves with sharply pointed lobes - see included pictures at the end of this acorn section.

The advantages of the Bur Oak are: 1 - the acorn is a bit larger than the others, therefore you get more for the effort. 2 - it is outright the best tasting. 3 - requires the least processing. Chinkapin Oaks have very good acorns, and they do grow faster and produce sooner than the Bur or White Oak.

Planting: So, if you decide to grow an Oak tree, and want one that will bear edible Acorns, and have chosen which one, the task is easy. Plant an acorn in the fall where you want it about 5 cm (2 inches) deep. See the section on Black Walnuts for ideas on how to prevent squirrels for digging them back up.

Transplanting: The Bur Oak can be transplanted, and I've done many myself. Do it in the late fall or early spring and get as much of the roots as you can. Take your time and get a good sized root ball. I've never tried to transplant any of the Chinkapin Oaks or the White Oak, but the general advice is always the same: in the late fall or early spring, the smaller the tree the better, get as much of the root system as possible, put in similar conditions it came from, mulch around it, and don't let the soil dry out in the first season.

Soil & Site: See the descriptions for each one to determine the soil pH, soil types and sites. All like full sun.

Maintenance: There is nothing to do with any of these, except for keeping the ground moist in the first season if yours is a transplanted tree.

Harvesting: They are ready to harvest as soon as they hit the ground, don't bother trying to pick from a tree. First, you have to remove the outer husk (the cap or cup that holds the acorn). The acorn is generally loose fitting in the husk when ripe. If it is tight, I find it to be a sign that there is a worm in the acorn – just the same as with a Hickory nut. Whatever works best for you to remove the husk. For me, a dull paring knife is good for the Bur Oak. With the White Oak, it usually just falls off. You can then separate the good from bad by putting them in water. If they float, toss them, only ones that sink are saved for the next steps.

Using: Before using, you have to remove the leathery shell. Some people first put them in an oven at a very low temp 150-175 F. for 15-20 minutes at this point, I don't. Again, experiment and find what work best. Here is what I like to do: with a few at a time on a cutting board with a cloth on it (old, clean washcloth is good) so they don't roll around, use a larger, sharp kitchen knife (and NOT holding the acorn with your fingers), roll the knife from the blade tip to handle in a single quick roll, cutting the acorn in half shell and all. After you have done a bunch this way, remove the nut half from the shell. When done this way, there is no doubt whether it is worm free or not. Some use a nutcracker, but if you do you might want to do the 15-20 minutes in the oven first.

Now, the next step - the leaching out of the bitter tannins - has a lot of variations. Because I use Bur Oak acorns, I skip this step completely. You can soak the nut meat in room temperature water, changed at least once per day for one, two or more times. When I did this, I put a little salt in the water, but I've never heard of anyone else doing that. Not sure how I started doing that. Another way is to put the acorn meat in water that is already boiling (don't put in cold water and heat up), simmer for 15-20 minutes. Depending on the type of acorn, you may need to do this more than once.

At this point, you can use them. Grind them up in a blender and add to baked goods or other meals. I more often than not like to roast them before using.

To roast, put on cookie sheets in oven at about 300-350 F in an oven and roast until dry and just starting to turn golden. Take out and cool down when done.

You can grind them into flour in a grain mill or coffee grinder. I find the grain mill bogs down with acorns, so I suggest a few at a time in a coffee grinder. 10 - 20% acorn flour when making bread works fine, and gives a nutty tasting bread.

If you don't want them made into flour, you can put the roasted halves between two clean, old dishcloths, and hammer them gently with a wooden or hard rubber mallet and use the small bits in baked goods. Added to bread dough this way makes a nutty textured bread. You can also use the bits to add to stir-fry meals to add a bit of crunch without adding a strong flavor. The roasted halves or flour keep well frozen in baggies to use throughout the year.

If, you want to use them right away after harvest for making into pan bread (pancakes?), there is a way. After floating and shelling them, put in a blender with lots of water to the acorns, blend fine and strain through a clean cloth and use. Twist the cloth tight around each batch to squeeze out the water. If you do this, my suggestion is to use no more than 25% acorn mash to 75% buckwheat flour.

Web Resources:

Recipe search on the web here (Google search) and here (Bing search).

White Oak

White Oak (Quercus alba):Beautiful tree. Slow growing, so don't expect any acorns for at least 20 years - more likely 40-50, but you are doing a great favor to future generations by planting this tree. Beautiful red and yellow fall leaf color.

- USDA Plant Hardiness Zone: 3-8 (More information on hardiness zones).

- Soil pH: 4.8-8.0

- Plant Size: In woods can be a very tall tree - 30 meters (100 feet), in the open, spreads very wide.

- Duration: Lives hundreds of years.

- Leaf Shape: Simple, highly variable with 7-9 deep, narrow, irregular rounded lobes

- Leaf Phyllotaxis (Arrangement) on branch: Alternate

- Leaf Size: Generally about (6 inches) long by (3 inches) wide

- Leaf Margin: Mostly Entire (smooth edged), but wider lobes have large rounded teeth

- Leaf Notes: Pinkish and downy when unfolding in spring, hairless when leaf is mature

- Flowers: Male flowers in long, thin clusters, female flowers single or very small groups, short

- Fruit: (1/2 to 3/4 inch) long, about 1/4 of acorn is covered by the cup or cap. The cap has no fringe (edge of cap is smooth with no fuzzy growth)

- Bark: Light grey, scaly, twigs grey-brown

- Habitat: In its range, can grow in a wide variety of soils. Often planted as an ornamental, or in deciduous forests.

Web Resources:

- Pictures on the web here (Google images) and here (Bing images).

- Interactive USDA distribution map and plant profile here.

- The Biota of North America Program (BONAP) distribution map here. BONAP map color key here.

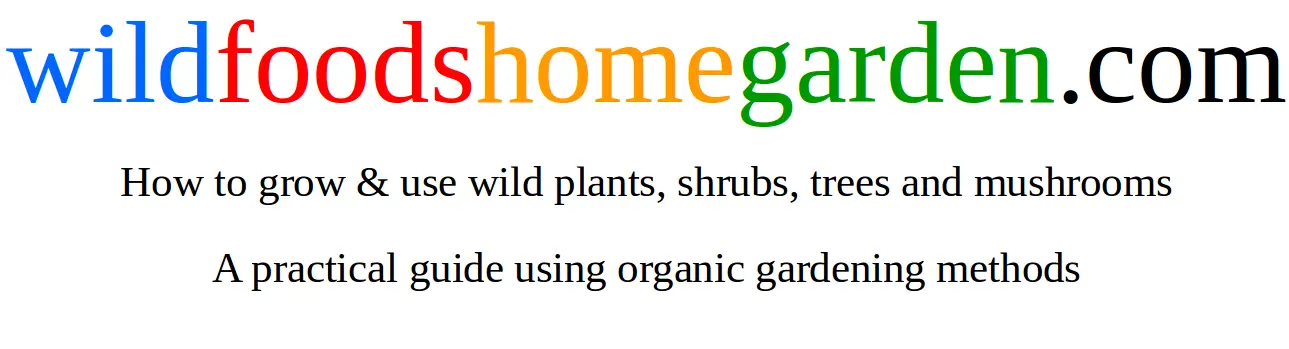

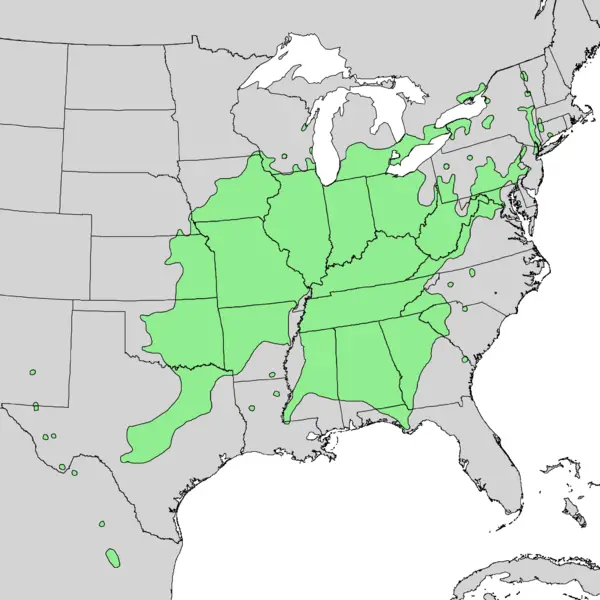

White Oak (Quercus alba) range. Distribution map courtesy of the USGS Geosciences and Environmental Change Science Center, originally from "Atlas of United States Trees" by Elbert L. Little, Jr. .

White Oak (Quercus alba) with Acorns. Notice the rounded lobes of the leaves.

White Oak (Quercus alba) illustration. (By: François André Michaux (book author), Augustus Lucas Hillhouse (translator), Pierre Joseph Redouté (illustrator), Bessin (engraver), Nonenmac (eraser))

White Oak (Quercus alba) bark. (By: Dcrjsr CC BY-SA 3.0)

White Oak (Quercus alba) fall foliage. (By: Famartin Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license)

White Oak (Quercus alba) new foliage growth in spring. (By: Famartin CC BY-SA 3.0)

White Oak (Quercus alba). Good harvest of acorns. (By: Dcrjsr CC BY-SA 3.0)

Bur Oak

Bur Oak (Quercus macrocarpa):The best one to plant for food, but it is very slow growing, and will be decades before it fruits acorns. Again, like the White Oak, you are doing future generations a favor by planting this one. Can withstand land that floods in spring then dries out. Small Bur Oaks transplant very well if you do it when the tree is dormant in early spring or late fall, and water until established. I've transplanted numerous Bur Oaks, and very few die if done carefully. In the spring of 1969 a neighbour transplanted a 3 meter (10 feet) tall one that is still alive to this day - and large now, but I would not recommend one this large normally. This tree is a great choice if you have heavy clay soils. One disadvantage with this Oak is the disappointing brown to yellow-brown fall leaf color.

- USDA Plant Hardiness Zone: 3-8 (More information on hardiness zones).

- Soil pH: 5.5-8.0

- Plant Size: Generally up to 30 meters (100 feet) tall, but can grow taller

- Duration: Slow growing tree that can live hundreds of years

- Leaf Shape: Simple leaf. Extremely variable, but with rounded lobes of varying width. A common leaf shape is lobed near base of leaf with upper section with shallow lobes or large rounded teeth. Leaf is widest nearer tip than center.

- Leaf Phyllotaxis (Arrangement) on branch: Alternate

- Leaf Size: 7–15 cm (3 to 6 inches) long and 5–13 cm (2 to 5 inches) wide

- Leaf Margin: Mostly Entire (smooth edged), but wider lobes have large rounded teeth (or very shallow lobes)

- Leaf Notes: Very fine hairs on leaf underside giving a whitish hue.

- Flowers: Female flowers small are barely noticeable in ones or small groups. Green to green-yellow male flowers in long thin clusters (catkins) in large groups.

- Fruit: Generally acorn is about (3/4 to 1 1/4 inches) long. Cap or cup (husk) covers about 1/2 to 3/4 of acorn - more than most other species, and has distinctive fuzzy fringe around it.

- Bark: Rough with deep scaly ridges or furrowed. Medium to dark grey mature bark. Small branches usually have a corky thick bark on them.

- Habitat: Found in a huge range of habitats in Eastern North America. Most common oak. Does very well in deep clay soils .

Web Resources:

- Pictures on the web here (Google images) and here (Bing images).

- Interactive USDA distribution map and plant profile here.

- The Biota of North America Program (BONAP) distribution map here. BONAP map color key here.

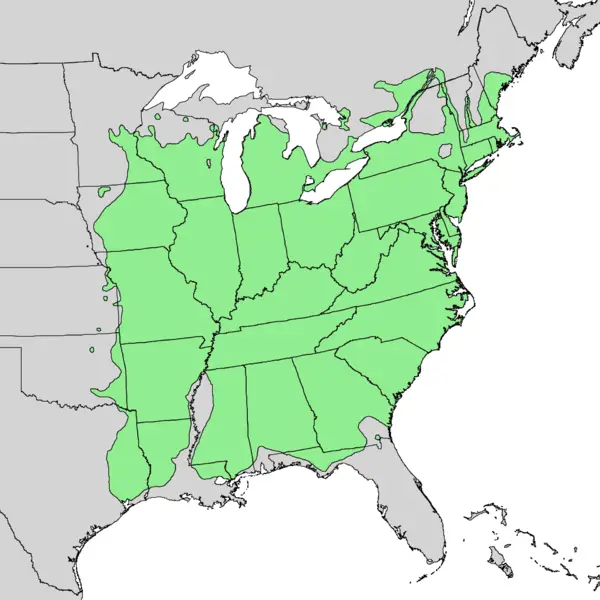

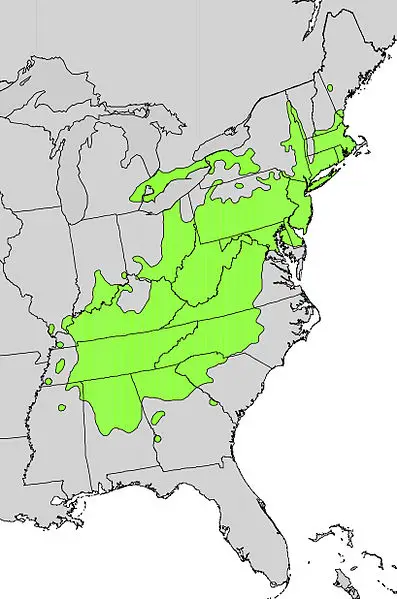

Bur Oak (Quercus macrocarpa) range. Distribution map courtesy of the USGS Geosciences and Environmental Change Science Center, originally from "Atlas of United States Trees" by Elbert L. Little, Jr. .

Bur Oak (Quercus macrocarpa) leaves with immature Acorns.

Bur Oak (Quercus macrocarpa) acorns that are ripe and will fall soon. (By: US NRCS)

Bur Oak (Quercus macrocarpa) bark. (By: Chhe)

Bur Oak (Quercus macrocarpa) illustration. (By: François André Michaux (book author), Pierre-Joseph Redouté (illustrator), Renard (engraver))

Swamp White Oak

The Swamp White Oak (Quercus bicolor):

This is a very nice tree, with pretty good acorns, and it grows faster than the other White Oaks or Chestnut Oaks (despite its name, it is a type of Chestnut Oak). A common choice for landscape use due to the speed it grows, the long time it lives, and how it doesn't grow too tall - generally not too much more than 25 meters (80 feet) tall. Good choice where there is prolonged spring flooding, but then dries out after. Fall colors can be nice, but not as nice as the White Oak.

- USDA Plant Hardiness Zone: 4-8 (More information on hardiness zones).

- Soil pH: 4.3-6.5 (ideal is 6.0)

- Plant Size: Normally up to 25 meters (80 feet) tall

- Duration: Can live hundreds of years

- Leaf Shape: Simple. Overall Ovate to Obovate with 5-7 rounded lobes on each side

- Leaf Phyllotaxis (Arrangement) on branch: Alternate

- Leaf Size: 12–18 cm (4 to 7 inches) long and 7-11 cm (3 to 4 inches) wide.

- Leaf Margin: Entire (smooth edged), though some of the smaller lobes could be described as large, rounded teeth

- Leaf Notes: Upper leaf side is shiny and medium to dark green. Underside is velvety, and a blueish-grey-green.

- Flowers: Female flowers small are barely noticeable in ones or small groups. Green to green-yellow male flowers in long thin clusters (catkins) in large groups.

- Fruit: Up to 2.5 cm (1 inch) long acorn with a cap or cup that covers about 1/3 of the acorn with a slight fringe on the edge of the cup. The distinguishing feature of this Oak is the very long stem for the acorn cup. It is between 2.5-7.5 cm (1 to 3 inches) long - very much longer than any other Eastern North American Oak.

- Bark: Scaly grey -brown

- Habitat: Generally found in moist soils near water in bottomlands. Often found where the land floods in the spring.

Web Resources:

- Pictures on the web here (Google images) and here (Bing images).

- Interactive USDA distribution map and plant profile here.

- The Biota of North America Program (BONAP) distribution map here. BONAP map color key here.

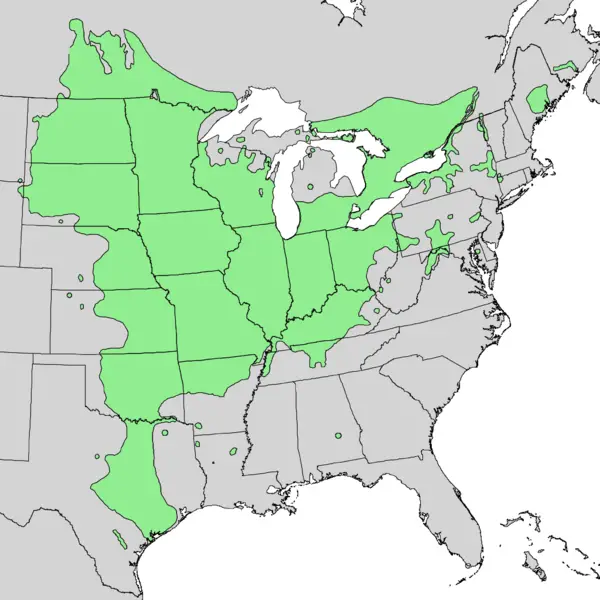

Swamp White Oak (Quercus bicolor) range. Distribution map courtesy of the USGS Geosciences and Environmental Change Science Center, originally from "Atlas of United States Trees" by Elbert L. Little, Jr. .

Swamp White Oak (Quercus bicolor) illustration. (By: François André Michaux (book author), Pancrace Bessa (illustrator), Gabriel (engraver))

Swamp White Oak (Quercus bicolor) leaves. (By: Jean-Pol GRANDMONT CC BY-SA 3.0)

Swamp White Oak (Quercus bicolor) leaves. These seem to be very different in color compared to the leaves above, but as you can see the general shape is the same. (By: Liné1 GNU Free Documentation License, Version 1.2)

Swamp White Oak (Quercus bicolor) trunk and bark on fairly young tree. (By: Liné1 GNU Free Documentation License, Version 1.2)

Swamp White Oak (Quercus bicolor) bark on a more mature tree. (By: Chhe)

Swamp White Oak (Quercus bicolor) acorns. (Steve Hurst, hosted by the USDA-NRCS PLANTS Database)

Chinquapin or Chinkapin Oak

The Chinquapin or Chinkapin Oak (Quercus muehlenbergii).

Faster growing than the Bur Oak, with acorns that are almost as good. Tree makes a nice landscaping tree that requires virtually no maintenance (true of most oaks).

- USDA Plant Hardiness Zone: 4-7 (More information on hardiness zones).

- Soil pH: 6.5-7.5

- Plant Size: In the open: up to (40 feet) tall. In woods: up to (90 feet) tall

- Duration: Over 100 years

- Leaf Shape: Elliptic to Ovate with a pointed tip

- Leaf Phyllotaxis (Arrangement) on branch: Alternate

- Leaf Size: about 12.5 cm (5 inches) long by 6.25 cm (2 1/2 inches) wide

- Leaf Margin: Large, regular, pointed triangular Serrated (saw toothed edge)

- Leaf Notes: Yellow-green and shiny on leaf upper surface. Grey-green and finely downy on the underside

- Flowers: Male: Yellow-green long, thin clusters (catkins) that droop in groups. Female: Reddish green, short, in leaf axils

- Fruit: (1/2 to 3/4 inch) long acorn with cap/cup that covers about 1/3 to 1/2 of the acorn. Cap/cup margin has no fringe

- Bark: Grey scaly bark with a slight yellowish hue to the grey.

- Habitat: Likes well drained soils with full sun and limestone based soils - often seen in stony, rocky limestone bedrock areas where the soil gets dry.

Web Resources:

- Pictures on the web for the Chinquapin or Chinkapin Oak (Quercus muehlenbergii) here (Google images) and here (Bing images).

- USDA distribution map and plant profile for the Chinquapin or Chinkapin Oak (Quercus muehlenbergii) here.

- The Biota of North America Program (BONAP) distribution map for the Chinquapin or Chinkapin Oak (Quercus muehlenbergii) here. BONAP map color key here.

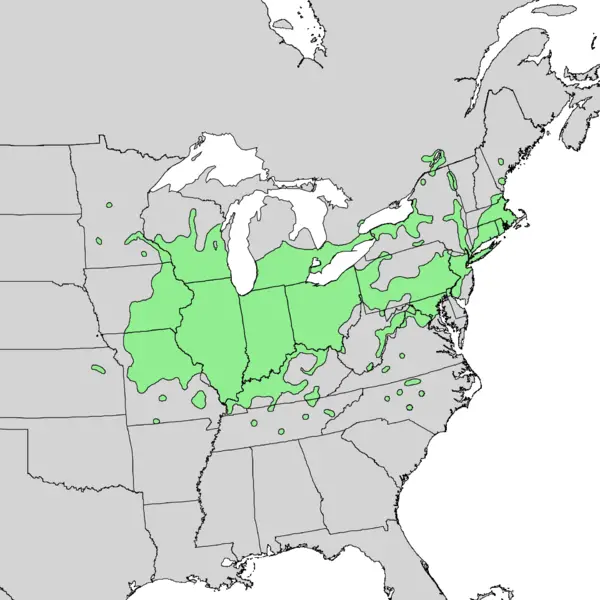

Chinquapin or Chinkapin Oak (Quercus muehlenbergii) range. Distribution map courtesy of the USGS Geosciences and Environmental Change Science Center, originally from "Atlas of United States Trees" by Elbert L. Little, Jr. .

Chinquapin or Chinkapin Oak (Quercus muehlenbergii). (By: Kim Scarborough Attribution-Share Alike 2.5 Generic)

Chinquapin or Chinkapin Oak (Quercus muehlenbergii) illustration. The name Yellow Oak and the Latin name Quercus acuminata on the bottom of the illustration are synonyms for the name of this tree. (By: François André Michaux (book author), Pierre-Joseph Redouté (illustrator), Gabriel (engraver))

Chinquapin or Chinkapin Oak (Quercus muehlenbergii) leaves and immature acorns. (By: Vojtěch Zavadil CC BY-SA 3.0)

Chinquapin or Chinkapin Oak (Quercus muehlenbergii) immature acorns up close. (By: Vojtěch Zavadil CC BY-SA 3.0)

Chestnut Oak

Chestnut Oak (Quercus montana or in the past Quercus prinus). There is confusion about this tree and its names. I'm going to quote direcetly from Wikipedia on this, "Extensive confusion between the chestnut oak (Quercus montana) and the swamp chestnut oak (Quercus michauxii) has occurred, and some botanists have considered them to be the same species in the past. The name Quercus prinus was long used by many botanists and foresters for either the chestnut oak or the swamp chestnut oak, with the former otherwise called Q. montana or the latter otherwise called Q. michauxii. The application of the name Q. montana to the chestnut oak is now accepted, since Q. prinus is of uncertain position, unassignable to either species."

Beautiful tree that should start producing acorns around the age of 20.

- USDA Plant Hardiness Zone: 5-9 (More information on hardiness zones).

- Soil pH: 4.5-7.0

- Plant Size: In the open: up to (40 feet) tall. In woods: up to (90 feet) tall. Often multiple trunks from near base of tree.

- Duration: Can live well over 100 years, reports of some living hundreds of years.

- Leaf Shape: Elliptic to Ovate

- Leaf Phyllotaxis (Arrangement) on branch: Alternate

- Leaf Size: Generally 10-15 cm (4 to 6 inches) long, though can be longer

- Leaf Margin: Very large, course, rounded Serrated (saw toothed edge)

- Leaf Notes: Shiny, dark, yellow-green above, pale green and fuzzy on the underside

- Flowers: Male: Yellow-green long, thin clusters (catkins) that droop in groups. Female: Reddish green, short, in leaf axils

- Fruit: Long - 2.5-3.75 cm (1 to 1 1/2 inches) long chestnut brown acorns. Cap/cup does not stay with acorn when fruit is mature. Cap/cup covers about 1/3 of acorn and looks like a miniature tea cup when separated from acorn. Acorn has shiny surface.

- Bark: Grey-brown. Large, distinct, deep long ridges that look like mountain ranges from above.

- Habitat: Likes well drained soils with full sun and limestone based soils - often seen in stony, rocky limestone bedrock areas where the soil gets dry.

Web Resources:

- Pictures on the web for the Chestnut Oak (Quercus montana) here (Google images) and here (Bing images).

- USDA distribution map and plant profile for the Chestnut Oak (Quercus prinus or Quercus montana) here.

- The Biota of North America Program (BONAP) distribution map for the Chestnut Oak (Quercus prinus or Quercus montana) here. BONAP map color key here.

Chestnut Oak (Quercus montana) range. Distribution map courtesy of the USGS Geosciences and Environmental Change Science Center, originally from "Atlas of United States Trees" by Elbert L. Little, Jr. .

Chestnut Oak (Quercus montana). (By: Jakec Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license)

Chestnut Oak (Quercus montana) leaves and immature acorn. (By: Mwanner GNU Free Documentation License, Version 1.2)

Chestnut Oak (Quercus montana) bark. (By: Mwanner GNU Free Documentation License, Version 1.2)

Chestnut Oak (Quercus montana) illustration. (By: François André Michaux, Augustus Lucas Hillhouse (translator), Pancrace Bessa (illustrator), Fe. Boquet (engraver))

Oaks That Have Acorns NOT For Food:

Though the Red and Black Oak are beautiful trees in their own right, they are not to be used for food purposes. Though some claim the Red Oak's acorns can be used for food if processed correctly - and they are technically correct - the problem is the Red Oak can hybridize with the poisonous Black Oak making proper identification difficult.

Leaves on a Red Oak (Quercus rubra) – notice the sharply pointed lobes of the leaves. These are what you don't want when collecting acorns to plant or eat.

Black Oak (Quercus velutina) leaves are pointed too but have a yellow hue to them. THE ACORNS FROM THIS TREE ARE POISONOUS. If the leaves have sharply pointed lobes, don't use.

Search Wild Foods Home Garden & Nature's Restaurant Websites:

Share:

Why does this site have ads?

Originally the content in this site was a book that was sold through Amazon worldwide. However, I wanted the information to available to everyone free of charge, so I made this website. The ads on the site help cover the cost of maintaining the site and keeping it available.

Google + profile