Search Wild Foods Home Garden & Nature's Restaurant Websites:

Dangerous Plants to Avoid Touching

Contents:

- Poison Ivy

- Western Poison Ivy

- Poison Oak

- Poison Sumac

- Giant Hogweed

- Cow Parsnip

- Wild Parsnip

- Spotted Water Hemlock

- Cowbane or Northern Water Hemlock

- Bulb-bearing Water Hemlock

- White Baneberry (Doll's-eyes) & Red Baneberry

- A Special Threat to Pets and Farm Animals

When out looking for plants to transplant or gathering seeds, make sure you are aware of the following plants so you don't make a mistake and touch them. This is a list of Plants that touching can result in health problems. This list does not include plants with thorns or prickles. Any cuts from thorn or prickles should have an antiseptic applied asap. Best to carry a small bottle of iodine or something similar with you on outings, as there have been cases of serious infection from cuts from thorns and prickles. Rose bush thorn cuts have been known cause serious infections in gardeners.

The Toxicodendron Genus:

This is Poison Ivy and its close relatives. All produce an oil called Urushiol that when absorbed by the skin creates chemical changes that causes about 75% of humans to have an allergic reaction. The blistering and itching is a result of the reaction to the Urushiol by the immune system. BY FAR, THE BEST WAY TO DEAL WITH POISON IVY AND ITS RELATIVES IS TO KNOW THEM WELL AND ALWAYS BE ON THE LOOKOUT WHEN GATHERING WILD FOODS TO PREVENT CONTACT.

Though humans can be badly affected by Poison Ivy, Western Poison Ivy, Poison Oak and Poison Sumac, other animals generally are not. So, if your dog was out where there could have been some, it could be on their fur and there might be no symptoms. If you or your children pat them, or touch them, it could get it all over - rubbing eyes after patting a dog for instance. The best thing to do is shampoo the pet with a soap that cuts oil - vets often recommend liquid dish washing soap - and rinse them well and repeat a second time. I would also advise calling your vet as I've read some dogs can react to Urushiol like humans.

If going into an area where there may be the chance of contacting Poison Ivy, Western Poison Ivy, Poison Oak and Poison Sumac, you may want to consider carrying a little liquid dish soap with you and a bottle of water if you aren't around water. If you think you may have touched Poison Ivy, Oak or Sumac, put soap and water on the area, and wash and rinse. Urushiol is oil based, and liquid dish soap is designed to cut oil. The longer you leave it on, the more it soaks into your skin. Unfortunately, most of the time you don't find out until later when it has soaked in and started causing the itching and blistering. Here is a wikiHow entry on dealing with it after the fact.

Possible Help if there has been contact:

Jewelweed. Although not proven, there is some evidence that both Orange Jewelweed (Impatiens capensis) and Yellow Jewelweed (Impatiens pallida) may reduce the reaction associated with bee stings, Stinging Nettle stings, and Poison Ivy, Western Poison Ivy, Poison Oak and Poison Sumac contact. You have to find it quickly after the sting or contact, mash up the Jewelweed, stems and leaves, and apply the mash to the contact area. Jewelweed likes to grown in damp to wet areas in ditches, along rivers and streams and edges of marshes.

- Pictures of the Orange Jewelweed (Impatiens capensis) on the web here (Google images) and here (Bing images).

- USDA distribution map and plant profile of the Orange Jewelweed (Impatiens capensis) here.

- Pictures of the Yellow Jewelweed (Impatiens pallida) on the web here (Google images) and here (Bing images).

- USDA distribution map and plant profile of the Yellow Jewelweed (Impatiens pallida) here.

If you can't find Jewelweed, or are in a dry area and have contact, you may want to try crushing up Plantain leaves and putting them on the affected areas. It has been used for a long time to reduce itching and help wounds on the skin of any kind. There is a description of the Broadleaf Plantain in the Leaves and Greens section here. For topical use, it doesn't have to be the Broadleaf Plantain, but any of the Plantain (Plantago) genus.

- Pictures of Plantain on the web here (Google images) and here (Bing images).

- Interactive USDA distribution map and plant profile here.

- The Biota of North America Program (BONAP) distribution map here. BONAP map color key here.

Poison Ivy

Poison Ivy (Toxicodendron radicans) - know this plant well enough so that you recognize it when you see it in all its many incarnations. It really does have many incarnations, and different versions of it can be side by side. Many would put the Western Poison Ivy (entry below) in with this one saying it is just yet another version of the plant, I put it separate only because of one that I saw that really was the size of a small tree. It can be a trailing vine that stays low to the ground with what looks like short woody individual plants coming off it. It can be a small shrub up to just over a meter (3 feet) high. It can also be a very adept climbing vine that goes way up trees then hangs off with many branches. If you live in an area that has the Manitoba Maple, also called the Box Elder Acer negundo, the baby Manitoba Maples with the compound leaves with three leaflets can very much look like the low version of Poison Ivy. There are times when I have to really look to be sure which is which. If you are not 100% sure it is a Manitoba Maple, don't touch it.

Most people associate this plant with forests, and for good reason. However, it likes good amounts of light, and is most likely at the edges of woods, and often those are at areas where there is water such as rivers. But since birds spread the seeds, and birds come into the city, and cities often have lots of open tree areas, this plant is more common in city park edges and waste areas than most assume, so don't automatically stop looking for it if you are city foraging.

Always be conscious that the roots are just as bad, if not worse, than the leaves for the (Urushiol), which is the oil that causes the reaction and resulting dermatitis. This is very important to know if you are digging for root or tuber foods where Poison Ivy is growing.

It is estimated that about one in four people are not affected by Poison Ivy. It is not poisonous in itself, it's just that the Urushiol causes an allergic reaction. If you don't have the allergic reaction, you won't have any problem. In a way, it's like peanut allergy. If you are not allergic to peanuts, you can eat them, but if you are allergic to peanuts, they can be very dangerous to you. The only difference is, that a very high proportion of humans are allergic to Poison Ivy, while a small percentage are allergic to peanuts. Be very aware that if you know you don't react to it, that you could the next time you touch it. Seems it is one of those allergic reactions that can change. Also, if you happen to know you are allergic to either cashews or mangos, be especially careful with Poison Ivy or any of the others - Poison Oak and Poison Sumac, as they are from the same family of plants.

I have read on the web recommendations to eat very small amounts of the leaves in spring when they are red to provide immunity to the reaction. I personally think this is a very dangerous experiment with your life, and irresponsible of those that recommend it. If you follow this, and do have a reaction - it will be in your mouth, throat, stomach, and possibly throughout your body, and on top of being very painful, could be life threatening. I very, very strongly advise NOT to try this even with very small amounts.

I just want to add a final thought. Don't hate the plant or be afraid of it - it is not some form of evil disguised as a plant. Other animals are not allergic to it - it's just us humans (and maybe some dogs), and even then, only three out of four people. It provides food for many birds in the winter when there is little else but Poison Ivy berries, and some animals forage the leaves for food. Goats munch away at it without issue. It has also been used medicinally in preparations for arthritis, liver disorders, and amazingly, for skin conditions, and is used in homoeopathy as well. Respect it, and best to stay away from it. Think of it as high voltage electricity - you don't hate electricity, but it is wise not to grab live wires.

- Plant Size: Can take many forms. One, can be a trailing vine with upright woody stems that are usually less than 30 cm (1 foot) high, can be a climbing vine that can go a few meters up along tree trunks and have branches that come off and hang over the ground like the tree branches, can take the form of a small shrub, that is usually no more than a meter (3 feet) high - a highly variable plant

- Duration: Perennial

- Leaf Shape: Trifoliate compound leaf, leaflet shape is remarkably variable

- Leaf Phyllotaxis (Arrangement) on branch: Alternate

- Leaf Size: Generally the leaflets are 3–12 cm (1 1/5 to 4 3/4 inches) long, though they can get more than double that in ideal conditions

- Leaf Margin: Can be large, course Serrated (saw toothed edge) or Entire (smooth edged) or a mix. Often if mixed, the large sawtooth edges are nearer the tip of the leaf, and the smooth margin is near the base. Sometimes there are two lobes on the center leaf, with one lobe on side leaves. This is a highly variable plant.

- Leaf Notes: Leaves can have a red color in spring or be light green. Dark green in summer. Red, orange or yellow in fall. Generally, the upper sides of the leaves are shiny with sparse, short white hairs. Again, this is a highly variable plant in all respects.

- Flowers: Clusters of small flowers above leaves. Light yellow to white with a green tint.

- Fruit: Clusters of small dull white to light grey berries (smaller than average peas). Very common to see them in winter as they stay attached long after the leaves have fallen.

- Bark: Medium grey with light grey to whitish blotches. Most often seen as vine on the side of a tree covered with auburn red hairs, often grey hairs too.

- Habitat: All over Eastern North America. Though this plant does well in most moisture conditions except extreme dryness, it is most often found by creeks and rivers and ponds. This may be due to its need for light - it does not like dark shade - and edges of water areas often break the dark shade of woods. For this reason, it is very often found at the edges of woods not near water as well. It can adapt to acidic to alkaline soils. It is tolerant of areas that are flooded in the spring - such as river side flood plains. Likes open (well lit) treed areas in cities - birds eat the berries and drop the seeds unharmed when they are on branches.

- Pictures on the web here (Google images) and here (Bing images).

- Pictures of the berries on the web here (Google images) and here (Bing images).

- Interactive USDA distribution map and plant profile here.

- The Biota of North America Program (BONAP) distribution map here. BONAP map color key here.

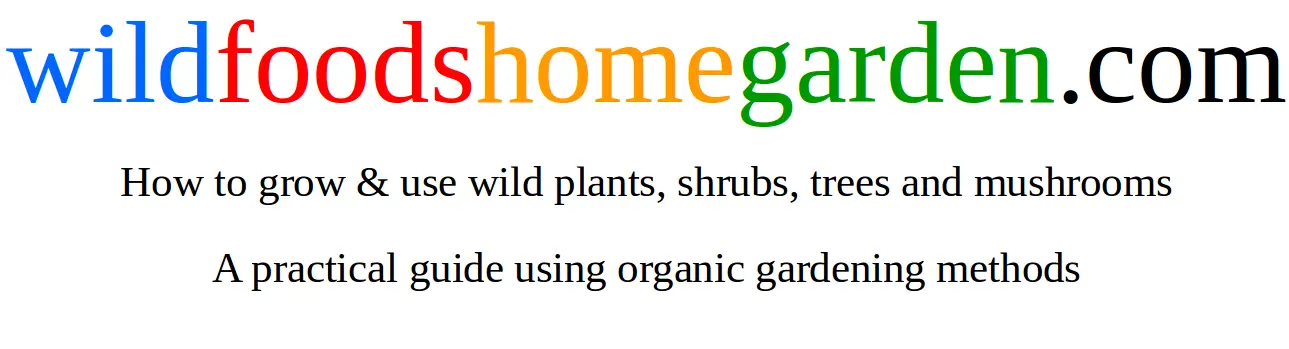

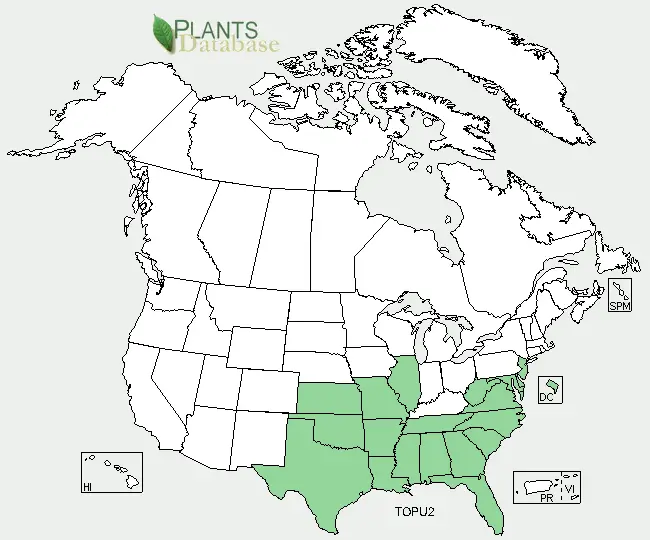

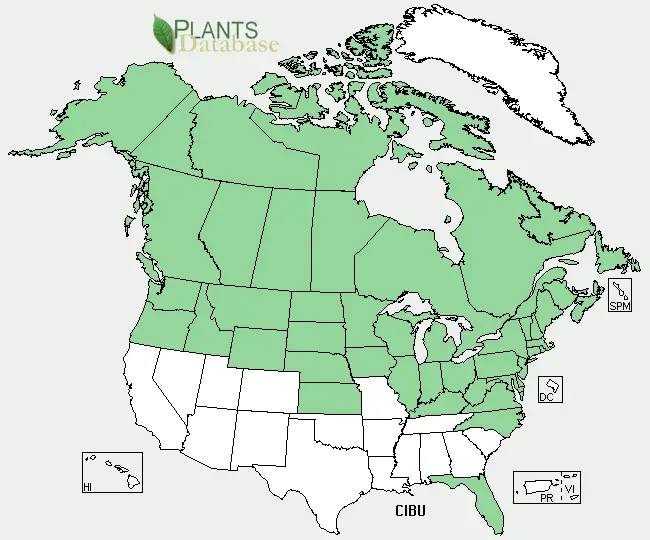

Poison Ivy (Toxicodendron radicans) range. Distribution map courtesy of U. S. Department of Agriculture (USDA Natural Resources Service) and used in accordance with their policies.

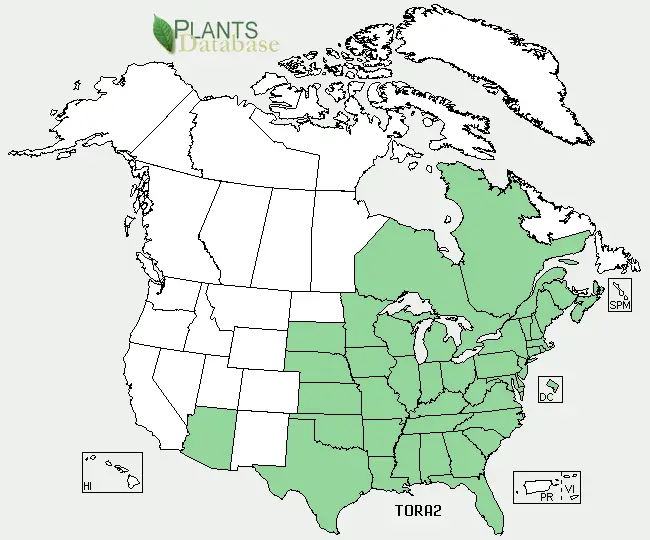

Poison Ivy (Toxicodendron radicans) drawing. (USDA-NRCS PLANTS Database / Britton, N.L., and A. Brown. 1913. An illustrated flora of the northern United States, Canada and the British Possessions. 3 vols. Charles Scribner's Sons, New York. Vol. 2: 484.)

Poison Ivy (Toxicodendron radicans) leaves in spring. (By: D. Gordon E. Robertson CC BY-SA 3.0)

Poison Ivy (Toxicodendron radicans) leaves in spring up close. (Robert H. Mohlenbrock, hosted by the USDA-NRCS PLANTS Database / USDA SCS. 1991. Southern wetland flora: Field office guide to plant species. South National Technical Center, Fort Worth.)

Poison Ivy (Toxicodendron radicans) leaves in Summer. (By: Hardyplants)

Poison Ivy (Toxicodendron radicans) flowers under leaves. (By: Randy Nonenmacher CC BY-SA 3.0)

Poison Ivy berries at the green stage in late summer. This is from a Poison Ivy about 6 meters (20 feet tall) growing on a Cottonwood tree in Springbank Park, London, Ontario. I've been watching this specimen for about 20 years. Hundreds of people go by this every day and have no idea it is there. This picture is taken of the branch of it that hangs about 3 meters (10 feet) off the ground - right over a very busy bike and walking path.

Poison Ivy (Toxicodendron radicans) berries in fall. (By: H. Zell GNU Free Documentation License, Version 1.2)

This is a close up detail of the Poison Ivy vine growing up the side of the Cottonwood tree in Springbank Park. Note the reddish hairs growing off the vine. If you see this on a trunk of a tree, do not touch. Most people think of the leaves of the Poison Ivy as the part that gives the rash, but any part of the plant is to be avoided - including the roots. English or Irish Ivy vines growing up the side of a tree can have a similar look. Make sure you know the difference.

This is what very large Poison Ivy vines looks like in Winter. This group is growing up the side of a White Cedar. This is another one in Springbank Park, London, Ontario just a couple of meters from a very busy paved path and a meter from an unpaved path. At least 30 years old.

This is the Poison Ivy on the Cottonwood (Populus deltoides) in Springbank Park. This is a picture of the plant at over 6 meters (20 feet) off the ground. To the unfamiliar, this looks like part of the tree.

Western Poison Ivy

Western Poison Ivy (Toxicodendron rydbergii). Although called the Western Poison Ivy, this is all over the east as well - right to the Atlantic. The only place it is not native is the very South-East USA. A better name for it would by the Bush or Shrub Poison Ivy, as this is very similar to the vine type Poison Ivy, except while Poison Ivy is small ground cover to large vine, this is a bush or shrub that can grow as large as 3 meters (10 feet) tall or more. I saw one once on the side of the Thames River in London, Ontario that was about 10-12 feet tall with a trunk that was about 4-5 inches diameter. The trunk was a tightly interwoven mass of three or four trunks that had grown tightly together over time. I saw the trunk on a walk along the river path, and had a "what the heck is that?" moment, went over to it, looked up and was shocked at what I saw - a Poison Ivy tree. Up to that point I had no idea there was such a thing. (No pictures, this was a decade before the digital camera came into being, and is gone now, as it stood on the west side of the Thames river exactly where the Oxford Street extension bridge was put in by the Hunt Club. In a way, too bad - it was an amazing specimen, I've often wondered how old that tree was. The whole area is basically gone to subdivisions - it was a remarkable old growth Carolinian forest that could take your breath away). Though this Poison Ivy shrub is very common where I live in Southwestern Ontario, most people are not aware of it, and think of the vine Poison Ivy when they hear the name "Poison Ivy". Because of that, people are not on the lookout for it, and are more likely to accidentally come in contact with it. This is especially true in the fall when the bright red to orange foliage is very beautiful.

- Plant Size: Small shrub to small tree size, reaching over 3 meters (10 feet) tall

- Duration: Perennial

- Leaf Shape: Trifoliate compound leaf, with variable leaflet shape, but often a triangular to Ovate

- Leaf Phyllotaxis (Arrangement) on branch: Alternate

- Leaf Size: Generally the leaflets are 3–12 cm (1 1/5 to 4 3/4 inches) long, though they can get more than double that in ideal conditions

- Leaf Margin: Like the Poison Ivy listed above, can be large, course Serrated (saw toothed edge) or Entire (smooth edged) or a mix, but this one is more likely to have the serrated edge, at least on the upper part of the leaf.

- Leaf Notes: Leaflet shape is highly variable, even on the same plant

- Flowers: Same as Poison Ivy listed above, clusters of yellowish to light white-green flowers on stem

- Fruit: Very similar to the Poison Ivy listed above, but the berries often have a yellow tint to them.

- Bark: Medium Grey, with lighter grey to white blotching, can have red hairs

- Habitat: Fields, openings in woods, almost anywhere it can get enough light

- Pictures on the web here (Google images) and here (Bing images).

- Interactive USDA distribution map and plant profile here.

- The Biota of North America Program (BONAP) distribution map here. BONAP map color key here.

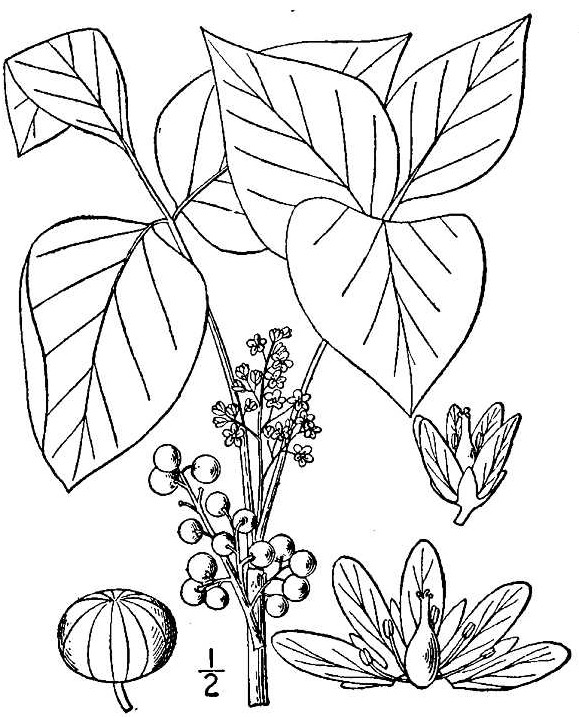

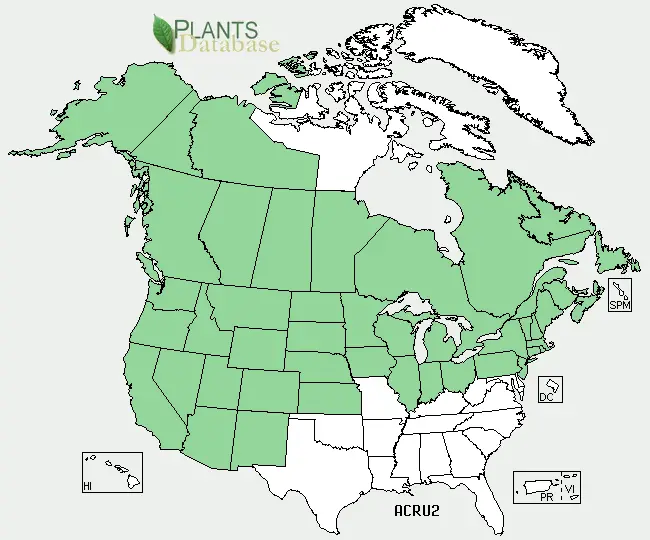

Western Poison Ivy (Toxicodendron rydbergii) range. Distribution map courtesy of U. S. Department of Agriculture (USDA Natural Resources Service) and used in accordance with their policies.

Western Poison Ivy (Toxicodendron rydbergii). (By: Dave Powell, USDA Forest Service CC BY-SA 3.0)

Western Poison Ivy (Toxicodendron rydbergii). (By: Dave Powell, USDA Forest Service CC BY-SA 3.0)

.jpg)

Western Poison Ivy (Toxicodendron rydbergii) in spring. (By: Joshua Mayer (wackybadger) Attribution 2.0 Generic)

.jpg)

Western Poison Ivy (Toxicodendron rydbergii) flower spike with unopened buds in mid-June. (By: Joshua Mayer (wackybadger) Attribution 2.0 Generic)

Western Poison Ivy (Toxicodendron rydbergii) berries in the fall. (By: Whitney Cranshaw, Colorado State University CC BY-SA 3.0)

Poison Oak

Poison Oak (Toxicodendron pubescens) on the east coast (known also as "Atlantic Poison Oak"), and (Toxicodendron diversilobum) on the west coast - Very close relative of the Poison Ivy, Western Poison Ivy, in fact some taxonomists say they really are different forms of the same plant. The plant can be bush sized or larger, and the leaves look like the White and Bur Oak. Since Oak trees that small don't produce acorns, don't touch any small tree or bush that looks like an Oak - unless you are very sure it is an Oak. It has a small berry that is either a yellowish color or greenish later in the year.

- Plant Size: Generally up to 1 meter (3 feet) high, although has been known to reach 3 meters (10 feet)

- Duration: Perennial

- Leaf Shape: Trifoliate compound leaf with leaflets that have big, rounded lobes giving them a White Oak or Burr Oak leaf shape.

- Leaf Phyllotaxis (Arrangement) on branch: Alternate

- Leaf Size: Compound leaves are generally about 15 cm (6 inches) long

- Leaf Margin: Large, rounded lobes

- Leaf Notes: Leaves are very shiny on the upper side, with a velvet like underside. Leaves have 3-7 rounded lobes

- Flowers: clusters of green flowers with small amber centers

- Fruit: Dark to light tan color, covered in fine hairs, green when unripe

- Bark: Dull reddish brown

- Habitat: Almost any conditions in the areas it occurs. Very common in lightly shaded woods, and edges of woods.

- Pictures on the web here (Google images) and here (Bing images).

- Pictures of the berries on the web here (Google images) and here (Bing images).

- Interactive USDA distribution map and plant profile here.

- The Biota of North America Program (BONAP) distribution map here. BONAP map color key here.

Poison Oak (Toxicodendron pubescens) range. Distribution map courtesy of U. S. Department of Agriculture (USDA Natural Resources Service) and used in accordance with their policies.

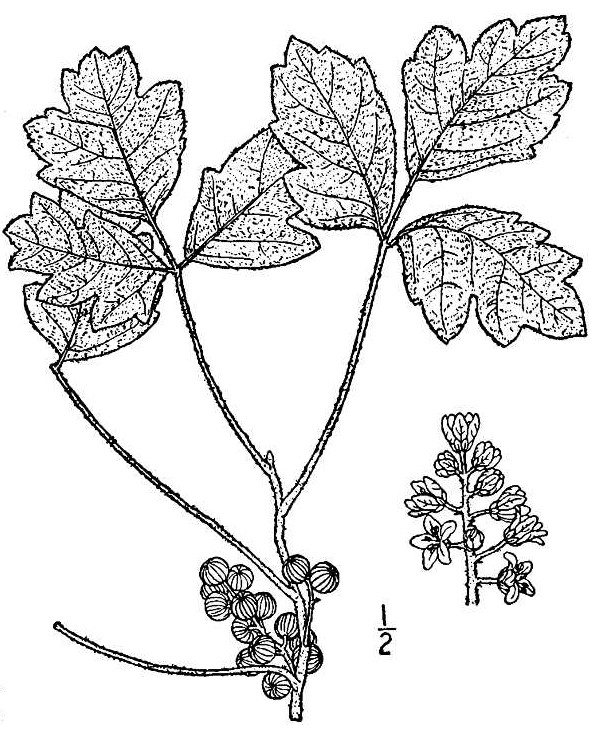

Poison Oak (Toxicodendron pubescens) drawing. (USDA-NRCS PLANTS Database / Britton, N.L., and A. Brown. 1913. An illustrated flora of the northern United States, Canada and the British Possessions. 3 vols. Charles Scribner's Sons, New York. Vol. 2: 484.)

Poison Oak (Toxicodendron pubescens) leaves. (Robert H. Mohlenbrock @ USDA-NRCS PLANTS Database / USDA SCS. 1991. Southern wetland flora: Field office guide to plant species. South National Technical Center, Fort Worth, TX.)

Poison Sumac

Poison Sumac (Toxicodendron vernix) - closely related to both the Poison Ivy, Western Poison Ivy and Poison Oak. This is probably the most dangerous plant in North America to touch. It has the same poison (Urushiol) in it as the Poison Ivy, Western Poison Ivy and Poison Oak, but in much higher concentrations. You must know this plant if you are around damp lands or areas where there is shallow standing water. It does not look at all like a Poison Ivy, and very few people know it. Also, it has nice looking grey to off-white or green when unripe berries that look very, very similar to the Red Osier Dogwood Cornus sericea berries and the White Baneberry or Doll's-eyes berries, though they are duller in color. It is a very beautiful looking plant with striking light yellow green compound leaves with pinkish-red stems and the veins on the underside of the leaf are also a pinkish-red. Each leaflet looks somewhat similar to a Milkweed leaf. Because it is such a beautiful plant, if you don't know what it is, and see it, you may be tempted to touch it while admiring it. The leaves are so large that you might mistake each leaflet on the leaf for leaves themselves, so when reading the description below, be aware of the difference.

- Plant Size: Can grow to a small tree of up to 9 meters(30 feet) tall, but more commonly found much shorter.

- Duration: Perennial

- Leaf Shape: Odd Pinnate (each leaf has 7-13 leaflets that are in opposite pairs with one leaf at the end). Each leaflet is Ovate to Elliptic

- Leaf Phyllotaxis (Arrangement) on branch: Leaves are Alternate, but each leaflet is in Opposite pairs on the leaf stem with a single leaf at the end of the leaf.

- Leaf Size: Each leaflet is 5-10 cm (2 to 4 inches) long

- Leaf Margin: Entire (smooth edged), but very often with a wavy or wandering edge. Distinct creamy-yellow thin border at margin

- Leaf Notes: Leaves have a glossy appearance, yellow-green color, almost translucent quality, with a creamy white thin border around the edge that looks drawn on. The central vein is pinkish-red on the underside of the leaf for the bottom half, but turns a creamy yellow-green by the leaf tip. The pink-red leaf stems get fat at their base where they meet the branch. Sometimes there are very fine hairs on the underside of the leaf.

- Flowers: Showy big clusters of creamy-white flowers on long stems that are 7.5-20 cm (3 to 8 inches) long.

- Fruit: Small, grey to off-white when ripe, green when unripe berries on panicles (clusters) with long drooping stems that are 7.5-20 cm (3 to 8 inches) long.

- Bark: Medium grey with light grey blotches on mature trunks, very often with darker grey spots or lenticels (checking)

- Habitat: Wet areas, areas of very shallow standing water in grassy areas.

- Pictures of Poison Sumac on the web here (Google images) and here (Bing images). As it is the web, some pictures are mislabelled. If you see fuzzy red berries, this is not Poison Sumac, it is Staghorn Sumac Which is not a problem to touch.

- Interactive USDA distribution map and plant profile here.

- The Biota of North America Program (BONAP) distribution map here. BONAP map color key here.

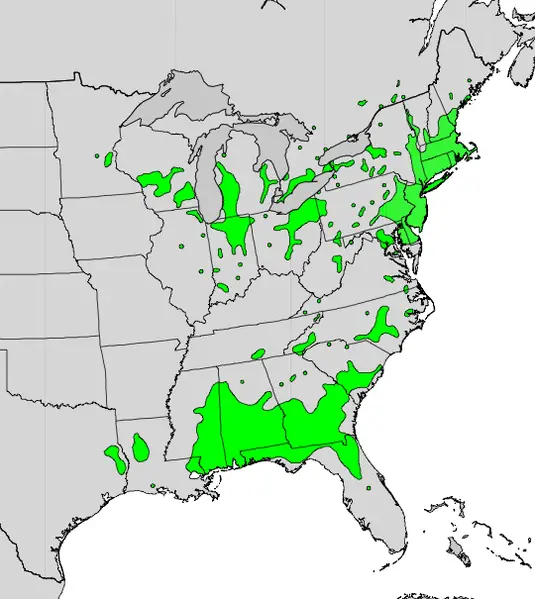

Poison Sumac (Toxicodendron vernix) range. Distribution map courtesy of the USGS Geosciences and Environmental Change Science Center, originally from "Atlas of United States Trees" by Elbert L. Little, Jr. .

Poison Sumac (Toxicodendron vernix) drawing. (USDA-NRCS PLANTS Database / Britton, N.L., and A. Brown. 1913. An illustrated flora of the northern United States, Canada and the British Possessions. 3 vols. Charles Scribner's Sons, New York. Vol. 2: 483)

Poison Sumac (Toxicodendron vernix). Very typical of how it looks. (Norman Melvin, hosted by the USDA-NRCS PLANTS Database)

Poison Sumac (Toxicodendron vernix) in the fall. What you see here are leaflets that are part of a leaf - not all of which is visible in this photo. (Robert H. Mohlenbrock, hosted by the USDA-NRCS PLANTS Database / USDA SCS. 1991. Southern wetland flora: Field office guide to plant species. South National Technical Center, Fort Worth)

Poison Sumac (Toxicodendron vernix) drawing. This shows how each leaf attaches to the main stem. NOTE: in this drawing it is showing just one leaf with seven leaflets. The pinkish part the leaflets are attached to is the leaf stem. There are NOT seven leaves showing here. You must understand this difference. See the Notes on Identification page to read about telling the difference. (Adolphus Ypey, Vervolg ob de Avbeeldingen der artseny-gewassen met derzelver Nederduitsche en Latynsche beschryvingen, Eersde Deel, 1813)

Poison Sumac (Toxicodendron vernix) in June. (By: Freekee Creative Commons CC0 1.0 Universal Public Domain Dedication)

The Apiaceae (or Umbelliferae) family:

Commonly known as the Parsley or Carrot family, this is a very large family of well known and not well known plants, many of which are common foods. Better known examples include: Angelica, Anise, Arracacha, Asafoetida, Caraway, Carrots, Celery, Chervil, Cicely, Cilantro, Coriander, Cumin, Dill, Fennel, Hemlock, Lovage, Queen Anne's lace, Parsley, Parsnips and Wild Parsnips. This family also has some of the most deadly members of the plant kingdom - the Hemlocks. Many in the Parsley family contain a phototoxin (furocoumarins) that reacts with ultraviolet light to produce burns and blisters on the skin that are often mistaken for Poison Ivy. Celery for instance is well known in Europe to produce very serious allergic reactions, garden Parsnip at certain times of its life cycle has enough to create burns where a person has had contact with the foliage, Queen Anne's lace is known for this as well. I've listed some of the worst offenders in this group below. Also, I've included the related Hemlocks, that though they are not known for the burns and blisters, reportedly can create sickness and even death if there is contact with the sap.

Giant Hogweed

Giant Hogweed (Heracleum mantegazzianum). Can cause serious burning and blistering on skin by touching it, and blindness if you rub your eyes after touching it. Known also as Cartwheel-flower, Giant Cow Parsnip, Giant Cow Parsley. Basically, the plant looks like a super-monster version of the Queen Ann's Lace. Monstrous leaves, gigantic flowers. No surprise that three out of the four common names have the word "Giant" in front. The large green stems have reddish-purple blotches all over them, and there are course hairs in those blotches. It shows up in damp areas in openings where there are grassy areas, ditches, waste land, power line cuts, by marsh land, etc. Very important not to touch it, but if you do - do not rub your eyes as blindness can be the result.

- Plant Size: Up to 5 meters (16 feet) tall

- Duration: Perennial living 5-7 years generally

- Leaf Shape: Huge compound leaves with large lobed to deeply lobes leaflets that can be of varying shapes. Can be Christmas tree shaped, Maple leaf like, or with three large lobes giving a (sort-of) clover leaf shape

- Leaf Phyllotaxis (Arrangement) on branch: Alternate

- Leaf Size: Generally the compound leaf is 1-1.5 meters (3 to 5 feet) diameter

- Leaf Margin: Large Serrated (saw toothed edge)

- Leaf Notes: Highly variable in shape depending on what stage of life cycle the plant is in

- Flowers: Very large, round, white. Upper flower cluster can be up to 60 cm (2 feet) or more in diameter. Lower flower stems come from leaf axils on stem.

- Fruit: Large seeds, brown and tan when ripe, with a flat wing like structure all around the center seed.

- Bark: Dark reddish-purple blotched green stem that can reach 10 cm (4 inches) diameter at the base

- Habitat: Damp, sunny areas - ditches, wet power line cuts, damp areas by streams, rivers, creeks. Since it used to be an ornamental, often found near settlements, having escaped from gardens.

- Pictures on the web here (Google images) and here (Bing images).

- Interactive USDA distribution map and plant profile here.

- The Biota of North America Program (BONAP) distribution map here. BONAP map color key here.

Giant Hogweed (Heracleum mantegazzianum) range. Distribution map courtesy of U. S. Department of Agriculture (USDA Natural Resources Service) and used in accordance with their policies.

_JPG1a.jpg)

Giant Hogweed (Heracleum mantegazzianum). What an amazing looking plant. (Jean-Pol GRANDMONT CC BY-SA 3.0)

Giant Hogweed (Heracleum mantegazzianum) flower umbel. (By: huhu Uet CC BY-SA 3.0 Not permitted to upload this image to Facebook due to incompatibly with Facebook's licensing terms.)

Giant Hogweed (Heracleum mantegazzianum). Young plant in April. (By: Spantax GNU Free Documentation License, Version 1.2)

Cow Parsnip

Cow Parsnip (Heracleum maximum) - Can cause blistering of the skin, and make the skin very sensitive to light causing sunburns very rapidly. This is listed as an edible by some with proper processing, but I strongly suggest just avoiding it. Also, can easily be confused with the Giant Hogweed to the inexperienced.

- Plant Size: Can grow to over 2 meters (7 feet) high

- Duration: Short life Perennial

- Leaf Shape: Compound, very large, each leaflet is very large and slightly Maple leaf like (especially the end leaflet), with very deep lobes

- Leaf Phyllotaxis (Arrangement) on branch: Compound leaves are Alternate on stem, but leaflets on the compound leaf are Opposite

- Leaf Size: Each leaflet up to 40 cm (16 inches) wide

- Leaf Margin: Serrated (saw toothed edge)

- Leaf Notes: The stems on the compound leaves are dark reddish and hairy

- Flowers: White, flat to domed compound flowers up to 25 cm (10 inches) diameter. They look very much like Queen Ann's Lace flowers

- Fruit: Tan with brown lines or stripes and wing like outer edge. 5-12 mm long

- Bark: Green with hairs and lines and channels that run along the stem

- Habitat: Widespread in any habitat that has a lot of sunlight. Fields, waste areas, power line cuts, edges of woods, along rivers, openings in woods, disturbed land, high altitude.

- Pictures on the web here (Google images) and here (Bing images).

- Interactive USDA distribution map and plant profile here.

- The Biota of North America Program (BONAP) distribution map here. BONAP map color key here.

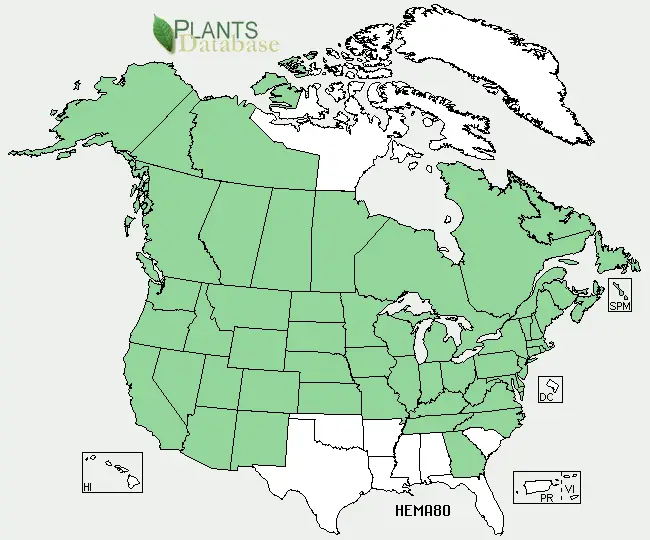

Cow Parsnip (Heracleum maximum) range. Distribution map courtesy of U. S. Department of Agriculture (USDA Natural Resources Service) and used in accordance with their policies.

Cow Parsnip (Heracleum maximum) (By: Danielle Langlois, at Cap Bon-Ami in the Forillon National Park of Canada, Québec GNU Free Documentation License, Version 1.2)

Cow Parsnip (Heracleum maximum). Note how the flowers are opening from the huge buds. (By: Dcrjsr CC BY-SA 3.0)

Cow Parsnip (Heracleum maximum) flower. (By: Danielle Langlois, at Cap Bon-Ami in the Forillon National Park of Canada, Québec GNU Free Documentation License, Version 1.2))

Cow Parsnip (Heracleum maximum) leaf. (Robert H. Mohlenbrock, hosted by the USDA-NRCS PLANTS Database / USDA SCS. 1989. Midwest wetland flora: Field office illustrated guide to plant species. Midwest National Technical Center, Lincoln.)

Wild Parsnip

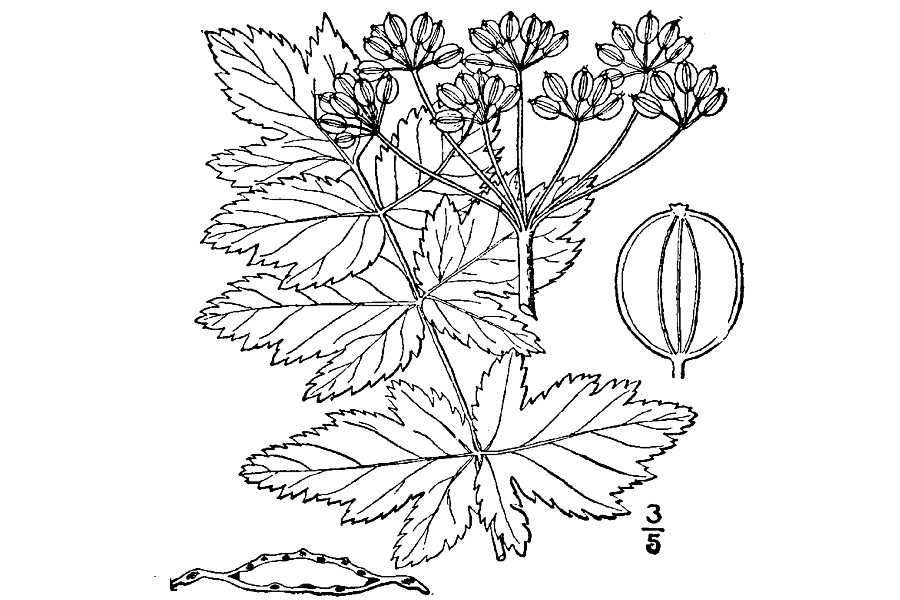

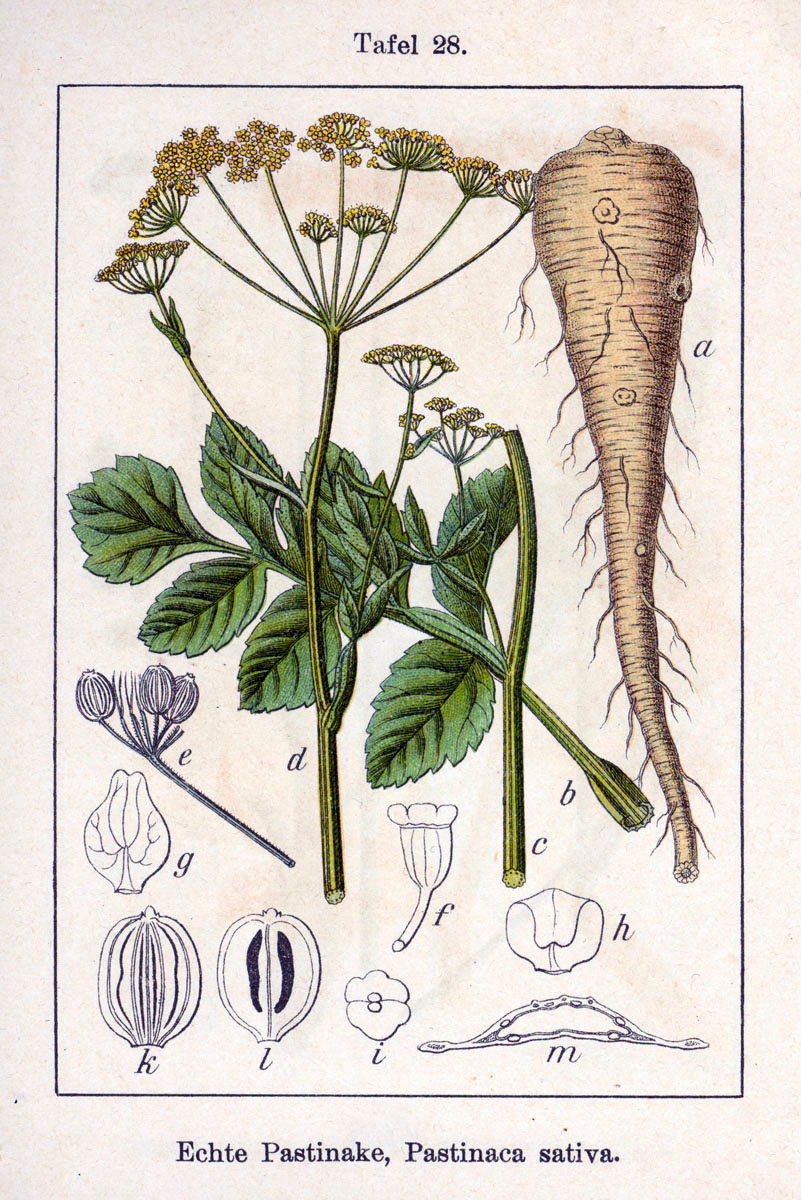

Wild Parsnip (Pastinaca sativa). Known also as the Poison Parsnip. Native to Europe, but naturalized all over North America. This is the same plant as the domestic Parsnip. It is very common all across North America now. The problem with this one is the plant in the second year produces the same chemicals as the Cow Parsnip and can badly burn the skin and leave long term scars.

- Plant Size: Up to about 1.5 meters (60 inches) tall in the first year and 2 meters (80 inches) in the second year with the flower stalks.

- Duration: Biennial, leaves only in the first year, flowering in second year.

- Leaf Shape: Basal leaves: Single or double compound leaf. Odd Pinnate. Leaflets more or less Ovate, terminal leaflet almost round. Leaflets are sometimes 3 lobed.

- Leaf Phyllotaxis (Arrangement) on branch: First year compound leaves are (rosette) of basal leaves (leaves at the base). Leaves on stem are Alternate.

- Leaf Size: Basal compound leaves: 40 cm (16 inches) long. Leaflets: Up to 7.5 cm (3 inches) long by 5 cm (2 inches) wide. Upper compound leaves and their leaflets are much smaller.

- Leaf Margin: Basal compound leaf leaflets are large Serrated (saw toothed edge)

- Leaf Notes: The lower leaflets on the basal leaves have very short stems, while the upper ones have no stems on the leaflets at all.

- Flowers: Umbels of flat top, 7.5-20 cm (3 to 8 inches) wide with tiny yellow flowers. Very similar looking to Queen Ann's Lace flowers, but bigger and yellow.

- Fruit: flattened, winged brown seed with darker lines

- Stem: Hairless, with ridges along stem.

- Habitat: Almost anywhere where there is full sun and not standing water. Disturbed areas, fields, roadsides, meadows, edges of woods.

- Pictures on the web here (Google images) and here (Bing images).

- Interactive USDA distribution map and plant profile here.

- The Biota of North America Program (BONAP) distribution map here. BONAP map color key here.

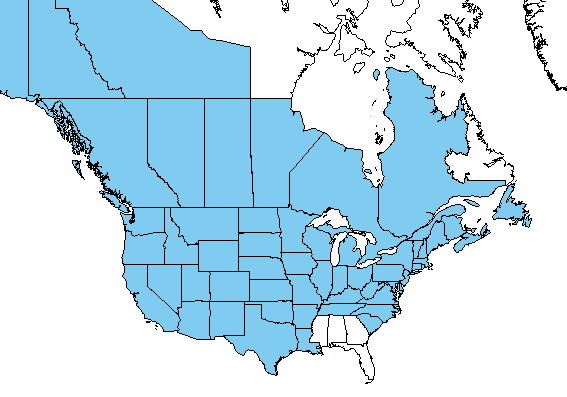

Wild Parsnip (Pastinaca sativa) range. Distribution map courtesy of U. S. Department of Agriculture (USDA Natural Resources Service) and used in accordance with their policies.

Wild Parsnip (Pastinaca sativa) drawing. (USDA-NRCS PLANTS Database / Britton, N.L., and A. Brown. 1913. An illustrated flora of the northern United States, Canada and the British Possessions. 3 vols. Charles Scribner's Sons, New York. Vol. 2: 634.)

Wild Parsnip (Pastinaca sativa). Very typical of what it looks like when you find one in the wild. This is a second year plant as it has flowers. (By: Olivier Pichard CC BY-SA 3.0)

Wild Parsnip (Pastinaca sativa) flower umbel up close. The thing to note here is the mustard yellow color which is quite noticable in the wild. (By: H. Zell GNU Free Documentation License, Version 1.2)

Wild Parsnip (Pastinaca sativa) leaf. (Patrick J. Alexander, hosted by the USDA-NRCS PLANTS Database)

Wild Parsnip (Pastinaca sativa) first year plant. It is easy to identify this plant when in flower in its second year when the root is no good for eating, but hard to identify in the first year when the root is good for eating. (Patrick J. Alexander, hosted by the USDA-NRCS PLANTS Database)

Wild Parsnip (Pastinaca sativa). You can get this kind of root if garden grown in loose, deep loam. (Fig. from book Deutschlands Flora in Abbildungen)

Wild Parsnip (Pastinaca sativa). This is the reality of what you get for a parsnip root when gathered in the wild from my experience. (Flora Batava, Volume 5 (1828), Jan Kops, Christiaan Sepp illustrator.

Water Hemlock

Water Hemlock (Cicuta) - very poisonous plant that can cause a very nasty death by eating parts of it. There are stories where rubbing it on the skin has has led to death. Children using the hollow stems for pea shooters have been made very sick as well. Technically, this group are not poisonous to the touch in the same way as the others listed above can be, but since rubbing it on the skin, and touching the stems to the mouth can be serious, I thought best to include in the section of plants that are dangerous to touch. If you do handle them, wash your hands before eating food, and do not bring them indoors. If you get the sap on your skin where they are cut or crushed, wash off right away - the sap can be absorbed by the skin.

Spotted Water Hemlock

Spotted Water Hemlock (Cicuta maculata). Known also as: Spotted Cowbane, Spotted Parsley.

- Plant Size: Up to 1.5 meters (5 feet) tall

- Duration: Biennial or Perennial with a short life span

- Leaf Shape: Double to occasionally triple compound leaves. 3-7 leaflets per leaf. Leaflets Odd Pinnate to double Odd Pinnate. Each leaflet is Elliptic to Ovate

- Leaf Phyllotaxis (Arrangement) on branch: compound leaves are Alternate on stem.

- Leaf Size: Lower leaves are larger than upper leaves. Lower compound leaves can be up to 46 cm (18 inches) long and 23 cm (9 inches) wide

- Leaf Margin: Large Serrated (saw toothed edge)

- Leaf Notes: Leaflets fold upwards slightly along the central vein. Lateral veins on each leaflet terminate in the recess of the serrations, not at the tip of the serrations - this is not common, and a good identifier.

- Flowers: Compound (stem that branches into stems with flowers), white, round (both the whole compound flower and each small one that makes up the compound flower), flat to domed, on stems, look very much like the closely related Queen Ann's Lace flower.

- Fruit: Small oval to crescent moon shaped light brown with tan strips

- Bark: Stems are pale green to pink to reddish-purple. Often with obvious vein like lines running along stems

- Habitat: Wet areas, areas where the soil is always damp, openings in woods by water, sides of swamps and wetlands.

- Pictures on the web here (Google images) and here (Bing images).

- Interactive USDA distribution map and plant profile here.

- The Biota of North America Program (BONAP) distribution map here. BONAP map color key here.

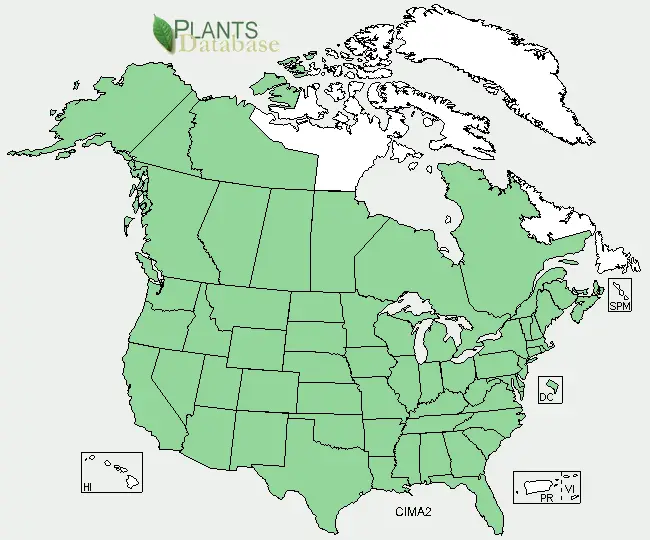

Spotted Water Hemlock (Cicuta maculata) range. Distribution map courtesy of U. S. Department of Agriculture (USDA Natural Resources Service) and used in accordance with their policies.

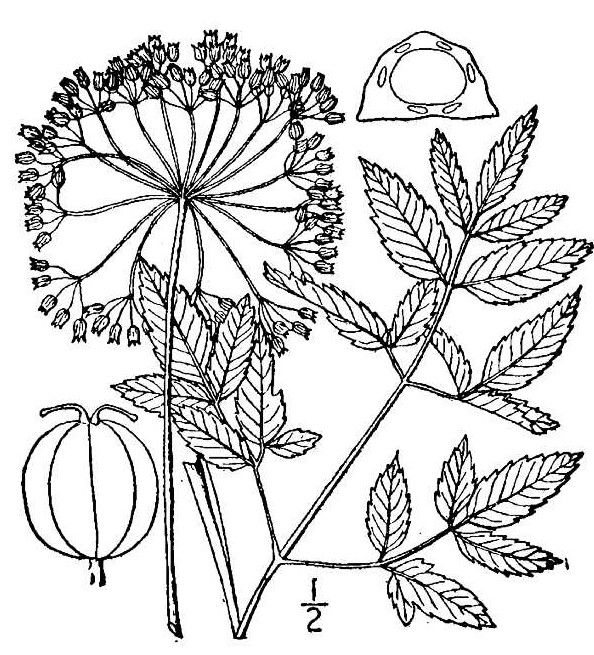

Spotted Water Hemlock (Cicuta maculata) drawing. (USDA-NRCS PLANTS Database / Britton, N.L., and A. Brown. 1913. An illustrated flora of the northern United States, Canada and the British Possessions. 3 vols. Charles Scribner's Sons, New York. Vol. 2: 658.)

Spotted Water Hemlock (Cicuta maculata). Fairly typical of what it looks like when you happen upon one. (By: Choess CC BY-SA 3.0)

Spotted Water Hemlock (Cicuta maculata) flower umbel (By: Choess CC BY-SA 3.0)

Cowbane

Cowbane or Northern Water Hemlock (Cicuta virosa). Sometimes also called the European Water-hemlock, though it is native to northern parts of North America, and also known as Mackenzie's Water Hemlock. As far as I'm aware, this plant does not occur in the United States, but only Canada.

- Plant Size: Up to 2 meters (6 feet) tall

- Duration: Short life Perennial

- Leaf Shape: Compound - tripinnate (Odd Pinnate with three leaves), though very often one of the side leaves hasn't formed leaving only two leaflets.

- Leaf Phyllotaxis (Arrangement) on branch: Alternate

- Leaf Size: Variable

- Leaf Margin: Large Serrated (saw toothed edge)

- Leaf Notes: The sawtooth margins can be so deep that they border on being lobes

- Flowers: Clean white, Queen Ann's Lace like, compound flower, made up of smaller circular to spherical flowers on stems that on the whole make up a larger circular to domed flower - (fractal like). Sometimes the smaller flowers are close enough that you don't notice right away they are separate, sometimes each smaller flower is well spaced.

- Fruit: Small seed, tan with brown strips and wing like structure around the seed, generally oval shaped

- Bark: Stems is smooth, wide at the base, hollow except at the joints - much like bamboo, green with purple stripes

- Habitat: Wet area, very damp soils, full sun, North of USA/Canada border as far as I'm aware.

- Pictures on the web here (Google images) and here (Bing images).

- Interactive USDA distribution map and plant profile here.

- The Biota of North America Program (BONAP) distribution map here. BONAP map color key here.

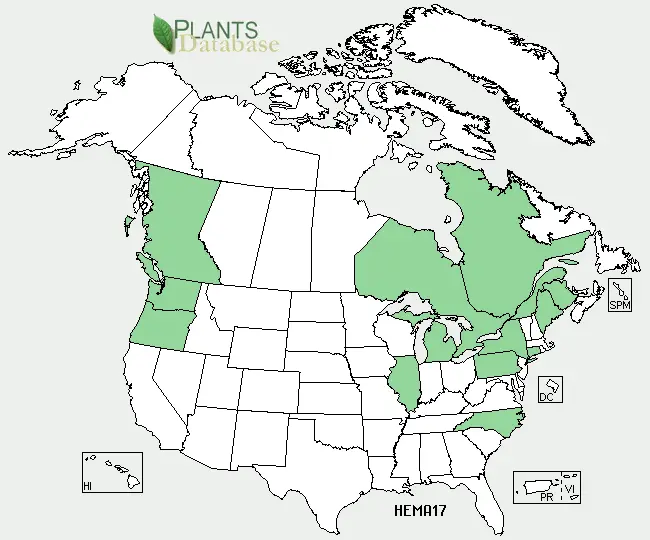

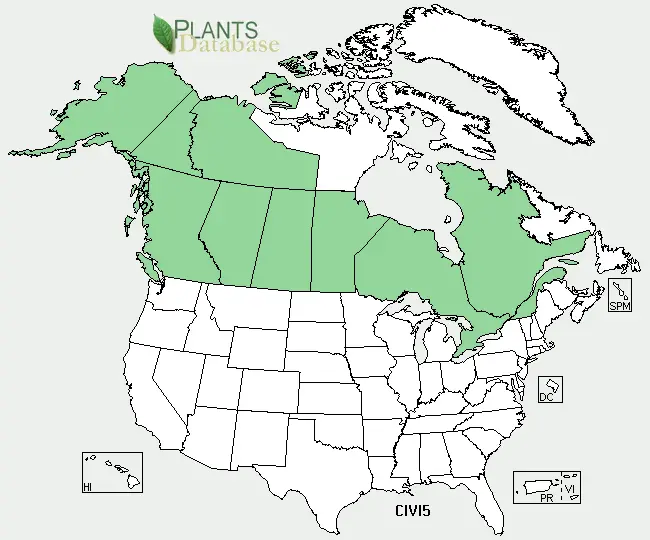

Cowbane or Northern Water Hemlock (Cicuta virosa) range. Distribution map courtesy of U. S. Department of Agriculture (USDA Natural Resources Service) and used in accordance with their policies.

Cowbane or Northern Water Hemlock (Cicuta virosa). Common place for this plant to grow. What is important to note with this picture is the color of the leaves - a very distinctive blueish-green. (By: Anneli Salo CC BY-SA 3.0)

Cowbane or Northern Water Hemlock (Cicuta virosa) flower umbel with the distinctive pom-pom shaped flower clusters. (By: Olivier Pichard CC BY-SA 3.0)

Cowbane or Northern Water Hemlock (Cicuta virosa) leaves. Though not palmate, there is a resemblance to hemp leaves that makes this potentially dangerous to someone who sees this plant when not in flower. To be exact, these are tripinnate compound leaves. (By: Kristian Peters -- Fabelfroh GNU Free Documentation License, Version 1.2)

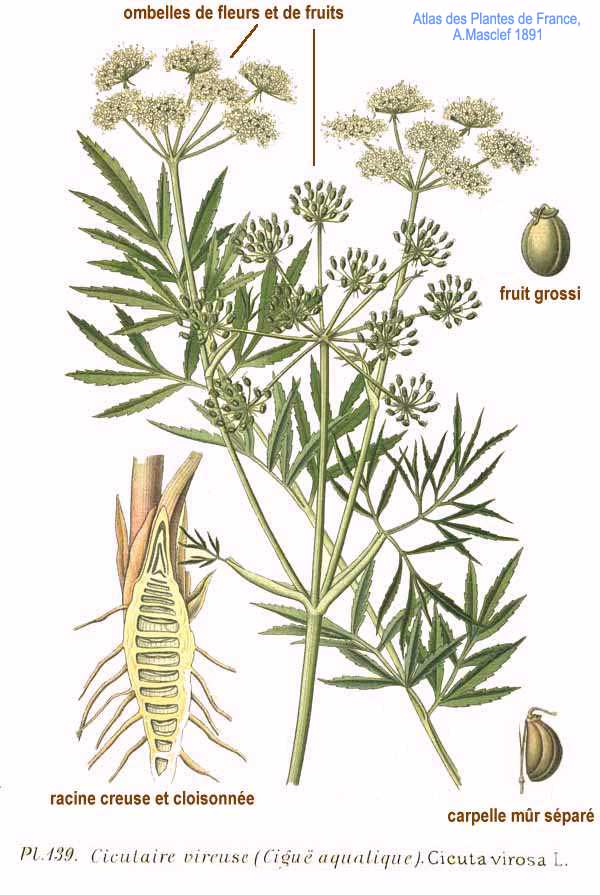

Cowbane or Northern Water Hemlock (Cicuta virosa) illustration. (From: Atlas des plantes de France. 1891 by: Amédée Masclef)

Cowbane or Northern Water Hemlock (Cicuta virosa) illustration (By: Prof. Dr. Otto Wilhelm Thomé Flora von Deutschland, Österreich und der Schweiz 1885, Gera, Germany)

Bulb-bearing Water Hemlock

Bulb-bearing Water Hemlock (Cicuta bulbifera)

- Plant Size: Up to just a bit over 1 meter (3 feet) tall

- Duration: Perennial

- Leaf Shape: Compound, each leaflet is long and very thin. Sometimes lower leaflets are themselves compound.

- Leaf Phyllotaxis (Arrangement) on branch: Alternate

- Leaf Size: Lower leaves up to 30 cm (12 inches) long, 15 cm (6 inches) wide. Upper leaves are smaller than lower leaves. Leaflets up to 7.5 cm (3 inches) long, and 0.8 cm (1/3 inch) wide

- Leaf Margin: Sometimes Entire (smooth edged), sometimes with very large Serrated (saw toothed edge) margins, sometimes both on the same plant. Sometimes there are lobes.

- Leaf Notes: In leaf axils, bulbils grow (tiny bulbs) that give the plant its Latin and Common name. Extremely variable with shape, but overall, long and thin leaflets

- Flowers: Double compound flowers up to 10 cm (4 inches) diameter. Made up of smaller, round, domed compound flowers made up of little white flowers.

- Fruit: Very small, striped, with wing like sides

- Bark: Stems are light green with reddish hue

- Habitat: Wet areas, sides of marshes and rivers, on debris in water.

- Pictures on the web here (Google images) and here (Bing images).

- Interactive USDA distribution map and plant profile here.

- The Biota of North America Program (BONAP) distribution map here. BONAP map color key here.

Bulb-bearing Water Hemlock (Cicuta bulbifera) range. Distribution map courtesy of U. S. Department of Agriculture (USDA Natural Resources Service) and used in accordance with their policies.

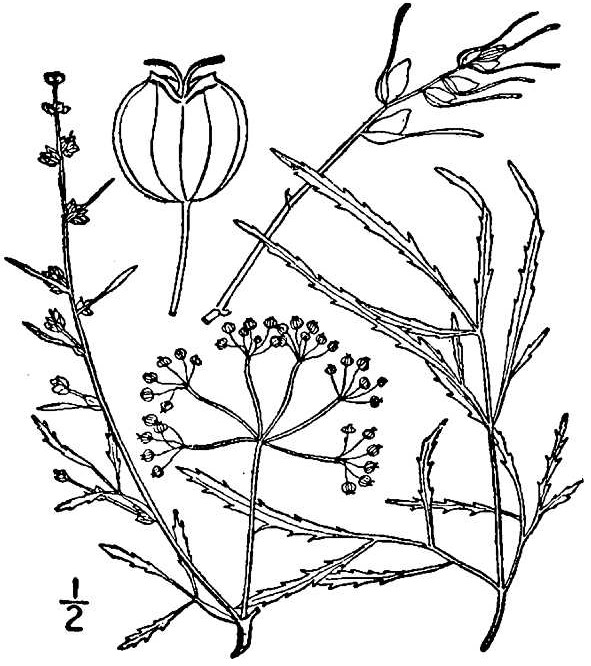

Bulb-bearing Water Hemlock (Cicuta bulbifera) drawing. (USDA-NRCS PLANTS Database / Britton, N.L., and A. Brown. 1913. An illustrated flora of the northern United States, Canada and the British Possessions. 3 vols. Charles Scribner's Sons, New York. Vol. 2: 658.)

Bulb-bearing Water Hemlock (Cicuta bulbifera). (By: National Museum of Natural History)

Bulb-bearing Water Hemlock (Cicuta bulbifera). (By: Rob Routledge CC BY-SA 3.0)

White & Red Baneberries

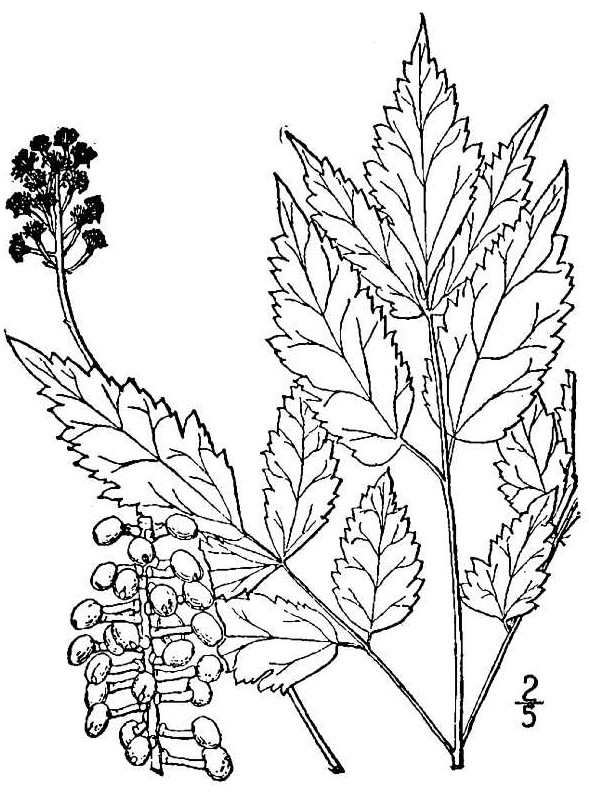

I've read reports that both the White and Red Baneberries (the White ones are commonly known as "Doll's-eyes") can cause blisters to form on the skin if the plant is touched. There is no question that both of these plants are very toxic to ingest as well - especially the fruit. Both are fairly common in Eastern North America. Best to know and avoid touching them.

White Baneberry or Doll's-eyes

White Baneberry or Doll's-eyes (Actaea pachypoda).

- Plant Size: Up to 60 cm (2 feet) tall

- Duration: Perennial

- Leaf Shape: Double or triple compound, Leaflet shape is highly variable

- Leaf Phyllotaxis (Arrangement) on branch: Leaves: Alternate. Leaflets: Opposite

- Leaf Size: 40 cm (16 inches) long by 30 cm (12 inches) wide

- Leaf Margin: Deep, coarsely Serrated (saw toothed edge)

- Leaf Notes: The leaflets can be lobed or without lobes.

- Flowers: An upright raceme of 10-28 bright white flowers.

- Fruit: Bright white berries with a black dot on red stems in clusters.

- Habitat: Woodlands in partial shade.

- Pictures on the web here (Google images) and here (Bing images).

- Interactive USDA distribution map and plant profile here.

- The Biota of North America Program (BONAP) distribution map here. BONAP map color key here.

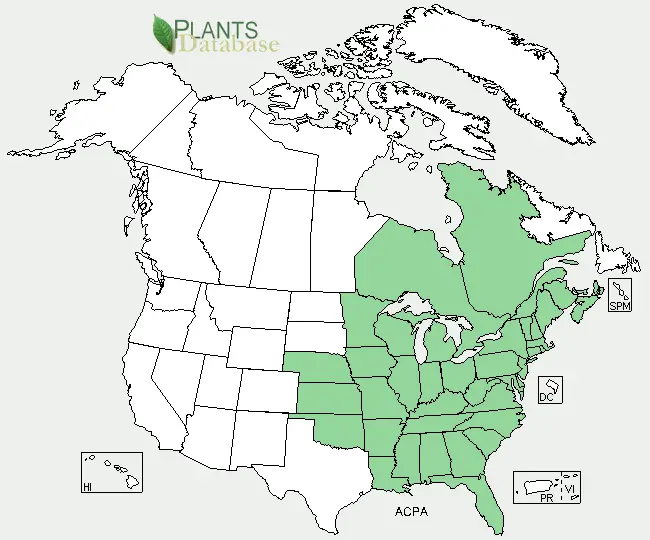

White Baneberry or Doll's-eyes (Actaea pachypoda) range. Distribution map courtesy of U. S. Department of Agriculture (USDA Natural Resources Service) and used in accordance with their policies.

White Baneberry or Doll's-eyes (Actaea pachypoda) drawing. (USDA-NRCS PLANTS Database / Britton, N.L., and A. Brown. 1913. An illustrated flora of the northern United States, Canada and the British Possessions. 3 vols. Charles Scribner's Sons, New York. Vol. 2: 90.)

White Baneberry or Doll's-eyes (Actaea pachypoda) leaves and flower. (By: D. Gordon E. Robertson CC BY-SA 3.0)

White Baneberry or Doll's-eyes (Actaea pachypoda) berries. See where the name "Doll's Eyes" comes from? (By: Meneerke bloem GNU Free Documentation License, Version 1.2)

White Baneberry or Doll's-eyes (Actaea pachypoda) in typical environment. (By: Cbaile19)

Red Baneberry

Red Baneberry (Actaea rubra). Very similar overall to the White Baneberry, but the fruit is bright red.

- Pictures on the web here (Google images) and here (Bing images).

- Interactive USDA distribution map and plant profile here.

- The Biota of North America Program (BONAP) distribution map here. BONAP map color key here.

Red Baneberry (Actaea rubra) range. Distribution map courtesy of U. S. Department of Agriculture (USDA Natural Resources Service) and used in accordance with their policies.

Red Baneberry (Actaea rubra) drawing. (USDA-NRCS PLANTS Database / Britton, N.L., and A. Brown. 1913. An illustrated flora of the northern United States, Canada and the British Possessions. 3 vols. Charles Scribner's Sons, New York. Vol. 2: 90.)

Red Baneberry (Actaea rubra) leaves and flower. (By: Anneli Salo CC BY-SA 3.0)

Red Baneberry (Actaea rubra) berries. (By: Walter Siegmund GNU Free Documentation License, Version 1.2)

A Special Threat to Pets and Farm Animals:

Some Foxtail Grasses in the (Hordeum) family can be a threat to animals, especially dogs. If you take your dog with you when out in grassy areas, I suggest to know what to look for and understand what can happen, to both prevent and be able to take quick action if your dog has made contact. Cats and other animals (common with cattle) can be affected, so know what you are dealing with if they are out where these grow.

There are many kinds, but they all look more or less like this. (By: Miwasatoshi GNU Free Documentation License, Version 1.2)

.jpg)

The dangerous part. (By: Matt Lavin Attribution 2.0 Generic

Search Wild Foods Home Garden & Nature's Restaurant Websites: