Search Wild Foods Home Garden & Nature's Restaurant Websites:

Ribes Genus: Currants & Gooseberries

Contents Of This Page:

- Wild Black Currant

- European Blackcurrant

- Northern Black Currant

- Red Currant

- Swamp Black Currant

- Skunk Currant

- Canadian Gooseberry

- American Gooseberry

- Eastern Prickly Gooseberry

- Missouri Gooseberry or Missouri Currant

- Appalachian Gooseberry

(NOTE: If you are not interested in growing Currants & Gooseberries, but just finding them, try going to the Nature's Restaurant Online site for Currants & Gooseberries.)

Gooseberries are in the same Genus as the Currants - the Ribes Genus. Some taxonomists put Gooseberry shrubs in a separate Genus from the Currants - the Grossularia. Most taxonomists however still regard Grossularia as a subgenus of Ribes, which, although does still acknowledge there are differences, says they are very similar in most ways.

So what is the main difference between Gooseberries and Currants? There are basically three. First, the stems of the Gooseberry plants have spines (prickles) on them (well, most of them), while the Currants don't. Second, the Gooseberries have flowers that are in ones to three's from short stems that come from the leaf axils (where the leaf stem meets the branch), while the Currants have racemes (clusters) of many flowers that are usually near the end of the branch. It follows then, that the fruit on the Currants comes in clusters, while with the Gooseberries the fruit comes in ones to groups of three along the branch. The third difference is in the general size of the fruit. Currants are smaller than Gooseberries. Both are at their best cooked, but some of the Gooseberries are very nice and tart fresh. By the way, some don't conform to the differences. For instance, the Swamp Black Currant (Ribes lacustre) has the prickly branches of a Gooseberry, and the multi-flowered clusters of the Currants.

All native Eastern North American Currants and Gooseberries are shrubs that are usually up to five feet (1.5 meters) tall or just slightly more. They can be found growing in a wide variety of places. By water, in woods, in fields and conifer forests. There are many ascending, leaning branches coming from the same general spot in the ground - It does not form a single trunk that branches out above the ground.

The Biota of North America Program (BONAP) distribution map for all the Ribes Genus in North America here. BONAP map color key here

Recipe search for Currants or Gooseberries on the web here (Google search).

Growing any of these should be possible. In general, the Ribes genus plants are easy to grow, and you will get a harvest quickly. The Blackcurrant (Ribes nigrum) is the most susceptible to the White Pine Blister Rust (Cronartium ribicola) as an alternate host, and is still banned from planting in many places. There are hybrids of the Blackcurrant available from nurseries that are not alternate hosts of this fungal rust, and are a better choice all around. The Canadian Gooseberry (Ribes oxyacanthoides) is also susceptible to the rust. Red Currants and most other Gooseberries have been found to not be a significant host for the rust, and are safe to plant, but it may not be legal where you live - you need to check local laws. Nurseries should be able to tell you.

If you are buying them from a nursery, buy at the very least two bushes, as they produce better if they can cross pollinate. By cloning, the fruit will be the same as the mother shrub. From seeds, you never get an exact copy of course, so keep that in mind when deciding what route to take.

Transplanting: If you do find some to transplant from the wild, make sure you do it in the late fall or early spring, and plant the tree in the same conditions (light and soil) that they came from. These plants do better if you plant them where the air is not still, so don't plant between two buildings where the air is not moving.

If you buy shrubs, they could be bare root, or in containers. Either way, follow the instructions that come with them - each species and cultivar can have slightly different requirements. Keep lots of air between the bushes to prevent diseases between them, 1.5 meters (5 feet) is good. You will need at least two of any kind.

Seeds: If you are going to plant from seed, I have to warn you, it takes a long time to get the shrub from seed, and the seeds require long stratification times - three to four months, and will produce fruit in the second or third year at the earliest.

Cuttings:If you already have some bushes, you should be able to clone the branches to produce more bushes that will fruit quickly. You can clone by taking 30 cm (1 foot) or so long branch sections (cut off the tip), after the leaves have fallen in the fall, or well before they come out in the spring. Push them about halfway down in damp soil, and keep it damp until you are sure it has rooted and is growing well. The other way that can be done while the plant is in growing season is layering. That is, to bend over a branch, cover part of it with soil and hold it down with a rock or stake, and wait until the part in the soil roots - works much faster if you keep the soil damp where the branch is buried - also make sure a leaf node is part of the branch buried. Once it has rooted well, cut it off from the lower part of the branch and transplant the new bush to where you want it.

Soil & Site: If you are transplanting from the wild, try to identify which one you have, and plant in a spot that is as close to the ideal habitat as possible. There are a few listed below with included habitat information. If buying, follow the recommendations given to you by the nursery. Make sure before you buy, you know what options you have as far as the site goes - this will help the nursery staff give you the best ideas of what to choose.

Maintenance: They do require pruning of about a third of the oldest branches each year to keep the shrub healthy and producing well. Do not put lime on them, as most prefer slightly acidic soil. You will have to fertilize with either composted manure or composted plant material to keep a good harvest up year after year. Keep the ground around them mulched - especially when newly planted, and the first year after planting, don't let them dry out.

Care and pruning of these is straight forward. After they are established where you want them by whatever way you get them there, you want to maintain a program each year of removing any branches older than three years old. Prune in the spring, and each branch you prune, leave about 2.5 cm (1 inch) of branch stub. The older branches are thicker, and have a peeling grey bark on them - it is obvious which ones are older. You also don't want a densely branched shrub, it must be open enough to allow it to let air pass through reducing the risk of mildew diseases. Also, keep the branches from getting longer than a meter (3 feet) so they stay upright. If there are any horizontal branches that are close to, or touching the ground, take them off as well. This will also reduce the chance of mold diseases. When you get it right, from any angle, the shrub should have a V shape, and all the branches upright with some breathing space between them. In the summer cut back side branches to a half dozen leaves, and trim back any that get too tall again.

This is one of those groups where I recommend buying from a nursery. If you do find local ones you like, and want to clone or transplant them, below are descriptions of the most common ones you will find in Eastern North America to help you understand them and the conditions they like .

Wild Black Currant

Wild Black Currant (Ribes americanum), also called: American Black Currant & Eastern Black Currant. The Wild Black Current is good raw and cooked into jams or pies.

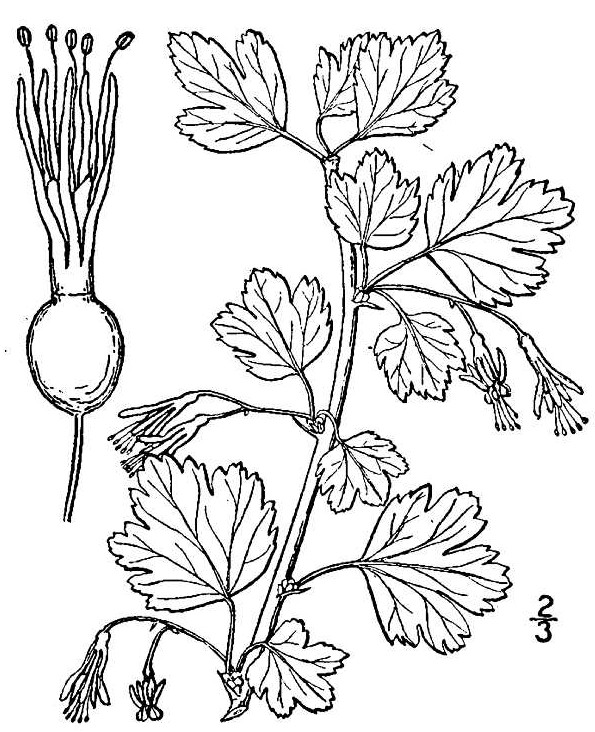

Wild Black Currants are found almost everywhere east of the Rocky Mountains except in the deep southern states of the USA. The leaves are alternate on the branch. The flower/berry clusters come from the same spot on the branch as the leaves do. Sometimes, there seems to be one leave coming out from the branch on each spot where the leaf stem meets it, sometimes, there is a small cluster of leaves coming from where the leaves and berries attach to the stem, sometimes there will be a new stem from the attachment point that produces a few alternate leaves. I think what is happening, is that on the young branches (reddish green with a white bloom) only one leaf is produced at each alternate leaf stem attaching point. On the older, woody branches (reddish brown with most bloom gone) where the leafs and flower clusters attach, there is usually a few leaves - but not compound leaves, a few single leaves meeting at the same point on the branch. On very mature branches, there are vertical splits in the bark that peels back in long oval shapes. Even in the older branches, there is still a noticeable bit a whitish bloom on the reddish, brown bark.

To me, the leaves look a little like Maple leaves with three to five lobes. They are a green to yellow-green with a semi-matte, semi-gloss upper surface. What stands out for me with these leaves is how prominent the leaf veins are on the top of the leaf - you really notice them as they are lower than the rest of the upper surface - like tiny river channels. The underside has very small dull yellow to gold dots (glands actually). The dots are on the top of the leaf, but less obvious. The leaves are variable in their margin (edge), some with deeper lobes. On some, the (single or double) sawtooth margins have a rounded appearance, while some are sharper looking. The stems are finely hairy, as are the leaves, mostly noticeable at the margins.

The round, black berries hang in clusters off a single stem, and are about 6-9mm (1/4 to 1/3 inches) in diameter. When the berries are not fully ripe, they have a deep reddish hue to them.

If you find some in the wild, you should have no trouble starting it by seed, cloning or transplanting. You probably would have difficulty finding it at nurseries, as they tend to carry cultivars of the European version of this shrub, the Blackcurrant (Ribes nigrum), although some of the cultivars may have this one as one of the ancestors.

Description:

- USDA Plant Hardiness Zone: 2-6 (More information on hardiness zones).

- Soil pH: 5.0-7.8

- Plant Size: Shrub up to 1.5 meters (5 feet) high, forms thickets

- Duration: Perennial, lives years

- Leaf Shape: Three to five lobes, more or less similar overall outline to a Sugar Maple leaf, but the margins are quite different

- Leaf Phyllotaxis (Arrangement) on branch: Alternate

- Leaf Size: 3.8-9 cm (1 1/2 to 3 1/2 inches) long and wide

- Leaf Margin: Course, irregular Serrated (saw toothed edge)

- Leaf Notes: The leaf surface is wrinkled from sunken veins, and the bottom of the leaf is hairy along the veins, with some hairs between veins. The bottom of the leaf is paler green than the upper side. Upper and lower surface of the leaves are covered with small gold colored dots

- Flowers: An inflorescence that is a raceme with up to 15 white to greenish flowers

- Fruit: Black, smooth skinned about 6-9mm (1/4 to 1/3 inches) in diameter

- Bark: Near base of shrub, the bark of mature branches are reddish black to reddish brown with white lenticels (checking), younger and upper branches are grey with light brown ridges that are woody in texture

- Habitat: Variety of habitats, undisturbed, moist, open woodlands near water are its favorite, but will grow in boggy areas in conifer forests, right by marshlands. Can tolerate a lot of shade.

Web Resources:

- Pictures of the Wild Black Currant on the web here (Google images) and here (Bing images).

- Interactive USDA distribution map and plant profile here.

- The Biota of North America Program (BONAP) distribution map here. BONAP map color key here.

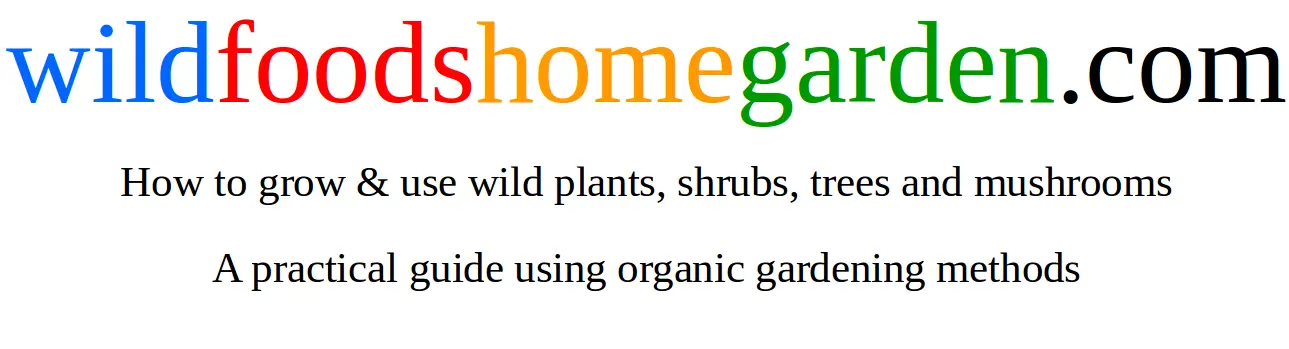

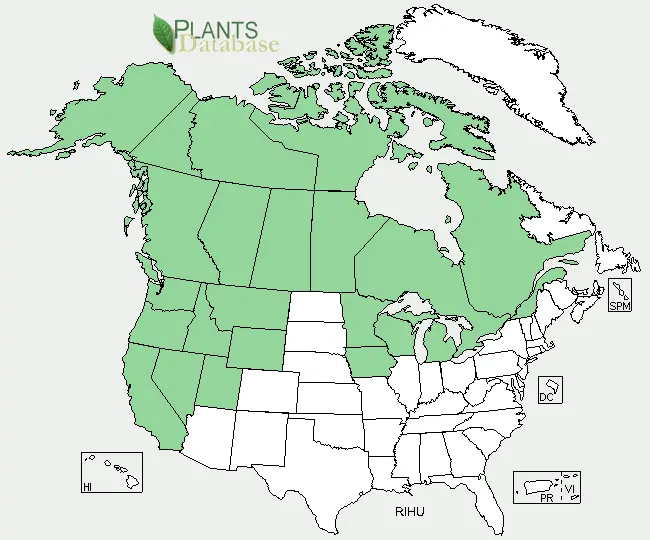

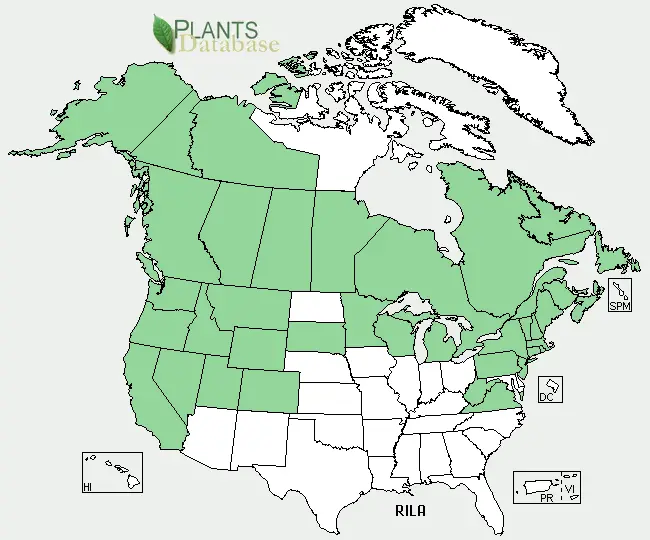

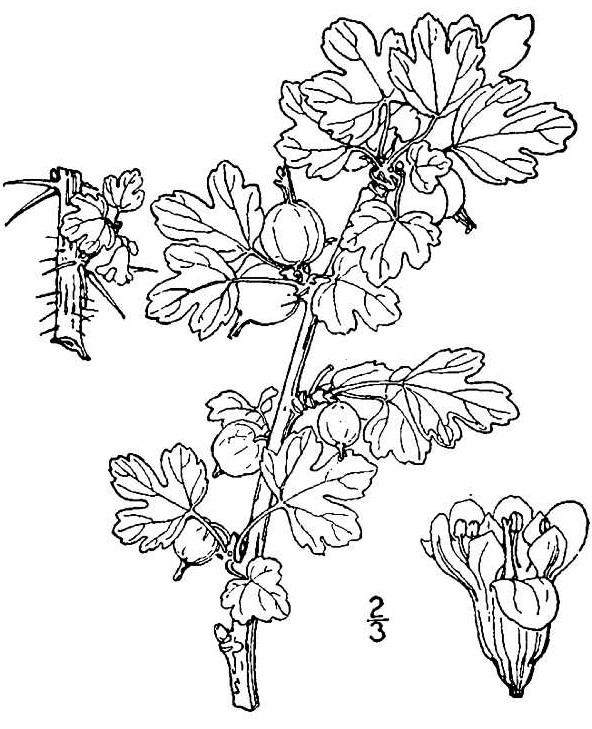

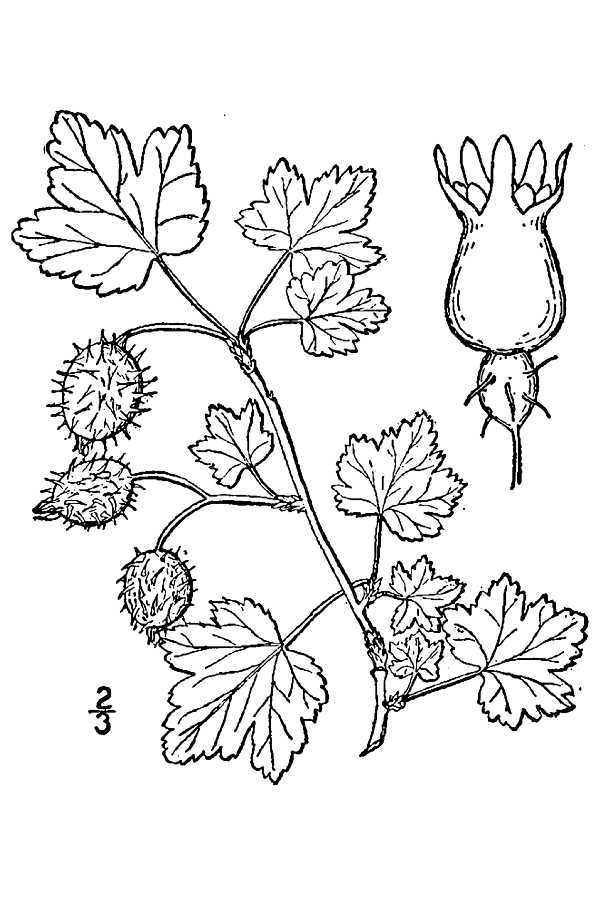

Wild Black Currant (Ribes americanum) range. Distribution map courtesy of U. S. Department of Agriculture (USDA Natural Resources Service) and used in accordance with their policies.

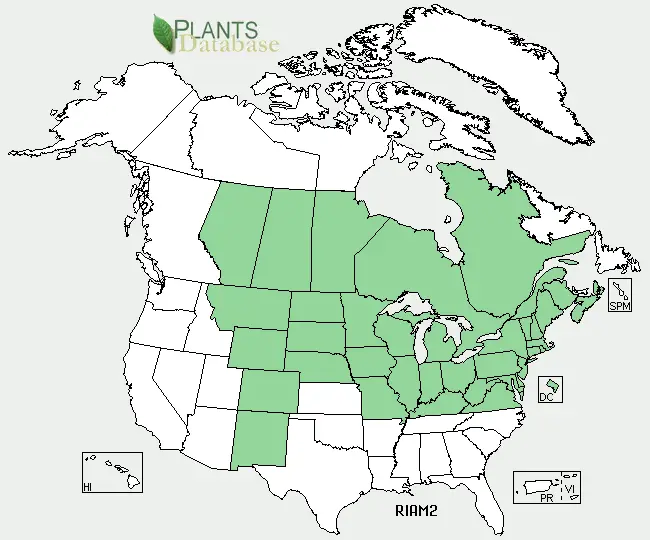

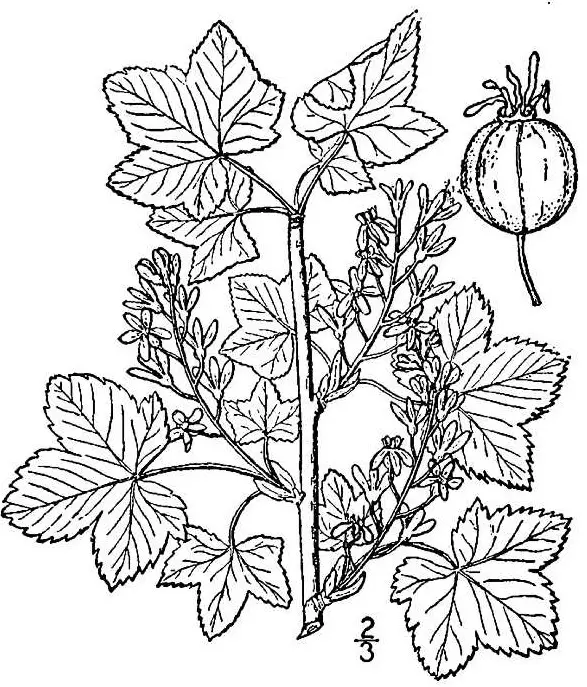

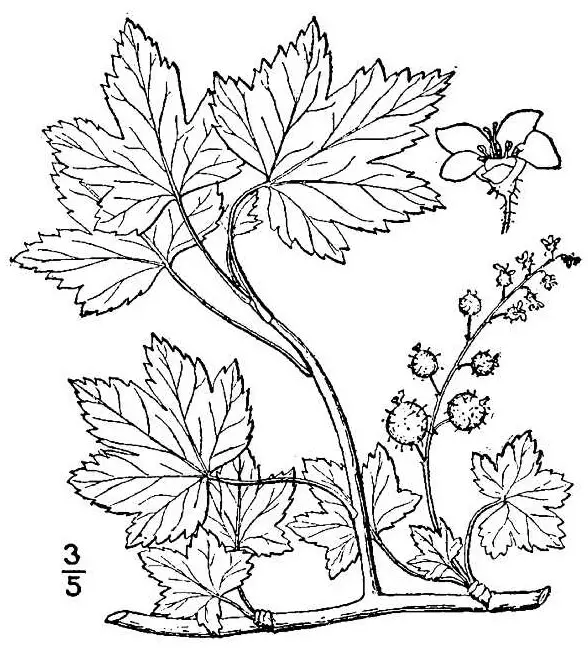

Wild Black Currant (Ribes americanum) drawing. (USDA-NRCS PLANTS Database / Britton, N.L., and A. Brown. 1913. An illustrated flora of the northern United States, Canada and the British Possessions. 3 vols. Charles Scribner's Sons, New York. Vol. 2: 238.)

Wild Black Currant (Ribes americanum) leaves in fall. (By: Nadiatalent CC BY-SA 3.0)

European Blackcurrant

European Blackcurrant (Ribes nigrum). Although native to Europe, this plant has naturalized in parts of North America, so you may find it in the wild. There are many cultivars and crosses with this plant so the description will cover the range.

There are many cultivars available at nurseries for this shrub, and you should have no trouble finding one that is selected for your area that is resistant to the White Pine Blister Rust (Cronartium ribicola) as an alternate host. I suggest not making clones from shrubs found in the wild or trying to grow it from seed. It may be one that is not a cultivar resistant to the White Pine Blister Rust, and you would be putting White Pine trees at risk in your local area, plus the leaves of the Blackcurrant would become infected with the rust. Best to buy one of these selected to not be susceptible.

Description:

- USDA Plant Hardiness Zone: 2-7 (More information on hardiness zones).

- Soil pH: 4.8-7.0 (Best is 6.0-6.5)

- Plant Size: 1.5 meters (5 feet) tall

- Duration: Perennial Shrub that lives many years by sending new branches from the roots each year, and self renewing

- Leaf Shape: Three to five lobes, more or less similar overall outline to a Sugar Maple leaf, but the margins are quite different

- Leaf Phyllotaxis (Arrangement) on branch: Alternate

- Leaf Size: 3 to 5 cm (1 1/5 to 2 inches) long and wide

- Leaf Margin: Course, irregular Serrated (saw toothed edge)

- Leaf Notes: The leaf surface is wrinkled from sunken veins

- Flowers: 8 cm (3 in) long raceme with ten to twenty flowers that are light to strong pink with five petals each

- Fruit: Ripe starting in July, at first fruit is green, when ripe turns a dark purple to black, up to 1 cm (2/5 inch) diameter

- Bark: Hairless, fresh growth is green turning slight reddish brown to grey to a very slight yellowish hue

- Habitat: Can tolerate a wide variety of conditions, but does prefer rich, moist soil near water and slightly acidic soils. Not keen on growing on hard clay.

Web Resources:

- Pictures on the web here (Google images) and here (Bing images).

- Interactive USDA distribution map and plant profile here.

- The Biota of North America Program (BONAP) distribution map here. BONAP map color key here.

European Blackcurrant (Ribes nigrum) range. Distribution map courtesy of U. S. Department of Agriculture (USDA Natural Resources Service) and used in accordance with their policies.

European Blackcurrant (Ribes nigrum) Illustration. (By: Carl Axel Magnus Lindman)

.jpg)

European Blackcurrant (Ribes nigrum). (By: Rasbak GNU Free Documentation License, Version 1.2)

European Blackcurrant (Ribes nigrum) flowers and unripe fruit. (By: H. Zell GNU Free Documentation License, Version 1.2)

European Blackcurrant (Ribes nigrum) ripe fruit and leaves. (By: Jerzy Opioła GNU Free Documentation License, Version 1.2)

European Blackcurrant (Ribes nigrum) whole plant in field. (By: Thue)

Northern Black Currant

Northern Black Currant (Ribes hudsonianum). This Currant is bitter tasting, and not worth collecting. Found in shaded, moist highland areas, and shaded areas that are always wet, but rivers, streams, wetlands. The only reason I've included here, is that the fruit looks like one of the Black Currants, and so you should know it to avoid it. Not poisonous as far as I am aware.

I find it odd that this is listed as an edible fruit by some sources. Either the plant is quite variable due to conditions (does happen with some plants), and in some areas it is not awful tasting, or there are subspecies of this one and each has their own taste, or, as I most likely suspect, people get this confused with the "Wild Black Currant", or it could just be that people have never tried some for themselves and copied bad information. Whatever the reason, I won't eat them, they are bitter and poor tasting.

Don't bother growing this plant in your home garden. There are far better choices.

Description:

- USDA Plant Hardiness Zone: No data, but lives in very cold northern areas (More information on hardiness zones).

- Soil pH: 3.4-7.7

- Plant Size: Up to 1.5 meters (5 feet) or slightly more

- Duration: Perennial Shrub

- Leaf Shape: Three lobed (sometimes five) maple-like leaf

- Leaf Phyllotaxis (Arrangement) on branch:

- Leaf Size: 10 cm (4 inches) wide and long

- Leaf Margin: coarsely Serrated (saw toothed edge)

- Leaf Notes: Strong, unpleasant smell, underside of leaf in hairy

- Flowers: 5 petalled, up to 50 flowers per raceme, upright - not drooping or hanging from stem

- Fruit: Unripe: green, ripe: black, bitter, I do not consider edible due to taste

- Bark: Branches have shiny yellow resin glands that look like dots, no spines

- Habitat: Shaded wet area, often in high elevations

Web Resources:

- Pictures on the web here (Google images) and here (Bing images).

- Interactive USDA distribution map and plant profile here.

- The Biota of North America Program (BONAP) distribution map here. BONAP map color key here.

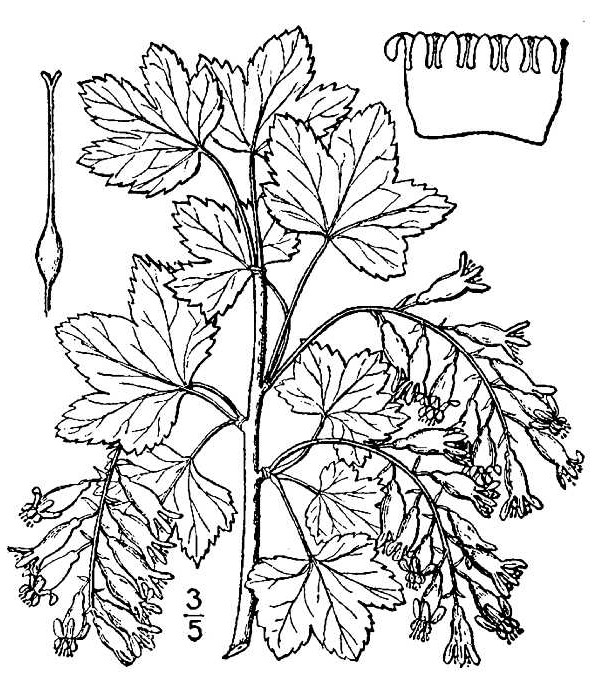

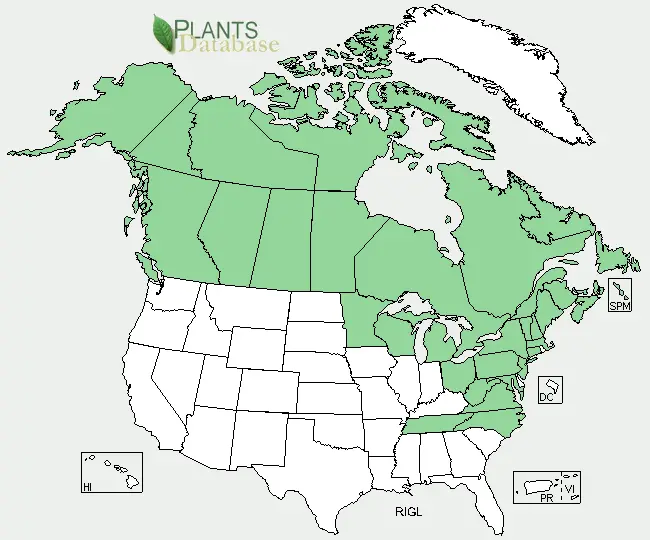

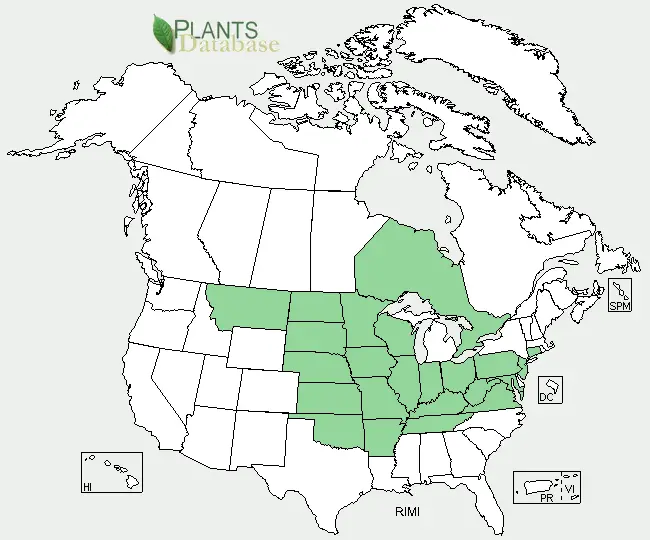

Northern Black Currant. (Ribes hudsonianum) range. Distribution map courtesy of U. S. Department of Agriculture (USDA Natural Resources Service) and used in accordance with their policies.

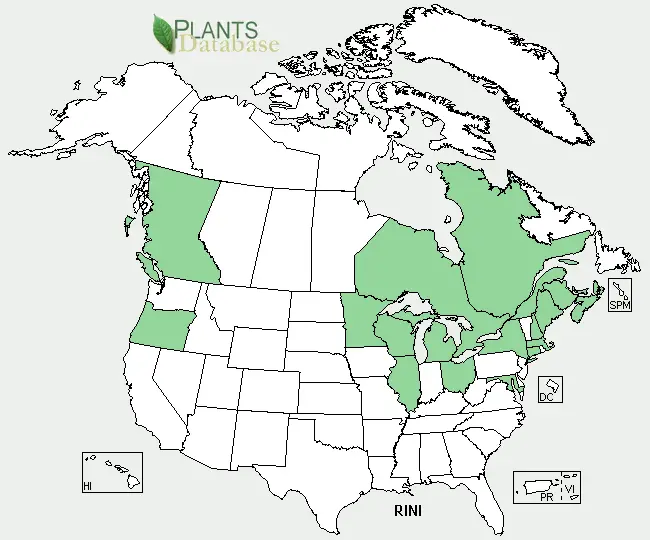

Northern Black Currant. (Ribes hudsonianum) drawing. (USDA-NRCS PLANTS Database / Britton, N.L., and A. Brown. 1913. An illustrated flora of the northern United States, Canada and the British Possessions. 3 vols. Charles Scribner's Sons, New York. Vol. 2: 237. )

Northern Black Currant. (Ribes hudsonianum) in flower. (Joe F. Duft, hosted by the USDA-NRCS PLANTS Database / USDA NRCS. 1992. Western wetland flora: Field office guide to plant species. West Region, Sacramento.)

Red Currant

Red Currant (Ribes triste). Known also as Swamp Red Currant, Wild Red Currant and Northern Red Currant. Often the Red Currant part of the name in any of the names is spelled as one word - Redcurrant. Too sour to eat raw except for a few if you like tart flavors, but can be used for making jams, jellies and for other baking or cooking where fruit is called for. Berries are a bright red to orange tinted red. Shiny, almost translucent appearance - very nice looking berries.

If you live where the conditions are right, you will have no problem growing this plant. It roots very easily from cut branches, so the best way is to cut some branches that you find in the wild (nip off the very top), put in water in a container to take home and push right in the wet ground. It must stay wet all the time until established, and best to stay wet most or all the time after. Best to do this after the leaves have dropped in the fall or before leaves have come out in the spring.

Description:

- USDA Plant Hardiness Zone: down to zone 2 (More information on hardiness zones).

- Soil pH: 5.0-7.5

- Plant Size: Up to 1 meter (3 feet) high Shrub

- Duration: Perennial Shrub

- Leaf Shape: Very similar to the Wild Black Currant leaf, which is a three to five lobed leaf that looks similar in basic shape to the Sugar Maple leaf (especially when five lobed). See drawing for the Wild Black Currant leaf.

- Leaf Phyllotaxis (Arrangement) on branch: Alternate

- Leaf Size: Up to 10 cm (4 inches) long and wide

- Leaf Margin: Coarsely Serrated (saw toothed edge)

- Leaf Notes: Does not have the small gold dots on leaf that the Wild Black Currant leaves have

- Flowers: 4-10 cm (1 1/2 to 4 inches) long racemes (clusters) of five petalled (petal-like calyx technically) pinkish-purple to salmon colored flowers. The "petals" are curled back. There are 6 to 15 flowers per cluster. Flowers in May to June.

- Fruit: 6-9 mm diameter bright red to orange hued red, shiny and smooth skinned. Ripe in July to August

- Bark: Grey and hairless

- Habitat: Cool, wet to moist areas. By water in acidic conditions in boreal forest areas.

Web Resources:

- Pictures of the Red Currant on the web here (Google images) and here (Bing images).

- Interactive USDA distribution map and plant profile here.

- The Biota of North America Program (BONAP) distribution map here. BONAP map color key here.

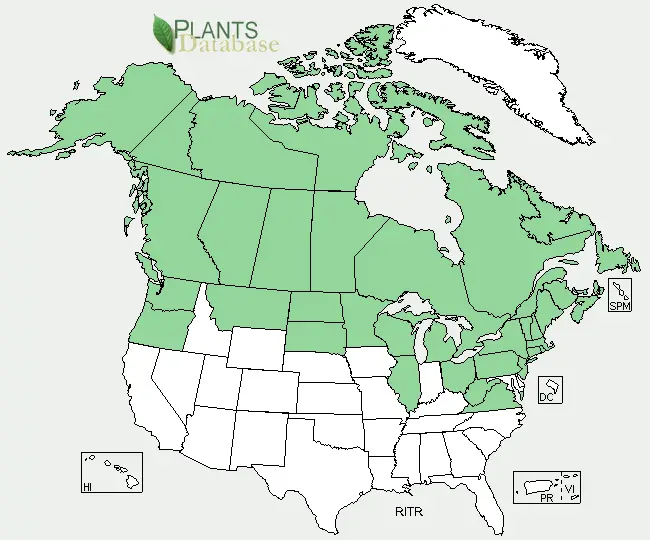

Red Currant (Ribes triste) range. Distribution map courtesy of U. S. Department of Agriculture (USDA Natural Resources Service) and used in accordance with their policies.

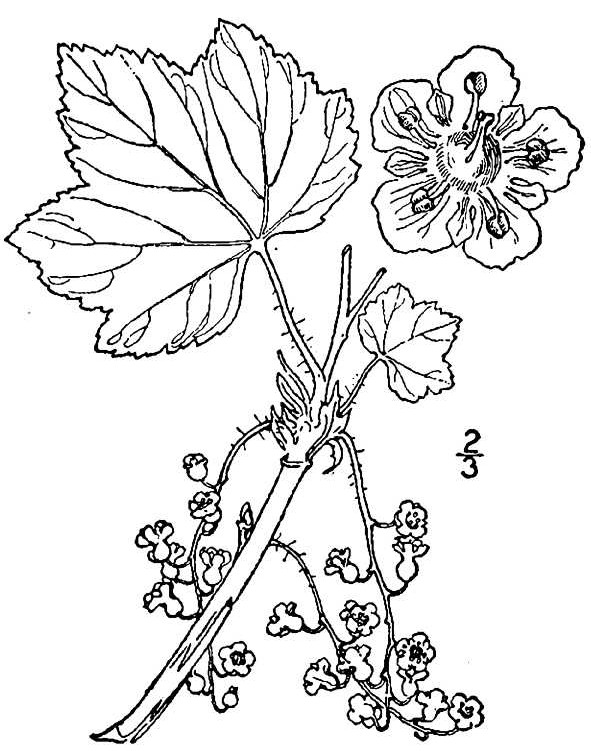

Red Currant (Ribes triste) drawing. (USDA-NRCS PLANTS Database / Britton, N.L., and A. Brown. 1913. An illustrated flora of the northern United States, Canada and the British Possessions. 3 vols. Charles Scribner's Sons, New York. Vol. 2: 237.)

.jpg)

Red Currant (Ribes triste) leaves. (By: Superior National Forest Attribution 2.0 Generic)

.jpg)

Red Currant (Ribes triste) flowers (By: Superior National Forest Attribution 2.0 Generic)

Swamp Black Currant or Prickly Currant

Swamp Black Currant or Prickly Currant (Ribes lacustre), also called Swamp Gooseberry, Black Gooseberry. This one has the prickles on the branches of a Gooseberry, but the large number of flowers per cluster of a Currant. It has deep lobed leaves, and the stems, branches and berries are covered in sharp, hair like thorns or prickles that can be painful if they stab you when handling the plant. They give the branches a fuzzy, light auburn reddish look when you see them from a distance. Remember, Poison Ivy vines that are climbing other trees and shrubs can have the same auburn reddish fuzzy look, and likes to grow right where these do. The berries, though not poisonous, are dull to nasty tasting and not worth the effort, especially considering the nasty prickles of the plant. Funny thing about these is the reports of how they taste vary quite a bit. Could be local variations - it does happen. In Ontario, they don't taste good at all, and most other reports from Ontario back that up. There is one report on the web that is repeated site, after site, word for word, that the crushed berries smell bad but taste good. I agree with the smell bad part. Berries tend to be in one's or two's - red and green when immature, black and shiny with soft prickles when mature. Just looking at the berry makes you think it's not a good idea to put it in your mouth raw, although some do eat them raw. If you do choose to try eating this one, cook them in some water, then strain them through a sieve after, then use the strained liquid as a base for a jam or jelly. Remember, even after this work, the taste is dull to unpleasant - there definitely are better ones.

Between the sharp, painful stabs the hair like thorns on the branches can give and the dull to poor taste of the fruit, I cannot see why you would want to grow them, other than the flowers are very nice looking.

Description:

- USDA Plant Hardiness Zone: Sources of unknown origin say down to zone 0, but not able to verify (More information on hardiness zones).

- Soil pH: 4.0-8.0 (not able to confirm with multiple sources)

- Plant Size: Up to 2 meters (6 1/2 feet) high

- Duration: Perennial Shrub

- Leaf Shape: Deep lobed maple-like leaves

- Leaf Phyllotaxis (Arrangement) on branch: Alternate

- Leaf Size: Up to 7.5 cm (3 inches) long and 6 cm (2 2/5 inch) wide

- Leaf Margin: Deep, course Serrated (saw toothed edge)

- Leaf Notes: Lighter green, quite often yellowish green

- Flowers: Five petalled, two toned (light pink outer edges, darker maroon red inside), multiple flowers per cluster

- Fruit: 6-8 mm long dark purple berries covered with weak spines, or prickles, unpleasant smell

- Bark: Covered in Auburn red prickles or hair like thorns

- Habitat: Wet or swampy areas, more common in higher elevations

Web Resources:

- Pictures of the Swamp Black Currant on the web here (Google images) and here (Bing images).

- Interactive USDA distribution map and plant profile here.

- The Biota of North America Program (BONAP) distribution map here. BONAP map color key here.

Swamp Black Currant (Ribes lacustre) range. Distribution map courtesy of U. S. Department of Agriculture (USDA Natural Resources Service) and used in accordance with their policies.

Swamp Black Currant (Ribes lacustre) drawing. (USDA-NRCS PLANTS Database / Britton, N.L., and A. Brown. 1913. An illustrated flora of the northern United States, Canada and the British Possessions. 3 vols. Charles Scribner's Sons, New York. Vol. 2: 236.)

Swamp Black Currant (Ribes lacustre) in flower. Note how the flower clusters hang from branch. (By: Walter Siegmund GNU Free Documentation License, Version 1.2)

Swamp Black Currant (Ribes lacustre) flowers in close. (By: Walter Siegmund GNU Free Documentation License, Version 1.2)

Swamp Black Currant (Ribes lacustre) fruit. Note prickles on fruit. (By: Walter Siegmund GNU Free Documentation License, Version 1.2)

Swamp Black Currant (Ribes lacustre). Note how nasty those prickles are on the branches. This is a hazardous plant to deal with. (By: Walter Siegmund GNU Free Documentation License, Version 1.2)

Skunk Currant

Skunk Currant (Ribes glandulosum). Only the red berries have hairs with this one, and although I have read the berries have been used as food, the taste is poor and they are covered with spiky hairs, you would have to cook and strain them to be rid of the spikes. The name "Skunk Currant" comes from the smell when you crush a leaf. I have read about, but not tasted a light pink to whitish version of this one that supposedly tastes good.

I'm sure you could grow these, but there are much better choices.

Description:

- USDA Plant Hardiness Zone: down to zone 2 (More information on hardiness zones).

- Soil pH: 6.0-7.5

- Plant Size: Up to 1 meter (3 feet) tall.

- Duration: Perennial Shrub

- Leaf Shape: Very Maple like, five to seven lobed

- Leaf Phyllotaxis (Arrangement) on branch:

- Leaf Size: Up to 8 cm (3 inches) long

- Leaf Margin: Coarsely Serrated (saw toothed edge)

- Leaf Notes: Leaves emit a skunk like smell when crushed

- Flowers: Five white petalled flowers in clusters of a couple to over 10

- Fruit: Bright red with spikey hairs, green and red when unripe

- Bark: No spikes or spines

- Habitat: Damp areas in partial shade and boreal forest openings

Web Resources:

- Pictures of the Skunk Currant on the web here (Google images) and here (Bing images).

- Interactive USDA distribution map and plant profile here.

- The Biota of North America Program (BONAP) distribution map here. BONAP map color key here.

Skunk Currant (Ribes glandulosum) range. Distribution map courtesy of U. S. Department of Agriculture (USDA Natural Resources Service) and used in accordance with their policies.

Skunk Currant (Ribes glandulosum) drawing. (USDA-NRCS PLANTS Database / Britton, N.L., and A. Brown. 1913. An illustrated flora of the northern United States, Canada and the British Possessions. 3 vols. Charles Scribner's Sons, New York. Vol. 2: 238.)

Skunk Currant (Ribes glandulosum) plant in flower. (Mark A. Garland, hosted by the USDA-NRCS PLANTS Database)

Skunk Currant (Ribes glandulosum) leaves. (Mark A. Garland, hosted by the USDA-NRCS PLANTS Database)

Skunk Currant (Ribes glandulosum) flowers up close. (Mark A. Garland, hosted by the USDA-NRCS PLANTS Database)

Canadian Gooseberry

Canadian Gooseberry (Ribes oxyacanthoides).

Because this one can be an alternate host for White Pine Blister Rust (Cronartium ribicola), in many places it is rare, as it has been intentionally eradicated. Also, the taste of the fruit raw is not the greatest, but you can eat it. Cooked and made into jams or jellies is about the best thing you can do with it. There are other Gooseberries that are better for this as well though. The most likely places you will find this in Eastern North America is in openings in conifer forests in low areas near water of some kind, rivers, streams, marshlands, etc. It has nasty prickles along the stems, and big thorns right near the leaf axils, so be careful when working around this plant.

When describing the leaves of most plants in the Ribes Genus, I say "maple" leaf like. This one does have the basic 3-5 lobed simple leaf like the others, but the leaf on this plant reminds me more of a common grocery store Geranium leaf. The Geranium with the big compound pink or red flower heads (Pelargonium).

I suggest not growing this one. For one thing it is an alternate host for White Pine Blister Rust (Cronartium ribicola). Also, the fruit, though edible, is not as good as others. Plus, the thorns and prickles are quite sharp and nasty and could injure you while pruning and picking, or injure pets.

Description:

- USDA Plant Hardiness Zone: 3-8 (More information on hardiness zones).

- Soil pH: no data, but as it is associated with both conifer and mixed forest regions, as reasonable guess is slightly acidic to neutral

- Plant Size: Up to 1.5 meters (5 feet) tall

- Duration: Perennial Shrub

- Leaf Shape: 3-5 rounded lobes, some are shallow lobed, some deeper. Maple like, but very rounded on lobes

- Leaf Phyllotaxis (Arrangement) on branch: Alternate

- Leaf Size: 1-4 cm (2/5 to 1 3/5 inches) wide and long

- Leaf Margin: large Serrated (saw toothed edge) for leaf size, often the serrations are rounded on their tips, sometimes pointy

- Leaf Notes: Red in fall

- Flowers: 5-6 petalled, white to light pink, with long tube section between petals and stem, 1-3 flowers per leaf node

- Fruit: Red Grape color to blackish, usually with long tube like flower still attached to end, but dried up and brown. Bright green when immature. Ripe, usually between 10-15 mm diameter. Single to group of three. Many seeds per Gooseberry

- Bark: Grey to reddish covered with prickles and thorns near leaf nodes

- Habitat: Associated with conifers especially near water ways such as rivers and streams. Tends to be in low lying areas.

Web Resources:

- Pictures on the web here (Google images) and here (Bing images).

- Interactive USDA distribution map and plant profile here.

- The Biota of North America Program (BONAP) distribution map here. BONAP map color key here.

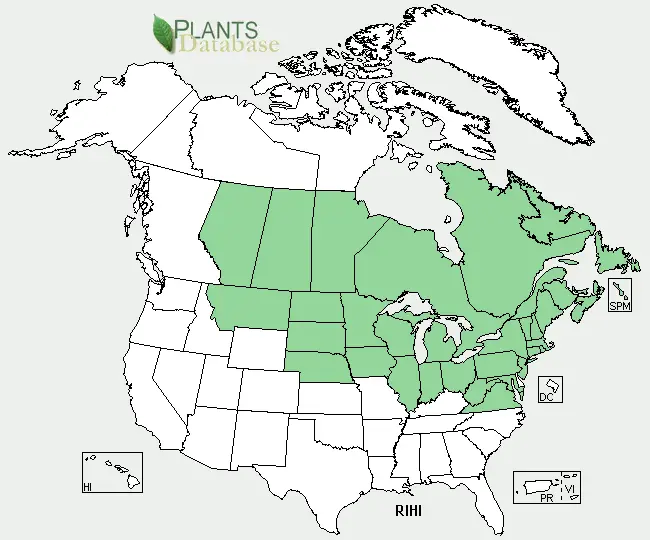

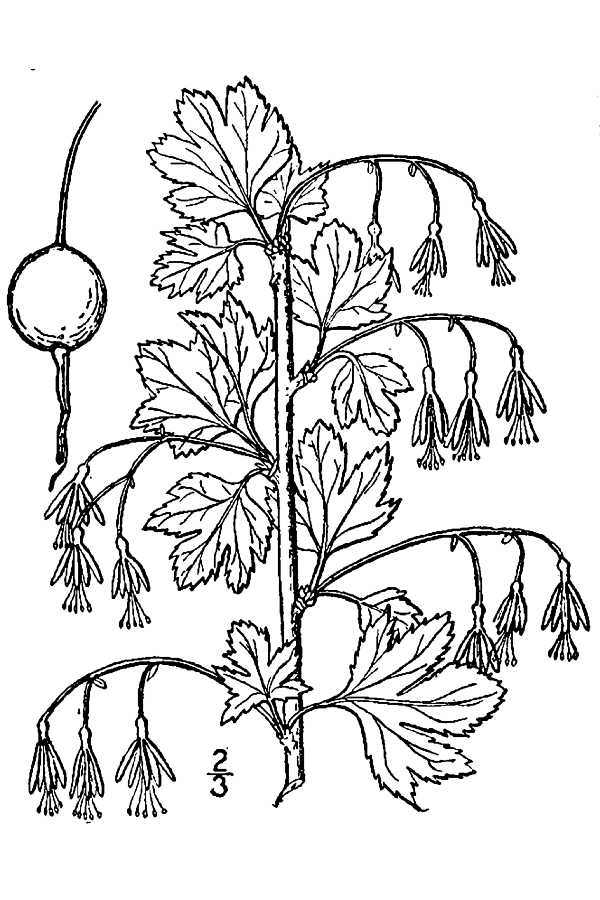

Canadian Gooseberry (Ribes oxyacanthoides) range. Distribution map courtesy of U. S. Department of Agriculture (USDA Natural Resources Service) and used in accordance with their policies.

Canadian Gooseberry (Ribes oxyacanthoides) drawing. (USDA-NRCS PLANTS Database / Britton, N.L., and A. Brown. 1913. An illustrated flora of the northern United States, Canada and the British Possessions. 3 vols. Charles Scribner's Sons, New York. Vol. 2: 240. )

American Gooseberry

American Gooseberry (Ribes hirtellum). Known also as the Hairy-stem Gooseberry, Hairy Gooseberry, Wedge-leaf Gooseberry, Northern Gooseberry, Swamp Gooseberry, Smooth Gooseberry, Wild Gooseberry. How could it be known as the Hairy Gooseberry and the Smooth Gooseberry? The young twigs can be smooth or with scattered fine hair-like prickles that fall off with the first year bark, leaving a smooth bark.

This is one of the better tasting Gooseberries, raw or cooked, that is native to Eastern North America. And, as a bonus, although the stems are hairy, they do not have the nasty sharp prickles and thorns of the Canadian Gooseberry. Nice snack when fresh, and makes tasty jams, jellies, and pies. Since ripe ones are often green (although can be red-grape red color as well), it is easy to pick a "green" one thinking it is ripe. The taste will be sour, but still edible. They get their sweet/sour combination when they turn ripe. The sour part is the ascorbic acid (vitamin C), which they are very high in. The unripe ones are a darker green, while the riper ones have a yellowish green color. Hard to tell unless you see both on a plant and can compare by tasting.

Like most members of this Genus, they are fairly easy to clone by cuttings or layering. If you are going to buy from a nursery, the most common Gooseberry you will find will be a cross of this one and the European Ribes uva-crispa.

Description:

- USDA Plant Hardiness Zone: 3-8 (More information on hardiness zones).

- Soil pH: 6.2-6.5

- Plant Size: Up to 1 meter, (3 feet) tall

- Duration: Perennial Shrub

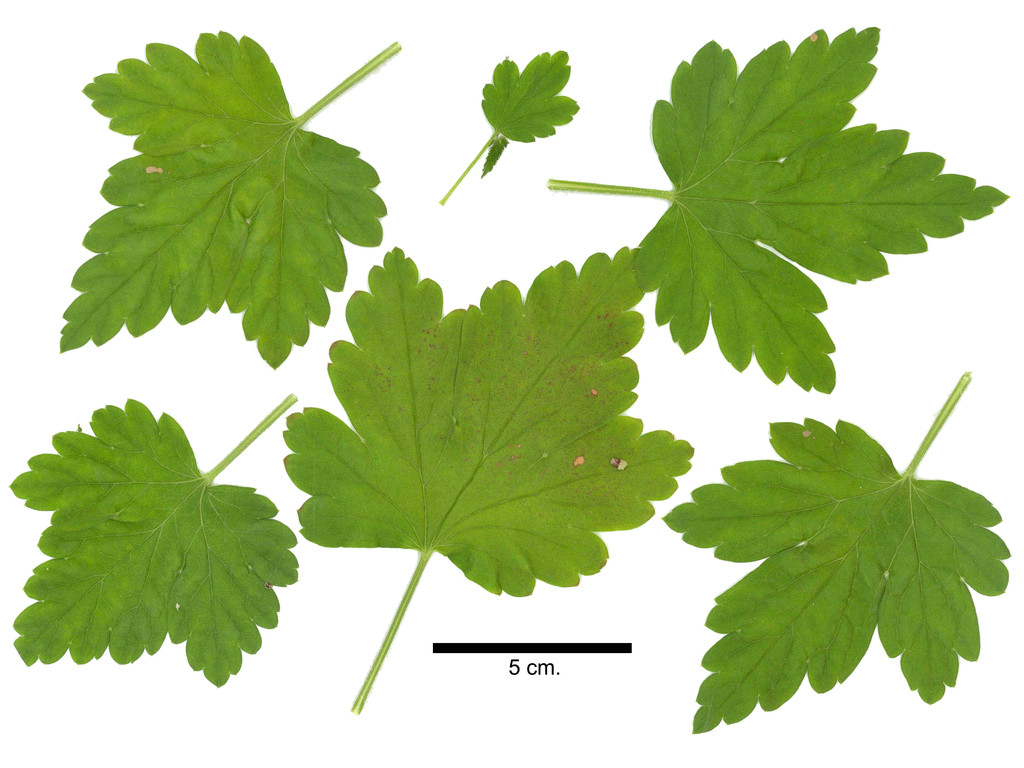

- Leaf Shape: 3-5 lobed maple leaf like

- Leaf Phyllotaxis (Arrangement) on branch: Alternate

- Leaf Size: 2.5-6 cm (1 to 2 1/3 inches)long and wide

- Leaf Margin: Irregular, coarse, Serrated (saw toothed edge)

- Leaf Notes: If growing in acidic soils, leaf undersides tend to have little hair, if in more alkaline soils, the leaves are hairier

- Flowers: 5 petalled, green and purplish red, to yellowish in singles or small clusters on short stems

- Fruit: 8-12 mm diameter, ranging from green to a purple black (often have the color of red grapes)

- Bark: Light grey, can be smooth or with hairs that fall off with bark after first year leaving smooth bark behind.

- Habitat: By water, in damp areas in forest clearings or open woods.

Web Resources:

- Pictures on the web here (Google images) and here (Bing images).

- Interactive USDA distribution map and plant profile here.

- The Biota of North America Program (BONAP) distribution map here. BONAP map color key here.

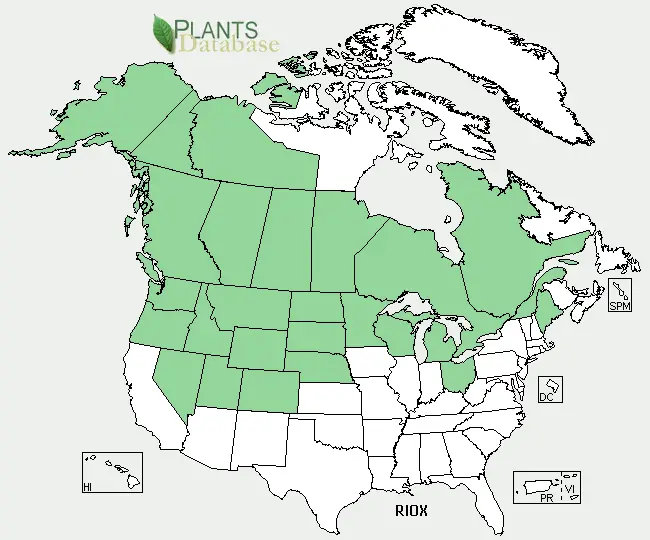

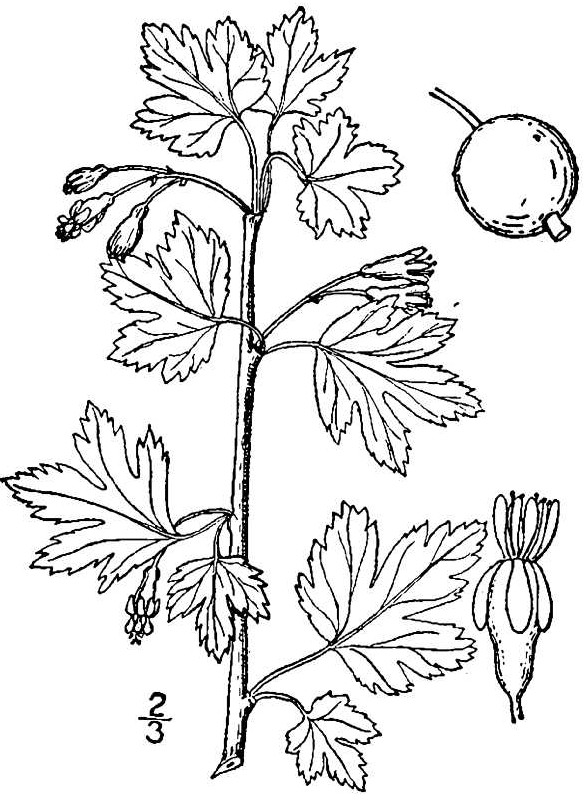

American Gooseberry (Ribes hirtellum) range. Distribution map courtesy of U. S. Department of Agriculture (USDA Natural Resources Service) and used in accordance with their policies.

American Gooseberry (Ribes hirtellum) drawing. (USDA-NRCS PLANTS Database / Britton, N.L., and A. Brown. 1913. An illustrated flora of the northern United States, Canada and the British Possessions. 3 vols. Charles Scribner's Sons, New York. Vol. 2: 241.)

American Gooseberry (Ribes hirtellum) leaves. (By: Nadiatalent CC BY-SA 3.0)

American Gooseberry (Ribes hirtellum) flower. (By: Nadiatalent CC BY-SA 3.0)

American Gooseberry (Ribes hirtellum) (By: Nadiatalent Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license)

American Gooseberry (Ribes hirtellum) fall colors. (By: Daderot Creative Commons CC0 1.0 Universal Public Domain Dedication)

Eastern Prickly Gooseberry

Eastern Prickly Gooseberry (Ribes cynosbati). Known also as the Dogberry and Pasture Gooseberry.

If you are in a mixed or conifer forest, or in open land around the same, not right by water, and come across a Gooseberry that is the color of a red Grape, but is covered with soft prickles, while the branches have very few prickles, you probably have this one. Tends to do better in drier areas than most in this Genus, and although the fruit looks dangerous, it is not, and the taste, though not the very best, is not bad at all. Fairly common, so if in the right kinds of areas, expect this to be there.

Not sure about taking cuttings and putting them in the ground like most damp area loving members of this Genus, but might be worth a try - keep the ground damp until you are sure it took. May be best to do layering with this one and keep the soil damp where the layering is taking place. This may be one to start from seed if you have the patience. There is little chance of finding this one at a nursery.

Description:

- USDA Plant Hardiness Zone: down to zone 2 (More information on hardiness zones).

- Soil pH: 6.5-7.5

- Plant Size: 1 meter (3 feet), occasionally a little taller

- Duration: Perennial Shrub

- Leaf Shape: Still maple leaf like overall, it has rounded lobes that give it a "Geranium leaf" look. 3-5 lobed. Up to three leaves per node, but not compound leaves

- Leaf Phyllotaxis (Arrangement) on branch: Alternate

- Leaf Size: 5 cm (2 inches) long and wide

- Leaf Margin: Irregular, large Serrated (saw toothed edge) that is usually Crenate - Crenate means "rounded sawtooth".

- Leaf Notes: Leaf stems are hairy

- Flowers: Occur in late spring, greenish yellow in groups of 1-3. Flowers hang down from branch. Flower stems come from leaf axils. Normally 5 petals, with long tube like center protruding out from where the folded back petals are

- Fruit: Covered in prickles which are soft, so still quite edible, taste is OK. Green when unripe, a reddish purple color when ripe - the color is very much like that of a Red Grape. In groups of 1-3 hanging along the branch from the leaf axils. Small fruit, about 8-9 mm (1/3 inch) diameter.

- Bark: Young green branches have hairs that look very similar to the needles that the Stinging Nettle has. After the first year, the outer bark falls off, leaving a grey and purplish to brown vertically stripy stem with no prickles or hairs, except for a thorn like group of 1-3 prickles at the leaf node. On older branches have short thorns on them not just at the node

- Habitat: In forests in open (not full shade) areas. Not as associated with being by wetlands as some of the others in this Genus. As the "Pasture Berry" name would indicate, this is often on the edges of Pasture like land - more tolerant of drier, full sun conditions than many Gooseberries.

Web Resources:

- Pictures on the web here (Google images) and here (Bing images).

- Interactive USDA distribution map and plant profile here.

- The Biota of North America Program (BONAP) distribution map here. BONAP map color key here.

Eastern Prickly Gooseberry (Ribes cynosbati) range. Distribution map courtesy of U. S. Department of Agriculture (USDA Natural Resources Service) and used in accordance with their policies.

Eastern Prickly Gooseberry (Ribes cynosbati) drawing. (USDA-NRCS PLANTS Database / Britton, N.L., and A. Brown. 1913. An illustrated flora of the northern United States, Canada and the British Possessions. 3 vols. Charles Scribner's Sons, New York. Vol. 2: 239.)

Eastern Prickly Gooseberry (Ribes cynosbati) leaves and young fruit. (By: Nadiatalent CC BY-SA 3.0)

Eastern Prickly Gooseberry (Ribes cynosbati) leaves beginning to turn to fall colors. (By: Nadiatalent CC BY-SA 3.0)

Eastern Prickly Gooseberry (Ribes cynosbati) ripe fruit. (By: Nadiatalent CC BY-SA 3.0)

Missouri Gooseberry or Missouri Currant

Missouri Gooseberry or Missouri Currant (Ribes missouriense). Known also as the Missouri currant.

This one is like the Eastern Prickly Gooseberry in that the color, taste and size of the fruit is about the same, the leaves are basically the same, they both like drier areas, but with one reversal. The branches of this one are covered in prickles (that will stab you), while the fruit is free of any prickles, while the Eastern Prickly Gooseberry has few prickles on the branches but the fruit is covered with soft prickles. Odd how two basically similar plants that like the same places came to have inverted strategies, and both survived.

Not sure about taking cuttings and putting them in the ground like most damp area loving members of this Genus, but might be worth a try - keep the ground damp until you are sure it took. May be best to do layering with this one and keep the soil damp where the layering is taking place. This may be one to start from seed if you have the patience. There is little chance of finding this one at a nursery.

Description:

- USDA Plant Hardiness Zone: 4-7 (More information on hardiness zones).

- Soil pH: 6.0-7.9

- Plant Size: 1.5 meters (5 feet) tall generally

- Duration: Perennial Shrub

- Leaf Shape: Maple leaf like, deep lobes, 3-5 large lobes, leaves occur in groups of 1-3, but not compound leaves - 1-3 simple leaves from the same node.

- Leaf Phyllotaxis (Arrangement) on branch: Alternate

- Leaf Size: Up to 5 cm (2 inches) long and wide

- Leaf Margin: Crenate (Crenate means "rounded sawtooth") edges that are so large they look like small lobes

- Leaf Notes: While the leaf has no or very tiny hairs, the stem of the leaf is hairy

- Flowers: Where the leaf axils are (leaf stems come from branch) there is a group of 1-3 flowers. Flowers hang down. Each flower has 5 (maybe 6 sometimes) whitish with hint of green petals that sometimes have a pinkish tint near the base of the petal. From the center of the flower comes a long thin tube. Petals are usually folded back. Flower is very sparse looking with thin petals, and long thin tube.

- Fruit: Green when unripe, Red Grape reddish to purplish when mature with no prickles on fruit. In hanging groups of 1-3 along the branches. Small fruit, about 8-9 mm (1/3 inch) diameter.

- Bark: Sharp prickles along branches with bigger thorns near the leaf nodes. The prickles will stab and pierce the skin. Bark after first year is light grey.

- Habitat: Dry, open woods, along fence lines, open fields, power line clearings, edges of woods, rocky fields, or where there has been clearing of the trees

Web Resources:

- Pictures on the web here (Google images) and here (Bing images).

- Interactive USDA distribution map and plant profile here.

- The Biota of North America Program (BONAP) distribution map here. BONAP map color key here.

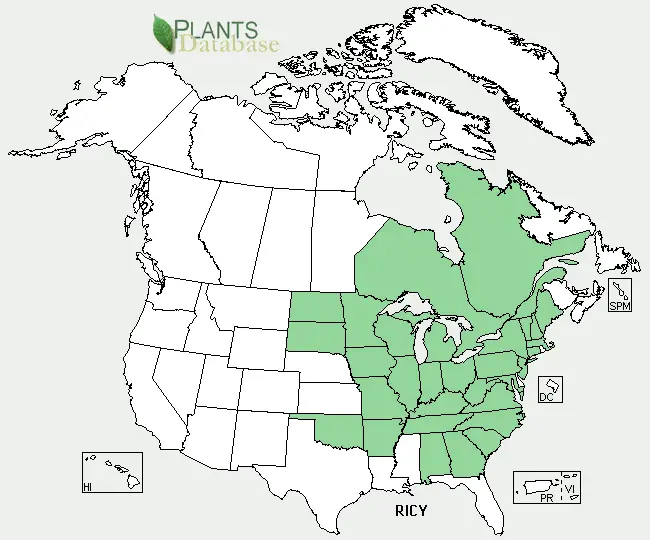

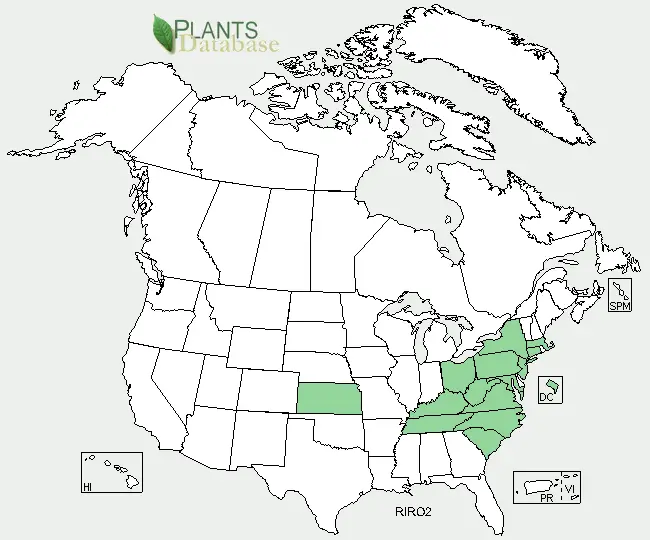

Missouri Gooseberry or Missouri Currant (Ribes missouriense) range. Distribution map courtesy of U. S. Department of Agriculture (USDA Natural Resources Service) and used in accordance with their policies.

Missouri Gooseberry or Missouri Currant (Ribes missouriense) drawing. (USDA-NRCS PLANTS Database / Britton, N.L., and A. Brown. 1913. An illustrated flora of the northern United States, Canada and the British Possessions. 3 vols. Charles Scribner's Sons, New York. Vol. 2: 240.)

Missouri Gooseberry or Missouri Currant (Ribes missouriense) with immature fruit. (By: Eric in SF CC BY-SA 3.0)

Appalachian Gooseberry

Appalachian Gooseberry (Ribes rotundifolium). This one does not occur where I live or have lived, but I have included it for those that live in, or travel to higher elevations in the Appalachian mountains. I have never tasted this one, so I cannot comment on that aspect, but I have read it is very good.

This one reportedly likes neutral to alkaline soils, so it would be interesting to try to grow in areas that are not normally known for Gooseberries as they normally like slightly acidic soils. All reports say the fruit is very good tasting, so it might be worth the effort to see if it would grow outside its normal range.

Description:

- USDA Plant Hardiness Zone: down to zone 6, possibly zone 5 (More information on hardiness zones).

- Soil pH: 6.1-8.5

- Plant Size: 1.5 meters (5 feet) high

- Duration: Perennial Shrub

- Leaf Shape: 3-5 lobed, maple leaf like with rounded lobes

- Leaf Phyllotaxis (Arrangement) on branch: Alternate

- Leaf Size: 5-10 cm (2 to 4 inches) long

- Leaf Margin: Large Serrated (saw toothed edge), rounded. Can be so large as to look like small lobes

- Leaf Notes: Very tiny yellowish dots on leaf.

- Flowers: Hanging clusters of small yellow to white with long tubes from center in mid-spring

- Fruit: When ripe has a Red Grape reddish purple color that has a whitish bloom. 6-8 mm diameter, taste is reported to be very good

- Bark: Mature stems have bark that is in shreds, reddish brown color

- Habitat: Neutral to alkaline soils - so should find in limestone bedrock areas, up to high elevations, partial shade is most common habitat.

Web Resources:

- Pictures on the web here (Google images) and here (Bing images).

- Interactive USDA distribution map and plant profile here.

- The Biota of North America Program (BONAP) distribution map here. BONAP map color key here.

Appalachian Gooseberry (Ribes rotundifolium) range. Distribution map courtesy of U. S. Department of Agriculture (USDA Natural Resources Service) and used in accordance with their policies.

Appalachian Gooseberry (Ribes rotundifolium) drawing. (USDA-NRCS PLANTS Database / Britton, N.L., and A. Brown. 1913. An illustrated flora of the northern United States, Canada and the British Possessions. 3 vols. Charles Scribner's Sons, New York. Vol. 2: 241.)

Appalachian Gooseberry (Ribes rotundifolium) leaves and flowers. (By: USDA, ARS, National Genetic Resources Program. Germplasm Resources Information Network - (GRIN). National Germplasm Resources Laboratory, Beltsville, Maryland, mage taken by Danny Dalton)

Appalachian Gooseberry (Ribes rotundifolium) leaves. (By: USDA, ARS, National Genetic Resources Program. Germplasm Resources Information Network - (GRIN). National Germplasm Resources Laboratory, Beltsville, Maryland, Leaves Collected and scanned by Tyler Young)

Search Wild Foods Home Garden & Nature's Restaurant Websites:

Share:

Why does this site have ads?

Originally the content in this site was a book that was sold through Amazon worldwide. However, I wanted the information to available to everyone free of charge, so I made this website. The ads on the site help cover the cost of maintaining the site and keeping it available.

Google + profile